Architectural Glossary

While many buildings exhibit characteristics of defined historic architectural styles (e.g., Greek Revival, Queen Anne, Colonial Revival), others were simply identified as “vernacular,” meaning a structure without any specific stylistic attributes, though still typical of its time and place.

Some terms like “Victorian” and “Colonial” denote a period, not a style. For example, the term “Victorian architecture” actually refers to styles that emerged in the period between 1830 and 1910, during the reign of Queen Victoria. The Victorian era spawned several well-known styles, including Gothic Revival, Italianate, Second Empire, Queen Anne, Stick style, Romanesque, and Shingle style.” Similarly, “Colonial” is generally a period and a “Center Chimney Colonial” is more thank like a Georgian style building.

The following descriptions, in chronological order, are aligned with the terminology contained in Virginia and Lee McAlester’s Field Guide to American Houses (New York, 1984), and Steven Phillips’ Old House Dictionary (Washington, D.C., 1992). Explanations of the most frequently used stylistically terms are as follows.

Prepared by Phil Esser.

New England Farmhouse (1700-1790)

New England Farmhouses, occasionally with Georgian or Federal decorative details, are usually rectangular, range from one-and-a-half to two-and-a-half stories in height, with central entryways situated on the long elevation. Originally sheathed with narrow clapboards, they contain large centrally placed chimneys and windows of small-pane sash, often of twelve-over-twelve or six-over-nine configuration, and placed in a symmetrical three-bay or five-bay façade. Vernacular variations persisted through more rural areas through the nineteenth century.

Cape Cod (1700-1850)

These small, single-story houses with gable roofs, constituted much of New England’s housing stock in the colonial and early national eras. They usually incorporate a central entry and central chimney in a balanced five-bay façade. “Half houses” and “three-quarter” houses present unbalanced three- and four-bay facades. Sheathing consists of clapboards or shingles, depending upon location. Earlier examples utilize few decorative details, while later Capes incorporate a variety of Federal or Greek Revival motifs. Throughout the eighteenth century, Capes with low eaves and short eight-foot corner posts predominated. In the nineteenth century many builders utilized twelve-foot corner posts, which raised the eaves and provided more usable space beneath the roof. They are sometimes referred to as “raised Capes.”

Georgian (1700-1780)

Georgian buildings range from simple farmhouses to high-style residential types. Typically one to two bays deep, the houses are identified mostly through their symmetrical facades. With centrally-placed, paneled entry doors, the doors are often surmounted by a pediment or elaborate crown, or entablature. A horizontal band of small windows are often placed under the crown. Window placement is symmetrical, being three to five bays wide, and usually consists of double-hung sash with small panes (if original). With large center chimneys, the roofs are mostly gabled though some are gambrel type.

Federal (1790-1830)

Federal-period buildings are characterized by overall symmetry and the lightness and classical nature of their decorative details. The entranceway, considered the signature of a stand-alone Federal building, is generally located on the long elevation of the house, which faces the road, rather than the gable end. Entries often contain six-panel doors flanked by leaded sidelights, surmounted by a semicircular or elliptical fanlight. Cornices may be decorated with swags, dentils, and modillions, more finely detailed than their high-style Georgian predecessors, utilizing Roman classicism made popular by the Adam brothers in England. Windows often incorporate molded entablatures.

Greek Revival (1820-1860)

The Greek Revival style emerged as the dominant American architectural expression in the second quarter of the nineteenth century. It proved very popular for churches, public and commercial sites, and mansions, as well as humbler domestic and commercial structures, many of which were built as loose variations of ancient pedimented temple designs. Typical examples are placed with their gable ends oriented to the street and are characterized by broad, flat surfaces, low-pitched roofs, classical columns or pilasters, pedimented gables, wide frieze boards, a prominent cornice, and classically inspired doorways. Fenestration commonly utilizes six-over-six double-hung sash.

Gothic Revival (1840-1880)

The Gothic Revival was based on medieval English forms and fashionable in England before it appeared in America. The earliest of our Victorian domestic forms, identifying features of the style include steeply pitched roofs, usually with steep cross gables commonly decorated with ornate vergeboards; wall surfaces and windows that extend uninterrupted into the gables; one-story porches, and; Gothic-inspired window heads. Carpenter Gothic, a variation on the style, is applied to more vernacular types where Gothic elements are applied by craftsman.

