by Susan Kweskin

Dead is dead, but are people somehow less dead because someone is again thinking about them?*

Old graveyards hide hundreds of fascinating stories. Walk around slowly and take time to decipher some of the fading tombstone etchings that record names and dates of those who once lived here. If you’re looking for a connection to the past, this is a good place to start.

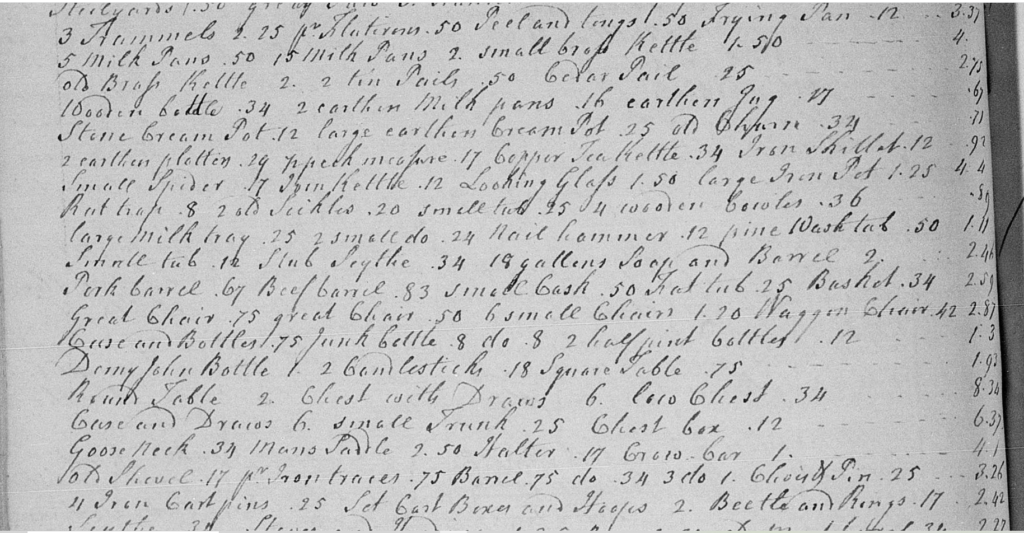

It takes some digital digging to exhume details about the life of someone long deceased. But it’s astonishing how much information you can unearth about someone who lived centuries before computers. If you take time to decode the beautifully curlicued handwriting recorded more than 200 years ago in town records, you can find out how much land someone once farmed, how many children they had, which survived them, what they wore, how many cows they milked, and (if they were rich) the names of the books they once owned.

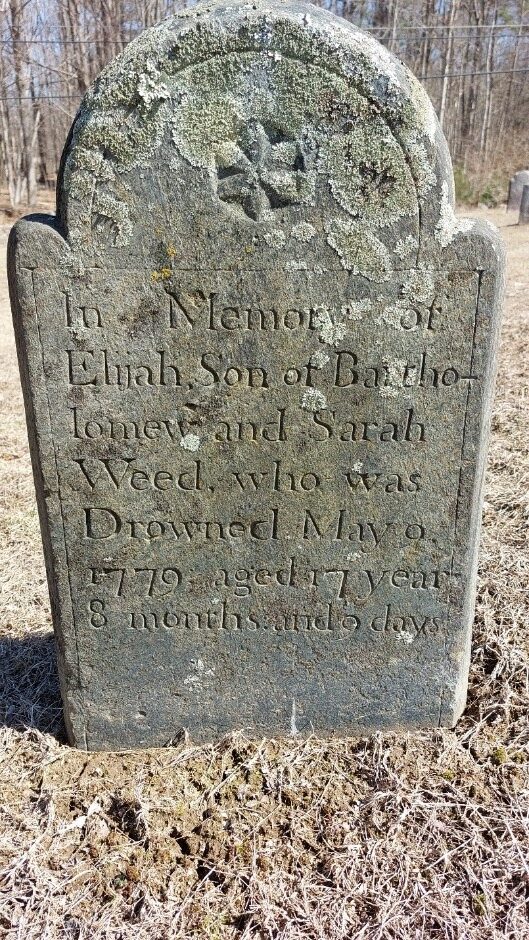

Take the arresting tombstone of young Elijah Weed, buried now for nearly 250 years in the Ridgebury Road Cemetery, just down the way from the church his family once attended. Elijah drowned on May 9, 1779 at age 17, his headstone records. But his brief life must have teamed with adventure.

The son of a prosperous farmer (Bartholomew, born in 1730) and his wife (Sarah Benedict, born in 1735), Elijah and his siblings – he was one of five — – grew up in Ridgebury. His parents owned at least 100 acres of land, a house, and a barn. A meticulously recorded inventory details the Weed’s worldly goods — such things as leather straps (valued at 34 cents), a tankard (25 cents), 15 milk pans (2.00), 2 old sickles (20 cents), a bread tray (17 cents), a pair of blue seamed stockings (75 cents), white woolen sheets ($3.00) and “rye on the ground on the mountain” (7.00). The entire estate was valued at $2,961.56.

Bartholomew and Sarah outlived Elijah. They also outlived Joseph, their youngest, who never saw his sixth birthday. The graves of both parents flank their sons.

A sister, also Sarah, died in 1782 at age 26 during one of New England’s periodic smallpox epidemics. Sarah’s death certificate records that she “died of smallpox by inoculation.” Vaccination, then in its infancy, was widely mistrusted. No small wonder. Material collected from the pox of an infected person was scratched into the skin of an uninfected person to elicit a mild infection. Because the dosage of inoculate was imprecise, about 2% of those who were vaccinated with live pox died of the disease. But 14% of those who weren’t vaccinated succumbed to infection. You took your chances.

Two surviving siblings — sister Chloe and brother Timothy – lived to inherit the Weed estate. Thirty acres of Weed land was sold to Timothy Keeler, himself a revolutionary war veteran, who died in 1799 at age 77 and who is buried not far away in Olde Town cemetery.

Young Elijah Weed joined the colonial army on May 8, 1777 for a term of enlistment recorded as “during the war,” and he was discharged in late 1778. It seems likely that he joined in the immediate aftermath of the Battle of Ridgefield on April 27, 1777. He served in Colonel Philip B. Bradley’s regiment and earned 2 pounds a month for his service.

Private Weed – a soldier fighting the mighty British empire at the tender age of 15? Was he trained to fight? What weapons did he carry? And for that matter, what was he like? What made him laugh? Perhaps the answers lie in letters or records I’ve yet to tap.

And where did Elijah drown so soon after soldiering? I found no clues. But I believe the words that follow (not mine) address something far more profound.

You were a presence full of light upon this earth and I am a witness to your life and to its worth**

With thanks to Dana Wickware* and The Mountain Goats**