By Susan Kweskin, Ridgefield Historical Society Volunteer

“The town was very fortunate in having a gentleman of his attainments and culture settle among them.”

When I was a child, I used to hold my breath whenever we drove past a cemetery. These days, I find myself fascinated by old graveyards and the tales those old, crooked tombstones might conceal. For me, there is respite from a busy buzzing world, a connection with Ridgefield’s history, and a place to contemplate.

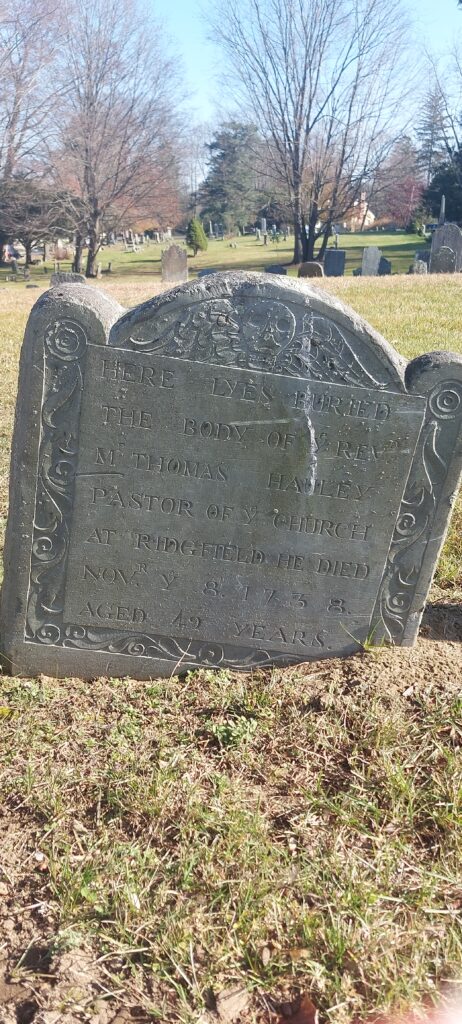

Not too long ago, on a warm and brilliantly sunny day, I walked with a friend in Olde Town cemetery. Susan* singled out one particular grave among the hundreds scattered nearby. It was the tomb in which the Reverend Tomas Hauley (occasionally spelled Hawley) was buried back in 1739. I think this means that the Reverend is still a local luminary – just as he was back in 1713 when he first came to live in a very young Ridgefield.

For someone who died so long ago, it’s amazing how much has been written about the man and the key roles he played in the settling of Ridgefield. As the town’s first tax collector and its first pastor, Thomas Hauley was the man about town, a leading citizen… the Rudy Marconi of his day.

Born in 1689 in Northampton, Massachusetts. Son of Joseph and Lydia. Grandson of Thomas of Derbyshire, England. Brother to 6. Father of 10. Gone at age 49. (His genealogy is exquisitely detailed by the Hawley Society, organized in 1923 in Bridgeport.

Why did this “frank, social, energetic” Harvard graduate (class of 1709) leave the relative safety of Boston and head for Ridgefield, which had only very recently been incorporated as a town? What propelled him to traverse the wilderness that was then Massachusetts when the risk of attack by “renegades” – human and animal – was very real and when trails and roads (if they existed) were poor, even in the best of weather?

Thomas must have envisioned a land of opportunity here. The brave settlers who had come only a few years before Thomas had settled their “plantations” in a land “rich with lumber, long ridges to build on, and abundant fish and game.” In 1708, permission had been granted to purchase land from Catoonah, “Sachem” of the Ramapoo Indians. Boundaries of that land which became Ridgfield (no “e” in Ridgefield in those early years) were vaguely marked by a rock on which stones had been laid, a giant white oak tree, a grassy pond (named Mamanasuag), and a mountain.

In 1709, a lottery was held to allocate “home-lotts” to the town’s first 25 settlers. That same year, the town appointed John Copp, a physician, as its first clerk and first schoolmaster. Thomas succeeded Copp in both roles in 1713. (In 1715, a full roster of officials was elected, including a drummer whose job was to “keep ye drum in good rigg.”)

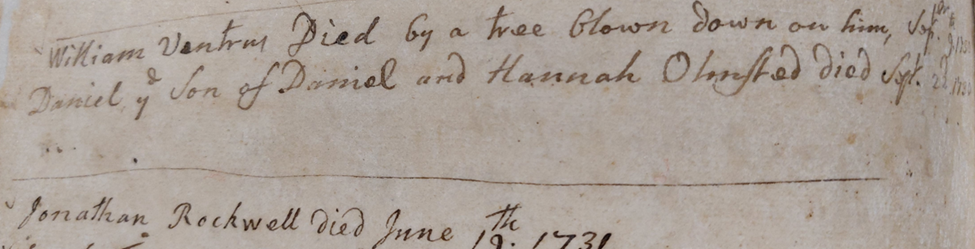

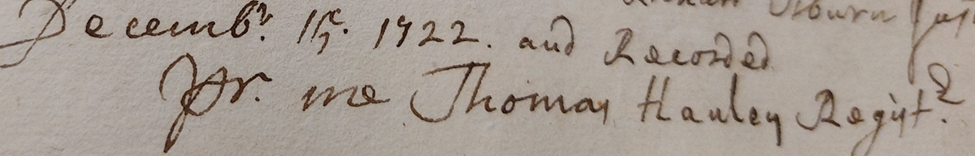

Every day except Sunday and until his untimely death, Thomas – quill in hand — recorded the goings on of Ridgefield…. children begotten, mishaps, accidents, marriages, wills, deaths.

