Authored by Susan Kweskin

It’s January 6, 2024. Dark. The meteorologists have been having a field day with dire predictions about a gigantic snowstorm that will begin to drop up to 8 inches of snow on Ridgefield any minute now.

It’s so cold out there tonight! I’ve turned the heat way up to 69. The blower in the fireplace keeps the living room cozy and toasty. There’s dinner in the oven. The house is ablaze with light and warmth – and a hot shower and Netflix await.

Tonight in particular, I am savoring every single one of our 21st century comforts.

How different things must have been on a night like this when Rachel Wallace Dauchy lived here in Ridgefield almost 300 years ago. Her home. . . so silent, so cold . . . darkness hardly punctured by the light of an oil lamp . . . frigid water outside in the well, fire dying downstairs, family huddling together under the covers for warmth.

So much for thinking I was born in the wrong century.

Rachel was born in Ridgefield in 1711 to James and Mary Wallace. Her dad, born in 1674, hailed from Scotland. Her mom was born in Norwalk in 1682. Rachel’s older brother John, born in 1708, apparently died in very old age in 1811. Her younger brother, James (1713-1782) served as a Captain in the Revolutionary War.

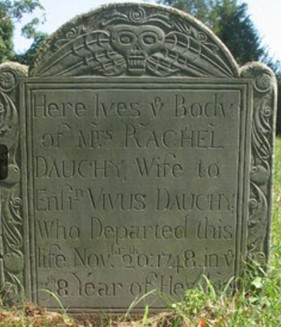

Rachel was 38 at her death. She lies under this tombstone in Olde Town cemetery.

In a Facebook post, Jack Sanders wrote of Rachel’s tombstone: “Although it is more than 270 years old, the face is as crisp as the day it was carved. The stone has been so durable that you can still see not only the horizontal scores the carver used to keep his lettering straight and correctly sized, but also a fine vertical line he employed to tell himself where the exact middle of the stone’s face was.”

Details about her life are scarce. But it’s not hard to imagine how she filled her days. In Rachel’s day (and maybe in our own), no household could function for long without a matriarch. Bad enough that a patriarch should become incapacitated – an unwell mother “meant that routines of the household would begin to unravel….when household chores could not brook the interruption.”

For the women of colonial Connecticut, household chores meant toiling from dawn (or earlier) to dark. No stores to buy groceries or clothing or medicine for these settlers. Industry was the order of the day, spent cooking over an open fire and baking, preserving food, churning butter, making cheese, spinning thread, sewing, weaving, milking, slaughtering, and preserving meat, making candles and soap, bearing and raising multiple children, and educating them.

And there were so many children to bear and raise! Big families ruled: broods of even a dozen children weren’t uncommon. Rachel labored 7 times, each time keenly aware that her chances of dying during and after delivery were high. Exhaustion, dehydration, infection, hemorrhage, convulsions took the lives of roughly one in 8 multiparous women. No surprise then that many colonial New Englanders feared pregnancy. Childbirth was regarded as “The dreaded operation,” “the greatest of earthly miserys,” and an “evil hour I loock forward to with dread.”

Superstitions regarding childbirth abounded. A newborn might be disfigured if its mother happened to look at a “horrible spectre” or was startled by a loud noise. A harelip? Mom must have encountered a hare. Child a “lunatic”? Sleepwaker? Mother must have looked at the moon. And what of mom’s “ungratified longings”? Miscarriage or some mark on the child’s body might be the consequence.

Advanced pregnancy? No excuse for a nap! Work stopped only at the point of the onset of labor, at which point female relatives, neighbors, friends, and/or a midwife were summoned to attend. Hard work – even until the start of contractions – was believed to make for an easier labor.

But pain during labor was viewed as God’s punishment for Eve’s original sin. (Did an easy labor mean escaping God’s wrath?) No anesthetics for a laboring woman – except perhaps alcohol. Women were forewarned to be patient, to arm themselves with prayer, and to try to refrain from “those dreadful groans and cries which do so much to discourage their friends and relations that are near them.”

Rachel’s fears about her own demise during childbirth were surely compounded by worry about her newborn’s chances of survival. Death took between 1 and 3 children in 5 before their fifth birthday depending on where you lived. Puritan Minister and author Cotton Mather, who died in 1728, lost 8 of his 15 children before they were 2. Mather wrote: “We have our children taken from us…the desire of our eyes taken away with a stroke!”

