By Susan Kweskin

July 3, 1791. Captain Timothy Benedict is being laid to rest at the venerable age of 82. On this hot summer day, the Captain’s second wife, at least two of his surviving children, and members of Ridgefield’s young community are gathered in the brilliant sunshine, praying as they watch his coffin being lowered into the ground in Ridgebury cemetery.

The Captain is as old as Ridgefield — born here on November 15, 1709, the same year that local settlers have received permission from the General Assembly in New Haven to form the town.

Nearly 250 years after the Captain’s passing, I am standing in front of what I believe to be his tombstone. Only a few letters remain on this crumbling stone, but it stands next to Sarah Benedict’s – the Captain’s first wife. This disintegrating marker stands as mute witness to the man’s life and legacy, and it is among the oldest in this historic ground.

Details about the man’s life are sparse, but enough tantalizing clues remain. Timothy Benedict was one of 10 children born to Benjamin and Mary Platt Benedict. He married Sarah Smith when she was 25 in January 1734. Sarah, born in 1713 to Ebenezer and Sarah Smith, is one of the first non-natives born in Ridgefield.

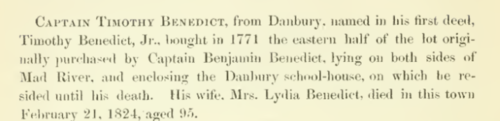

Sarah bears three children — Sarah, Abiah, and Timothy, the youngest of whom perishes “in ye 17th year of his age.” The Captain takes a second wife — Lydia — after Sarah’s passing when she was 53 in 1765. Lydia survives her husband by nearly a third of a century and dies at the mighty age of 95.

In 1744, Timothy goes to war. No clue as to why he decides to leave his home in Hemlock Hole (part of present-day Danbury just west of the Richter Park golf course) and family behind to fight. But he makes the arduous voyage – up to far Nova Scotia where he joins British forces in their latest war with France. This battle, known as King George’s war, is the third (of four) land grabs between the two superpowers…. a tug of war for domination, access to vast natural resources, and to defend against French expansion and raids.

Nearly 800 miles of unpaved and often mostly uncharted wilderness lie between Ridgefield and Nova Scotia. What few roads exist are little more than paths rudely cut through fields and woods. It would take weeks for Timothy and a cadre of other men from the various New England colonies to make this journey by land. Instead, Timothy likely makes the journey via ship up the east coast. Connecticut has contributed eight vessels to the battle and roughly 1100 men to help the British prevail.

Like most men of his time, Timothy would have been a skilled marksman. Armed with pistol and musket, he hunts game — deer, turkeys, rabbits, squirrels, raccoons, even bears – to help feed his growing family. At home in Ridgefield’s woods, he is accustomed to hot summers and bitterly cold winters and is thus well prepared to help fight the French up in Canada.

Timothy gets his chance for glory in 1745 when the British and colonial troops successfully lay siege to the French fortress of Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island. The fort controls access to the Gulf of St. Lawrence – a vital shipping route used to transport fur, fish, and other goods. Young Benedict is rewarded for his valor in this battle (presumably) and is named Captain, a commander of his own troops.

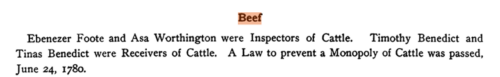

Our Captain returns to Ridgefield a military hero. There’s so much work to be done here, especially in Ridgebury where he and his family are early settlers. Here he is — a “receiver of cattle.” We can imagine him in this official capacity, making sure that the town’s beasts are well fed and watered, keeping vigil as each cow delivers her calf, and carefully recording each new birth.

[Knight EC, “New York in the Revolution” Albany NY, 1901]

Perhaps he is also one of the local fence viewers, charged with ensuring that livestock are securely penned and safely out of neighbors’ crop fields.

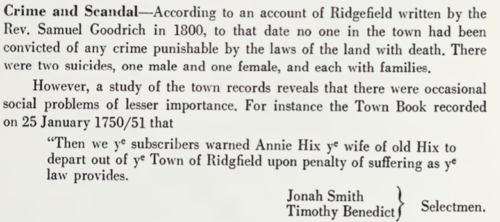

He also becomes a town selectman, responsible for local licensing, guarding the safety of townsfolk, and helping procure relief for the poor. (In Ridgefield, as in other towns at the time, selectmen could “warn out sick, weary, and hungry souls who tramped the roads into the town.”) In 1750, the Captain and fellow selectman Jonah Smith banish one “Annie Hix ye wife of old Hix…” from Ridgefield.

In 1775, in the immediate runup to the Revolution, our Captain joins a committee of a few dozen men charged with enforcing the trade boycott of British goods. (Seems an odd appointment for a man who’d fought with the British in Canada?) These men are tapped to “provide for ye families of such soldiers as shall enlist into the Continental Army, with necessaries, at the prices stated by law.”

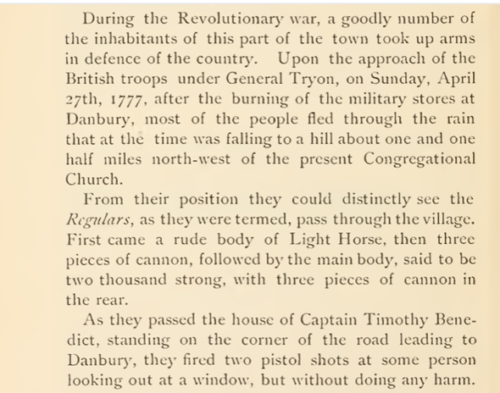

Too old to fight now against the British, Benedict (or someone in his family) is nevertheless the target of British bullets in the Battle of Ridgefield. On April 27, 1777, as English troops march through town after burning military supplies in Danbury, they pass the Captain’s house “standing on the corner of the road leading to Danbury.” (The box below offers details about the locale.) At least one of the “regular” soldiers fires off pistol shots at someone peering out Benedict’s window. Is it you they are aiming at, Captain? Regardless, the shots miss their target.

[Teller DW. The History of Ridgefield Connecticut. Danbury, pp 88; 1878.]

Later in his life, the Captain becomes a justice of the peace. The business of marrying of couples is among his responsibilities. This is not a job for clergy, and weddings do not take place in church. He will ensure that the betrothed have publicly announced their intention to marry via a “bann” issued at least three times. (This gives locals the chance to object to the wedding if they have a valid reason.) He will make sure that grooms bring some kind of property to the union and that brides bring their dowry. The colonists regard wedlock as an obligation and economic necessity: reproduction is the overriding goal. Being single is not a desirable option, and almost all adults marry or remarry.

But while Timothy Benedict is busy administering justice, protecting locals and their livestock, he is also the owner of at least two enslaved women. In his book Uncle Ned’s Mountain, Jack Sanders provides these details of the two: Dorcas, “ye negro woman servant of Timothy Benedict, died January 10, 1760 and Phyllis who was “admitted to the Ridgebury Congregational Church, Oct 3, 1790 Lord’s Day.

War veteran, justice of the peace, protector of townsfolk… slave owner. As they say, the past is a foreign country.

Might the dead somehow know that someone is thinking about them? If so, Captain Timothy Benedict’s ears must be ringing.

Susan Kweskin is a member of Ridgefield’s Graveyard Restoration Committee.