Italianate (1840-1885)

Like the Gothic Revival, the Italianate Style has its roots in England’s Picturesque Movement. Most recognizable to the style are the vertically-oriented form with the signature tower or rooftop lantern, or cupola. Identifying features are heavy, ornate, door and window moldings as well as rounded window tops and segmented door crowns. Consistent with the elaboration of moldings are generally wider roof eaves supported by heavily bracketed cornices. For the first time, large panes of glass could be manufactured which could infill an entire sash.

Stick Style (1860-ca. 1890)

The style is defined mostly by decorative detailing. It is a transitional style which bridges the Gothic Revival with the subsequent Queen Anne. The style integrates the decorative elements into the wall surfaces as opposed to applied ornamentation. Noted for its efforts to honestly express the underlying structural elements the details are in fact, surface decorations. Identifying features include decorative trusses in the gable ends; overhanging eaves; siding applied in various patterns and directions, and; corner boards. As a popular style, the details were often applied to preexisting farmhouses and do not represent high-style examples.

Queen Anne (1880-1910)

The style was dominant, particularly in the northeastern states from about 1880-1900. The name was coined by 19th century English architects led by Richard Norman Shaw. Based primarily on Elizabethan and Jacobean precedents, the American style is identified by irregular massing with a dominant front-facing gable. Numerous sub-types evolved, the most common being the “spindlework” type with ornate detailing and the later, “free-classic” type which utilized classical-inspired details.

Colonial Revival (1880-1940)

The Colonial Revival style was the most popular form of architectural expression in the first half of the twentieth century. Houses of this type combine a variety of historical and contemporary elements (mostly Georgian, Federal, and Dutch Colonial) to recreate the “feel” of earlier American buildings. Individual elements, however, are often exaggerated. Front entries are emphasized often with classical-inspired porticos. Palladian windows and other classical details from a wide range of Greek, Roman and Renaissance precedents are frequently incorporated into gables and facades. Windows are normally arranged symmetrically and contain double-hung, multi-pane sash.

Classical Revival (1880-1940)

The Classical Revival can be differentiated from its Georgian and Federal cousins in that the execution is typically more academically rigid, or formal, in execution. Based in classical Roman precedents, It is also typified by a two-story front porch supported by classical columns and either pedimented or crowned with a balustrade, or railing. The formal entry door is typically crowned by an elaborate pediment, often with a high-style, curvilinear broken pediment, sometimes referred to as a “swan’s neck”.

Tudor Revival (1890-1940)

Based on English Medieval precedents, the style is a distinctly Americanized expression, later borrowing elements from the Arts and Crafts Movement. The building forms are not rigid and can have varied roof lines, but the forward-facing, often steep, gable form is most prevalent in the style. The most predominant identifying feature is the fake half-timbering elements that dramatically contrast with the light stucco wall surfaces; the timbering element can vary widely. Other typical stylistic elements include vertically-oriented, diamond-pane casement windows, steep gable elements, decorative brickwork on chimneys, and in high-style examples, oriel windows.

Arts & Crafts (Commonly known as “Craftsman”) (1910-1930)

The style, which has its roots in England, was an architectural outgrowth of the late nineteenth century American Arts And Crafts movement, especially the work of California architects Charles and Henry Greene and advocate Gustave Stickley with his publication, The Craftsman. Bungalows executed in this style are usually one-and-a-half stories high, set on cobblestone foundations, with low-pitched roofs, wide overhanging eaves, exposed rafter tails, and prominent eave brackets. Full or partial front porches are supported by stout, often tapered (battered) square half-columns. Continuous shed dormers are frequently located above the front porch. Craftsman detailing was also adapted to larger two and three-story buildings, especially the porch and eave details.

Balustrade

Balustrade

A railing consisting of a row of balusters or spindles supporting a rail.

Bay Window

Bay Window

A projecting bay which protrudes from the surface of a wall creating a small, nook-like interior space that is lit on all of its sides by windows.

