Authored by Susan Kweskin

I had a little bird

And its name was Enza

I opened the window

And in-flew-Enza*

The year is 1918. And it’s not going to be a good one.

Alcohol is illegal. Women are fighting for the right to vote. The Titanic — the ship that couldn’t sink — lies at the bottom of the North Atlantic. The RMS Carpathia, the ship that rescued survivors of that famous shipwreck, is torpedoed and sunk by a German submarine. The Czar’s family has been massacred. More than half of American homes don’t have electric lights or power yet.

And hundreds of thousands of young American men are being shipped out to Europe to help win the Great War.

Some of these young men learned how to be soldiers at Camp Funston in Ft. Riley, Kansas. One of the first cases of what became known as the Spanish flu pandemic was recorded in this encampment.

Conditions at the camp made an ideal Petrie dish for incubating contagion. Start by housing 26,000 people in tight quarters. Mix in intense summer heat, dust storms, fierce winds, and long frigid winters. Then add in 9 tons a month of manure produced by the thousands of mules and horses who also lived in the camp. The waste wasn’t used to nourish gardens. Tons of it were burned. The suffocating smoke and ash it produced could be whipped into a frenzy by prairie winds and extreme temperatures.

On March 9, 1918, the soldiers of Ft. Riley awoke to ominous skies – said to be the color of dead black – that heralded a major dust storm. Those encamped couldn’t escape inhaling the toxic haze of dust and ash.

At breakfast two days later, one of the camp cooks came down with a bad cold. He wasn’t alone for long. By lunch, the camp’s infirmary was inundated with more than 100 others – all with the same symptoms as the cook. More than 500 more men followed within the week.

The same malady quickly made its debut in other camps and prisons around the country where it spread as quickly as the ash-laden winds at Ft Riley.

That same month, the US shipped 84,000 soldiers to the battlefields of western Europe. In April, a second volley of 118,000 followed. Somewhere during their voyage across the Atlantic, 36 men came down with influenza. Six died.

The young men on those ships were carriers of something even more deadly than their rifles. The microbial cargo they unknowingly carried promptly set up a beachhead in France, sickening thousands of soldiers on both sides of the fight. So many men grew sick and died – not enough healthy men left standing to do battle.

The virus didn’t quit in western Europe. It spread to most corners of the globe.

The great influenza pandemic of 1918 evolved in three waves. The first wave in the spring of that year didn’t hunt down the very young and very old as the flu usually does. Instead, it stalked young healthy adults with particular venom. Military personnel initially bore the brunt. The second and third waves were more ecumenical: young, healthy civilians – those of child-bearing years with no obvious relation to the military — were in its cross-hairs.

When it was all over, between 50-100 million people had succumbed to The Purple Death. Add to that the roughly 16,000,000 casualties – soldiers and civilians — of war. Numbers so vast they are incomprehensible.

In the April 1919 Connecticut Health Bulletin, Commissioner John T. Black, MD, wrote:

“Consideration of the effect of the epidemic must not stop with the mere enumeration of the deaths. Its sinister characteristic was that it took the strong and the able. It took the potential fathers and mothers. Passing lightly the very young and almost ignoring the old, it aimed straight at the very flower of the flock, selecting the ones on whom the race depends for its present economic strength and its future replacement.”

Infection with the Spanish flu virus began with the familiar chills, sore throat, and fever. Then came slow suffocation. The alveoli that exchange oxygen in the lungs became saturated in fluid, and the victim began to drown. Respiratory failure could ensue — sometimes within hours. Dark spots developed on the cheeks, which quickly evolved into a sinister dusky color. Nurses, overwhelmed with the task of treating the sick and dying, looked to patients’ feet to triage the sickest. Those with black feet were beyond hope.

The scene that awaited the nurses is described this way:

Visiting nurses often walked into scenes resembling those of the plague years of the fourteenth century….One nurse found a husband dead in the same room where his wife lay with newly born twins. It had been twenty-four hours since the death and the births, and the wife had had no food but an apple which happened to lie within reach.