What claimed Rachel’s life on November 20, 1748? It wasn’t childbirth: her youngest, Nathan, was born on February 9, 1747 – almost two full years before her passing.

Did an infection take her? It’s possible: epidemics routinely savaged the colonies. The colonists who came to New England, like the slaves who were carried here in ships of unimaginable squalor, were carriers and victims of a panoply of plagues: smallpox, malaria, dysentery, yellow fever, diphtheria, scarlet fever, influenza, pleurisy, colds, whooping cough, mumps, measles, typhus, typhoid fever, hookworms and parasites, syphilis and other sexually transmitted diseases.

But none of Rachel’s family fell ill or died around the time she did.

Did the cold get to her?

Rachel’s life story can’t be told without telling of Captain Vivus Dauchy, the man she married on November 28, 1732. There’s more to be gleaned about Vivus’ life than Rachel’s. Several years her senior (he was born in 1707), Vivus and his parents had fled religious persecution of Huguenots in La Rochelle, France. They sailed the Atlantic, landed in New Rochelle, New York, and settled in Ridgefield in 1725 – itself no bastion of religious tolerance.

Vivus purchased land near the center of Ridgefield in 1729. In 1741, he purchased a “home lott” on Town Street — now Main Street — from what some sources say was his father-in-law, David Scott. He built a home on that choice piece of property that somehow connected to Scott’s home.

Scott’s original saltbox home – now (appropriately) named the David Scott house — still stands. It was moved from the southwest corner of Catoonah Street in 1922 and then again in 1999 to Sunset Lane, where it houses the Ridgefield Historical Society. The “beams in the cellar are all hand-hewn and drop-morticed” according to one report, and the floors “covered with oak board of great width.”

Land wasn’t all that Scott sold to Vivus. He also sold two slaves to the Dauchys. Land records show that in 1740, Vivus purchased “a certain Negro woman named Dinah, and a Negro boy, named Peter.”

While hunting for more details, I found a newspaper clipping from June 10, 1953 from Winona, Minnesota that begins “Oh, those good old days!” The author tells of coming across an old deed dated February 13, 1740. (Incidentally, that same deed appeared in four other newspapers on the same day in 1953 – in Pennsylvania, New Mexico,

Indiana, and Kentucky.)

Scott’s personal estate also included a “Negro girl named Ann,” valued at 37 1/2 pounds.

Vivus knew what it was like to be persecuted. Like others of his faith, he had left France behind to find religious freedom in the new world. Yet here in that new world, he purchased human beings and stripped them of all freedoms – a practice common and rarely examined in 18th century New England.

Still, he came to be regarded as a “prominent Ridgefield patriot.”

Rachel lived with and presumably worked side-by-side with Dinah and Peter for the last 8 years of her life. What kind of relationship did they have? Did she question the arrangement or simply see it as part of the accepted social order? Perhaps she voiced her objections? Threatened divorce?

The latter seems unlikely for a number of reasons. Rachel, like most women of her time, lost property rights in marriage, and Vivus would have been granted custody of their children. Petitions for divorce or separation weren’t rare, but they were often denied. For the unhappily married, desertion was “the easiest method to quit a miserable situation.” Desertion with 7 children? Not, I think, an option for Rachel.

Vivus remarried again – and then again – after Rachel’s passing. He fathered one more child with Hannah Sherwood (wife #2) and five more (the last child when he was nearly 60) with Mary Keeler Olmstead (wife #3). Total children? I count 12 in the record below, but I calculate 13 in all.

As the primary parent (according to the law), Vivus would have been busy teaching his children to write and to farm, placing them in a “lawful calling” or occupation, leading household prayer, meting out punishment for insubordinate or unruly behavior, and granting consent to marry.

He lived to the grand old age of 88 and died on December 16, 1795. Here he lies, in Titicus cemetery. But he’s not been forgotten: in 2022, two of his great-great-great grandchildren came knocking at the door of the Historical Society, looking – just like I did – for insights into the life of their long-gone ancestor.

I’ll end Rachel’s tale of toil where it started: a bitter cold Ridgefield night. Would Rachel have wanted to swap places with us? What would she make of a life of electricity and electronics? Would she have gained the same satisfaction, joy, even happiness she surely did by doing it all with her own two hands? I wonder.

A special thank you to Betsy Reid and Sally Sanders of the Ridgefield Historical Society for their comments and suggestions on this essay.