Written by Susan Kweskin

It’s early morning on the Taylor farm in Ridgefield. December, 1787.

The sun that rose barely an hour ago has cleared out the clouds that threatened snow today. But in her kitchen, 44-year-old Abigail Taylor isn’t thinking about the weather. She has already milked the cows, gathered eggs, made breakfast, and is now working over the hearth in her kitchen. Water is bubbling in an iron kettle that hangs over glowing coals in her fireplace. She has chosen a handful of her best recently picked apples from an overflowing basket in the root cellar and has strung glistening slices of the fruit with a length of twine that hangs over the relative warmth of the fireplace mantle. The desiccated slices will keep all the long winter that is soon to come. Come February or March, when the family has eaten up all the stored apples, Abigail will soak her dried apple slices and use them in a pie.

Abigail turns her thoughts to the many tasks that lie ahead today. But she feels unwell, and the chill air today isn’t making her feel any better. It hurts her to breathe and there’s an aching in her chest. She’d love to rest for a little while, but it’s just not an option.

She turns her attention to the bread she must make this morning– enough to last for a week. The corn and rye the family planted this past spring had flourished. The grain she had had ground will make hearty loaves. (A mill on Mamanasco Lake was operating for much of her adult life.) She sets an empty bowl on her table and pours in water, salt, sugar, and handfuls of rye flour and cornmeal. To this slurry, she adds a small chunk of the yeast cake she made this summer – the leavening agent made from wild yeast and bacteria in the air combined with the sugar water she left out for a few days in her kitchen. As she kneads the thirsty dough, adding water as she goes, she feels so weary. The kneading takes muscle – she repeatedly throws the heavy mass of dough against a board for good mixing. When it is finally the right consistency, she plops it into a bowl where it will be left to rise. Unclear how long this will take: rising time is a function of warmth and humidity, among other things she can’t control. It may take hours – or sometimes even days. Later, she will prepare her oven for baking. To do this, she will add burning embers from her fireplace to her brick bread oven. When the embers cool, she will sweep the oven clean. The bricks in that oven will be hot enough to cook the bread and any pies she might be thinking of making.

How daunting the act of bread baking would be to a modern cook!

Abigail forces herself to work on the main meal of the day, which will be served mid-day. Pork – from the 500 pound fat hog her family has raised and butchered – is again on the menu. Some farmers in New England have begun to export preserved pork to England, where it is considered a delicacy. But the Taylor family isn’t in the export business. Every single morsel of their recently slaughtered pig will be put to use. The animal’s fat has been rendered, meat cured in salt…ears, feet, snout. Abigail has already soaked several slices of the salt-cured meat and now begins to fry it with her apple slices and some potato. She adds cloves and a dash of nutmeg to the dish for extra tastiness.

Mid-day meal now over, Abigail considers the many additional tasks that must be attended to. Several chickens running around outside are to be slaughtered. These are small birds – most weighing less than 5 pounds – and don’t provide much meat. But the roasted fowl will be a special treat and a tasty break from the usual. Butchering will be no easy task. Once captured, beheaded, and gutted (by hand), Abigail will soak the little carcasses to speed the job of plucking the feathers. Even so, it’ll take a precious hour or two to denude the beasts, whose feathers will be collected and stuffed into pillows and quilts.

And then there’s sewing, food to be canned and preserved, candles and soap to be made, children to supervise. The list is long. Abigail tries to keep warm by remaining in constant motion. Energetic industry is key. No easy thing in a cold house when her chest aches with every breath.

December 25th is fast approaching, but Abigail takes little notice and plans no special preparations. Holidays are generally spurned in Puritan New England, and festivities of any kind are actively discouraged. Holidays, it is believed, are created by humans, not by God. To mark out a single day as special is to disparage other days, every one of which is holy. An insult to the Lord.

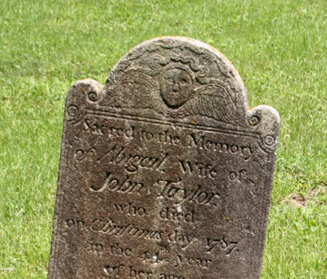

But despite the holiday prohibitions, Abigail does indeed mark December 25, 1787. This will be the day of her death. There will be no celebration for the Taylors this year– no visiting with neighbors or singing or baking Christmas cookies. Instead, there will be a quiet burial in nearby Ridgebury cemetery.

Abigail Mygatt Taylor, born in 1744 in “Danbury, Fairfield, Connecticut, British Colonial America” to Joseph Mygatt and Elizabeth Starr, lived in Ridgefield and died here 237 years ago this Christmas. And though no records detail how she spent her days, our fictional account of her adult life is probably not far off the mark. Her tombstone records that she passed on December 25, 1787, at age 44. Cause unknown. She lies entombed next to her husband John Taylor (1743-1816), whom she married on December 16, 1762. She bore at least 3 children: daughter Hannah and son Najah (both died in 1860), and also John, born in 1779, who died on an undisclosed date.

What specifics do we know about the Taylors? Good question. Given the wealth of detailed information about early Ridgefield – in large part thanks to Jack Sanders – it’s surprising that I found so few clues about this one family. There are other Taylors – including Joseph Taylor who ran a flour mill and a Davis Taylor who was the mill’s previous owner. There are even a number of references to Elizabeth Taylor, who was a guest in Ridgefield centuries later.

Wrong Taylors.

Between birth, marriage, parenthood, and the grave, no details were found in any of the sources I reviewed …. where the couple lived, whether John ever remarried and had more children, and the cause of their deaths. John Taylor’s name is not listed among those who inherited or purchased one of the plots of land given to the original 25 families who settled here in 1709. His occupation is unknown: his name does not appear among the craftsmen of early Ridgefield – he was not a miller, tailor, blacksmith, silversmith, hatter, weaver, cooper, harness or coach-maker, or a carpenter. He is not listed as a veteran of the Revolutionary war. No listing in the church rosters of the day. No obituary for either partner on the Historical Society’s website. Almost a ghost.

But we do know that John Taylor was born in 1743 in Danbury, that he died in Stamford in 1816, and that he was interred next to his wife in Ridgebury cemetery. He was one of three sons born to Theophilus Taylor (1715-1781) and Hannah Dibble (1721-1804). A younger brother, also named Theophilus (1749-1824) is buried somewhere in Ridgebury cemetery. A second brother named Jeremiah (1758-1850) also appears in John’s family tree, but kinship seems unlikely since Jeremiah’s birthplace is listed as North Carolina or Georgia.

There’s just one entry about our John Taylor: in 1810 (long after Abigail’s demise) he purchased eight acres of land somewhere east of Ridgebury Road.

We also know that in the New England of 1776 when Abigail and John were in their prime, boycotts of any celebration – including Christmas — were widespread. December 25? Just another day. Congress and courts of law convened on Christmas day, unless it fell on the Sabbath, and business went on as usual. In fact, Christmas celebrations would not exist in the new world – at least as we know them – until the mid-1800s.

Given this backdrop, it seems ironic that the epitaph on Abigail’s tombstone singles out Christmas day as her dying day…a nod to the special holiday she herself may never have celebrated. There’s something comforting about the way her headstone leans over toward her husband’s.

It seems fitting that we remember and honor Abigail this Christmas, and the husband who lies next to her.

PS: For more about 18th century New England Christmas, watch this youtube video. You’ll be treated to a recipe for coriander Christmas cookies from 1796.