By the end of 1918, roughly one in three Americans had been infected. The flu devastated native Alaskans. NYC lost 33,000; 13,000 died in Philadelphia. Coffins were in short supply; streetcars served as makeshift hearses. Undertakers were inundated:

In some cases, the dead were left in their homes for days. Private undertaking houses were overwhelmed, and some were taking advantage of the situation by hiking prices as much as 600 percent. Complaints were made that cemetery officials were charging fifteen-dollar burial fees and then making the bereaved dig the graves for their dead themselves.

In Connecticut, the flu likely made its entry into ships docked in New London and via men who traveled to that port city from the Boston Navy Yard. By the middle of September, residents throughout the state were falling ill. Danbury residents were among the earliest infected.

The virus came to Ridgefield in September of 1918. It spotted numerous targets. Among them was 35-year-old Margarita Bell Seymour Thomas. She was cut down in her prime on September 27, 1918.

Margarita lies here next to Frederick Dwight Thomas

(1883-1944) — her husband of 5 years — in Fairlawn cemetery. The couple had no children.

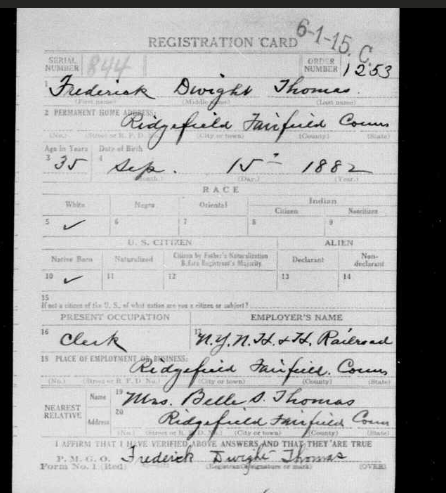

I found little information about Margarita’s life. I learned only that she was born in Ridgefield, as were her parents and brother. I did find Frederick’s draft registration card, signed in Bethel when he was 35. It records that he was a clerk working for the New York/New Haven railroad. He was of medium height and build, had blue eyes, and was partially bald.

It’s striking to see that his registration card is dated September 12, 1918 – almost exactly two weeks before Margarita’s death on the 27th. Might he have been the unwitting vector of infection?

Her obituary, which appeared in the Stamford Advocate, tells of a “fitting tribute to the esteem and respect held for her and the love and affection of relatives and friends, many of whom came from a distance to attend the services.” The same Reverend who had married her five years earlier offered prayer “filled with much tenderness and feeling, which voiced the hearts of the people in imploring comfort and peace for the sorrowing husband.”

Margarita was not the only Ridgefielder to battle the flu. A number of others in a town of roughly 3000 also lost their fight to breathe.* Across this state, nearly 9000 people lay dead. Only those who maintained absolute quarantine (in some schools, asylums, prisons, and other institutions) managed to escape the contagion. Ridgefield schools were not among these: they were kept open during the epidemic and attendance was unaffected. Cancellation of the 1918 Danbury Fair seemed to be the area’s only nod to the risk of infection.

Dr. Black (of the Connecticut Health Department) summed up the devastation:

The epidemic of influenza was a blasting thing, many times more devastating than the war. It was proportionately as harmful to the population of Connecticut as was any year of the war to any of the belligerents engaged.

His words make a poignant coda:

*A “skipping song” chanted by school children in 1918 and 1919.

**The Cemetery Committee of Ridgefield will host a tour of the cemetery complex (intersection of Maple Shade Road and North Street) on May 4, 2024, between 1:00 and 4:00 to honor the memory of those who died of influenza. Please join us!

Bonus quiz question:

- If the flu started in Kansas, why is it called the Spanish flu?

- Spain remained neutral in WWI and was the only country to report the true extent of the pandemic.

- Spaniards were largely spared from the influenza pandemic.

- More people in Spain died from influenza than in any other country.

The Ridgefield Graveyard Restoration Committee, which is an official town committee, invites townspeople to a self-guided tour at the town’s main cemetery complex, at the intersection of North Salem Road, North Street, and Mapleshade Road, on Saturday, May 4, 2024 from 1 to 4 p.m. (rain date: Sunday, May 5, 1 to 4). There is no admission charge; freewill donations can be made to the Ridgefield Historical Society. The theme will be “Not the best of times!” The committee is highlighting some of the graves of Ridgefielders who are believed to have died in the great Spanish flu epidemic of 1918-19.