For where God built a church, there the Devil would also build a chapel. Martin Luther

Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live. Exodus

It’s an early Sunday morning in June, 1979 in Ridgefield. A local policeman is on a routine patrol. As the young man drives slowly through a heavily wooded area of town, he suddenly hears unusual sounds coming from behind the trees. He stops his car and tunes in to an ominous, rhythmic sound of voices chanting in unison. The officer cannot make out the words. He makes a quick call to police headquarters before he walks into the woods towards the sounds. He must be surprised by what he witnesses: a small group of people all wearing black hoods. Four of these hooded apparitions immediately set upon the lone officer, beating him. Despite multiple wounds and a head injury (for which he is later hospitalized), the policeman fights back and manages to fend off the attack by spraying Mace. Though wounded, he races back to his car and turns on his siren as his attackers flee.

As Jack Sanders writes in his book, “Wicked Ridgefield, Connecticut,” exploration of the scene of the attack reveals “large pieces of charred wood lying perpendicular to one another” not far from a line of long poles with tips that had been sharpened and burned.” The charred remnants look an awful lot like upside down severed legs, minus feet. Photos are chilling,

Reporters later interview a teenager who claims to be one of roughly a dozen young members of the Satanic Organization of Connecticut, then centered in Ridgefield. Members follow the rituals in the satanic bible, They light candles, chant, wave knives in the air. The young man tells the reporters he has always liked witchcraft and wants to promote devil worship.

( The group, now known as The Satanic Temple — Connecticut and Rhode Island, has its own Facebook page and over 2000 followers.)

Affinity with the devil? Not something you’d volunteer in colonial Connecticut. Such an admission would be tantamount to a death sentence.

For the deeply religious early settlers in New England, God is everywhere, invested in their every move. The devil lurks close behind. Communion with Satan – or being accused of it — is a thing to fear. Anyone convicted of engaging in sorcery is guilty of a crime punishable by hanging…. or worse.

Your next-door neighbor might be a witch … could cause ill health or death, a poor harvest, supernatural or unaccountable events, or dying livestock. You name it. Witches can transform themselves into different creatures like bats or cats so they can cause more trouble while in disguise. They can even ride their victims like horses and bewitch them to obey commands.

It takes only two witnesses to testify that the accused unleashed dark spirits or that the accused stabbed or choked them or caused them psychological distress. It takes precious little hard evidence to convince a jury that someone is guilty of being the devil’s partner.

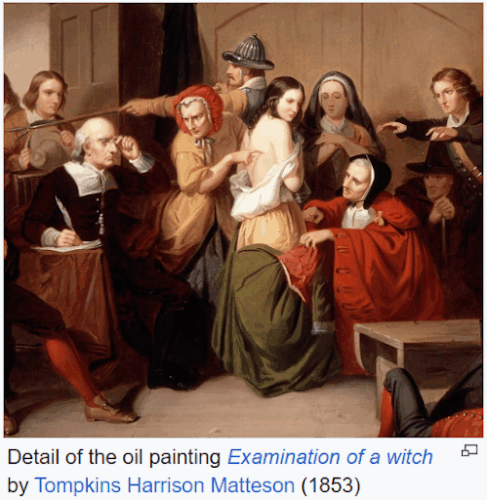

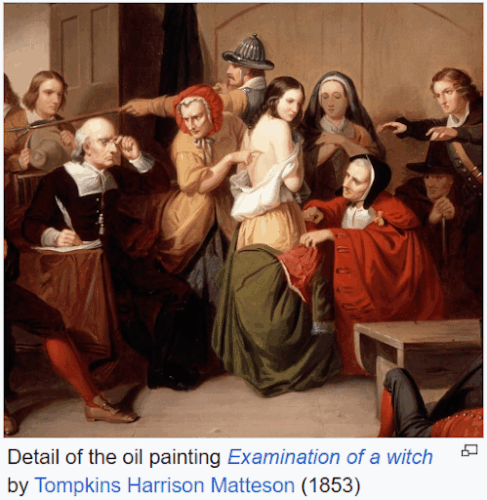

What scenes of horror spectral evidence testimony must have elicited! “Victims” of the witch were encouraged to act and react dramatically during questioning while locals looked on, growing increasingly frightened, vengeful, unmoored, Fear, anger, resentment, revenge…whatever toxic brew motived witnesses to tell tales of disembodied spirits made it nearly impossible for the accused to prove their innocence.