His writings abide now in a handsome leather-bound volume (of the years 1709-1767) in Ridgefield’s town hall. If you take time to decipher his beautifully curlicued words (his handsome script “the admiration of his generation”) and witness his signature on page after page, it’s almost possible to feel his presence.

Thomas helped in the planning and building of Ridgefield’s first Church (the First Congregational, which still stands on Main St) and had a hand in determining who would sit in which pew every Sabbath. In 1715, after he had become the Church’s pastor (Ridgefield’s first), town elders granted him a plot of land — reserve #5 — that was to become “part of ye Minister’s house.” Young Thomas apparently wasn’t satisfied with the home, which also still stands on Main Street (#236), when it was finished in 1716. Not grand or formal enough for a man of such exacting and refined tastes! Thomas had to pay 10 pounds for his “own glass and nails” out of his “sallery” of 150 pounds or, alternatively, of 61 bushels of wheat to finish the job as he wanted it, which included the installation of windows (glass then a very rare and expensive thing) and even a double chimney.

Others less enterprising and ambitious than Thomas might have been overwhelmed by the intense challenges of settling here. The area may have been rich with potential, but it also teamed with snakes and wild animals—copperheads, rattlesnakes, bears, wolves, and bobcats – not to mention very rocky soil. The forests offered abundant wood for the building of homes, but the challenge of felling, moving, and hewing huge trees must have been daunting.

But “the men of Connecticut were trained in a school of hard experience. The town’s hillside farms and ‘gravlelly’ soil were not the nurseries of sluggards and idlers. A rigid economy was essential to bare substitene [sic]. Every man had an occupation and worked at it. It was no disgrace to work, but idleness was almost a crime. Mothers kept the homes and made the family clothing. The boys, when not in school, were doing chores or learning trades. The girls were teaching others and not ashamed to support themselves.”

Sundays offered a respite from the daily toil. The townsfolk who attended Thomas’ church could look forward to sitting still, sometimes for hours, in hand-hewn pews, whatever the temperature outside. Thomas’ wife and mother of his 10 children, Abigail Gold – daughter of the “distinguished Major Nathan Gold” of Fairfield – would have been seated in a special seat of honor.

Thomas’ church was not outfitted with a wood stove to warm the parishioners. The anti-stovites (not my word) believed that religious fervor should be enough to warm the soul. The stovites, not content with a warm soul, brought foot warmers filled with embers from home and tucked them underneath their many layers of clothing while listening to fire and brimstone.

Picture the Reverend on one of those freezing cold winter mornings, his breath and hands moving the frigid air, preaching about sin, temptation, damnation, condemnation, salvation. Listen up! Everlasting gruesome tortures awaited the sinner!

But you didn’t have to wait until after death to be on the receiving end of tortures so cruel they were practically medieval. Woe unto you if you broke the law – and there were many. Depending on your crime, you could be subject to public stripping and whipping: the number of “stripes” you got from the lash was directly proportional to the magnitude of your crime. (The public whipper was an important officer in those days. History records that in 1713, Richard Cooper was appointed to this post in New York City, which earned him a salary of 5 pounds.) Or you could face being dunked in a device in which you sat, hands tied and defenseless, while being repeatedly lowered under the water for prolonged periods. Stocks and pillories subjected the guilty to public humiliation. Or the dreaded treadmill or wooden horse (too awful to describe here) might await you.

Convicted of burglary or highway robbery? The penalty for a first-time offense was branding on the forehead with the letter B. Caught a second time? Whipping and branding. Third time? Death. If your offense was committed on the Sabbath, you’d get your ear cut off followed by the first two punishments.

The penalty for cursing God or religion? This and any other form of blasphemy was punishable by death.

Even law-abiding citizens lived by a stern code of conduct. Among them:

. No person worth less than 200 pounds could wear gold or silver lace or buttons, or bone lace costing more than 2 s per year, or silk hoods or scarves, under penalty of 10 s for each offense.

. Parents had to ensure their children read English, understood the basic rules of law, and were catechized weekly on religious principles. If a child was deemed rude or ignorant, he or she could be taken from the parents. And if a child should “smite” or curse a parent, the penalty could be death unless the parents had been “unchristianly negligent.”

. Any stubborn or rebellious son over age 16, “upon accusation his parents, should suffer death.”

Did the early Ridgefielders mete out some or any of these dire punishments? Unclear. But Ridgefield’s own whipping post stood at the corner of Main Street and Branchville Road — possibly in full view from Thomas’ house. Or perhaps Thomas’ parishioners could see it from their church window – a stark reminder of what an angry God or offended town magistrate could inflict.

Thomas’ entrepreneurial spirit was still evident as late as 1731, when the boundaries between New York and Connecticut were established. It was agreed that Connecticut would get Greenwich, Stamford, and Darien among other towns. (Bedford and Rye wanted to stick with Connecticut because of its lower taxes.) A whopping portion of lands newly incorporated into New York were divvied up and “patented” (purchased?) by Thomas and 23 of his associates. Those lots were highly desirable because they came with a guarantee of title. Thomas et al offered generous terms to prospective buyers. The debt could be paid in wheat, fat hens, or a few days of labor.

Thomas died from a lingering illness, for which he had been treated for nearly a year. It’s sobering to read his last will and testament, written in his own hand, in which he beseeches his God and Savior for mercy and apportions his worldly possessions to the wife and children he would soon leave behind. But his Church, his home, and his work, and even his tombstone still stand as witnesses to the Ridgefield he helped create.

*Thank you Susan Law of the Ridgefield Cemetery Committee.

**Thank you Betsy Reid and the Ridgefield Historical Society, the New Canaan Historical Society, Ridgefield Town Hall, and Google for providing the sources from which I cobbled this essay.