Bracket

Bracket

A projection from a vertical surface that provides structural and/or visual support for overhanging elements such as cornices, balconies, and eaves.

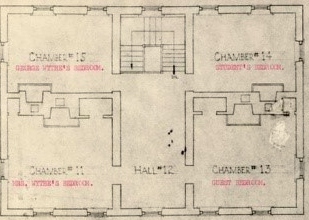

Center Hall

Center Hall

A passageway that cuts through the center of a building, from front to back, and off of which rooms open to the sides.

Coffer

Coffer

A sunken paneling in a ceiling, including the interior surfaces of domes and vaults.

Columns

Columns

A supporting pillar consisting of a base, a cylindrical shaft, and a capital on top of the shaft. Columns may be plain or ornamental.

Cornice

Cornice

A crowning projection at a roof line, often with molding or other classical detail.

Cupola

Cupola

A small dome, or hexagonal or octagonal tower, located at the top of a building. A cupola is sometimes topped with a lantern. A belvedere is a square-shaped cupola.

Dentil Molding

Dentil Molding

Small rectangular blocks that, when placed together in a row abutting a molding, suggest a row of teeth.

Dormer

Dormer

A perpendicular window located in a sloping roof; triangular walls join the window to the roof. Dormer windows are sometimes crowned with pediments, and they often light attic sleeping rooms; “dormer” derives from “dormir,” French for “to sleep.”

Eave

Eave

The projecting edge of a roof that overhangs an exterior wall to protect it from the rain.

Entablature

Entablature

The superstructure of moldings and bands which lies horizontally above columns, resting on their capitals.

Façade

Façade

An exterior wall, or face, of a building. The front facade of a building contains the building’s main entrance, the rear facade is the building’s rear exterior wall, and the side facades are a building’s side exterior walls.

Finial

Finial

A distinctive ornament at the apex of a roof, pinnacle, canopy, or similar structure in a building.

Frieze

Frieze

A band of richly sculpted ornamentation on a building.

Gable Roof

Gable Roof

A roof with two slopes – front and rear– joining at a single ridge line parallel to the entrance façade.

Gambrel Roof

Gambrel Roof

A ridged roof with two slopes at each side, the lower slopes being steeper than the upper slopes.

Half-Timbering

Half-Timbering

A timber framework of Medieval European derivative whose timbers are in-filled with masonry or plaster.

Hipped Roof

Hipped Roof

A roof with four sloped sides. The sides meet at a ridge at the center of the roof. Two of the sides are trapezoidal in shape, while the remaining two sides are triangular, and thus meet the ridge at its end-points.

Keystone Window Ornament

Keystone Window Ornament

A central or full-width keystone element placed above a window frame.

Mansard Roof

Mansard Roof

A four-sided hipped roof featuring two slopes on each side, the lower slopes being very steep, almost vertical, and the upper slopes sometimes being so horizontal that they are not visible from the ground. The Mansard roof was named after the French 17th-century architect Francois Mansart (1598-1666), who popularized the form.

Oriel Window

Oriel Window

A projecting window of an upper floor, supported from below by a bracket.

Palladian Window

Palladian Window

An arched window immediately flanked by two smaller, non-arched windows, popularized by Andrea Palladio in northern Italy in the 16th century, and frequently deployed by American architects working in the American Georgian and American Palladian styles in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Pediment

Pediment

A decorative triangular piece situated over a portico, door, window, fireplace, etc. The space inside the triangular piece is called the “tympanum,” and is often decorated.

Portico

Portico

An entrance porch with columns or pilasters and a roof, and often crowned by a triangular pediment.

Ridgeline

Ridgeline

The horizontal intersection of two roof slopes at the top of a roof. Also called a Roof Ridge.

Roof Ridge

Roof Ridge

The horizontal intersection of two roof slopes at the top of a roof. Also called a Ridgeline.

Turret

Turret

A small tower that pierces a roofline. A turret is usually cylindrical, and is topped by a conical roof.

Veranda

Veranda

An open, roofed porch, usually enclosed on the outside by a railing or balustrade, and often wrapping around two or more (or all of the) sides of a building.