Throughout the mid-to-late 1600s, Connecticut carried out its very own inquisition to root out the devil. The methods used to try, convict, and execute the accused were barbaric. By the time the trials ended, over 40 people – men and women alike – had stood trial, and 16 were summarily convicted and executed by various means. (You can see the names of all those executed here.)

Among these unfortunates was Alys (Alice) Young, whose neighbors in Windsor accused her of being a witch. Perhaps there are undiscovered records somewhere of her trial and of the particulars of the accusations. We know though that Alice Young was hanged for her crimes on what is now the site of Hartford’s Old State House.

Alice’s hanging on May 26, 1647 was the first known witch trial in the new world. The very first in Connecticut, it preceded the famous Salem Witch Trials by several decades. And it would be the first of many.

Mary Johnson, a servant working in Wethersfield, was accused of theft in 1648. Mary was whipped by the local Puritan minister for her alleged crime. She then “confessed” that she was discontent with her many chores, and that “a devil was wont to do her many services.” She also confessed to witchcraft, to “uncleanness with men and Devils,” and even to the “murder of a child.” Mary was found guilty in December of that year and sent to prison in Hartford, where her jailers saw that she was pregnant. Her hanging was postponed until June 1650. (Mary’s son was given to a prison guard who was paid 15 pounds to care for and educate the child. The child served as an indentured servant to his guardian until he was 21.)

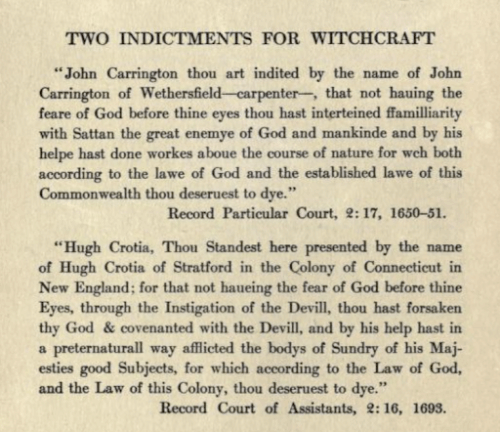

Mary’s trial and conviction were followed a year later by those of John and Joan Carrington, also of Wethersfield. It’s not clear why the couple were charged for entertaining familiarity with Satan and “by his help has done works above the course of nature.” Both were convicted in March, 1651, and sentenced to die. They were hanged at Hartford on March 6, 1651.

In 1697, Goodwife (Goody) Disboro of Westport stood trial. A jury heard testimony from multiple neighbors that they had experienced supernatural events conjured by the woman. Guilt was pretty much a foregone conclusion. The verdict? “Thou hast had familiarity with Satan, that great enemy of God and man, and by his investigation and help, thou has done harm to ye bodys and estates of sundry of their Majesties subjects, for which by the laws of God and this Colony, thou deservest to die.”

Testimony alone wasn’t necessarily enough to convince a jury of innocence or guilt. An accused witch could be subjected to “swimming” or “ducking” – their hands and feet bound before being dropped into a lake or pond. Sink and drown?

Good news — the accused has been accepted by purifying waters and cannot, therefore, be in league with the devil. Float? Bad news –- the accused is clearly a witch. Bodily searches of the accused for evidence of a devil’s mark (a stigma diabolicum) such as a birthmark, mole, or scar were also conducted. Because such blemishes were usually hidden, this could mean a public stripping, close physical examination, and skin pricking. “Witch prickers” were summoned to help suss out witches from the community by repeatedly poking the accused with long, sharp needles. The goal of the torture was to find a mark of invulnerability — a mark that would not bleed or elicit pain when pricked. Not surprisingly, pricking often led to a “confession.”

Witchcraft remained a capital offense in Connecticut until 1715. And though trials may have ended, old beliefs die hard, as the events that befell a local policeman in Ridgefield three centuries later might attest.

But the good people of our state haven’t forgotten the unfortunate souls who were tried, convicted, and executed for practicing witchcraft. More than three centuries after their deaths and burial in unmarked graves *— in May of 2023 – the Connecticut Witch Trial Exoneration Project prompted state legislators to officially declare their innocence. And in August 2024, Hartford held its first ever Witch Trial festival to spread awareness of these largely forgotten trials.**

*To paraphrase the Allman Brothers…. there are no blankets where they lie.

** This year, the Witch Trial Festival will take place on August 9-10.

Susan Kweskin, the author of this article, is a member of the Ridgefield Graveyard Restoration Committee.