Download PDF

Tender Civil War letters from a young soldier are a new addition to the Scott House archives

In 1862 and 1863, a Union Army soldier wrote long letters home to his wife, sharing his day-to-day life. He described the tedium and uncertainty as the troops trained and then prepared for engagement and he always spoke of his longing to be back with his family.

Edwin Darling Pickett left for military service around Sept. 1, 1862; on July 1, 1863, Sgt. Pickett died of wounds suffered in the first day of fighting at Gettysburg. He was 28.

The Ridgefield Historical Society recently received a collection of his letters, the gift of Jean B. Gerrity of Madison, in memory of her mother Ann Piccirillo Zaccaria, from whom she’d inherited them. The historical society is grateful to Ms. Gerrity for placing this piece of Ridgefield history where it will be available for study in the years to come.

flags at the gravestone of Sgt. Edwin Pickett in Titicus Cemetery. From left were Doug Clewell, Fred Layda, Rick DeWald, and Richard Klahn. —Scott Mullin photo

In one of the first letters in the collection, Pickett is stationed at Fort Marshall in Baltimore where his unit, the 17th Connecticut, Company G, was posted. “darling wife,” he begins, then explains he’s rushing to get the letter into the mail. He had time to write because he’d gotten a doctor’s order for a day off from the brutal training that he and his fellow soldiers were enduring.

When I have more time to write I will tell you all about how business is managed here. I believe our Col is a rascal and is backed up by a lot of Capt. and they are trying to make all the money they can off of it. We get 7 hour drill every day but Sat & Sunday. It will kill the men, it is hot and the men are weak and can’t stand it.

After thus sharing his opinion of the regiment’s officers (for his wife’s eyes only, he warned), he promised to do his utmost to get through his service and make his way home.

Bless you Darling, for the first time I was homesick last night. I wanted to see you all. I need not tell you I cried.… You know Darling how much I love you and Willie and how I long to see you. I thought if we had to leave here I would keep all right to march if they get me down. I’ll bet they will be smarter than I am. It is about mail time so my dearest goodbye for the present. Love to all and remember me as your affectionate husband.

Edwin Darling Pickett was born in Ridgefield in 1835, a son of Rufus H. “Boss” Pickett and his wife, Betsey Parsons Pickett. “Boss” Pickett was a noted furniture-maker in town; his first shop was on Main Street, opposite today’s Christian Science church, and he later worked from a building on Market Street. The Pickett home was on the north corner of Main and Market Streets. In 1857 Edwin Pickett married Sarah Chickering Harrington — a descendant of a Revolutionary War captain — in Taunton, Mass., and four years later, they had a son, Edwin William Starr Pickett, known as Willie.

There is no date on the following short note, but it’s believed to be from February 1863, when Sgt. Pickett knows that his second child may be born.

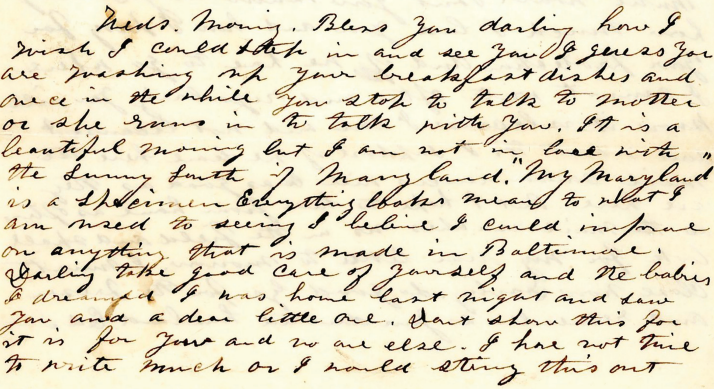

Weds. Morning. Bless you darling how I wish I could step in and see you I guess you are washing up your breakfast dishes and once in the while you stop to talk to Mother or she runs in to talk with you. It is a beautiful morning but I am not in love with the Sunny South if Maryland. “My Maryland” is a specimen. Everything looks mean to what I am used to seeing I believe I could improve on anything that is made in Baltimore. Darling take good care of yourself and the babies I dreamed I was home last night and saw you and a dear little one. Don’t show this for it is for you and no one else. I have not time to write much or I would string this out until noon. But you know my Darling how much I love you and how I pray for your protection. And if we have to go where I cannot write often and regularly you will know it is because I can and not because I don’t want to. I suppose if we leave here the mail conveniences will be as good as they are here. But I hope to hear from home as often as the mail reaches us in the field and shall look for my dear letter tomorrow. I must close now Darling, so goodbye for the present and remember as your devoted husband Ed.

Late in June 1863, the 17th Connecticut was back in Maryland, after having been part of the Chancellorsville Campaign (April 27-May 6). They were unsure of what would come next or where the action would be, although there were indications of Confederate movement. Three days before the battle at Gettysburg began, Sgt. Pickett wrote to his wife, Sarah:

My Own Darling,

I wrote you yesterday that I would write again today. We changed camp yesterday and are now about the same distance from the town only in a different direction. We lay along side the Haggerstown road and hear the Rebs are marching up towards Chambersburgh Pa. If so we may move soon, but we may stay here 10 days and may not stay an hour. This is a good union town: out of 800 votes only 8 was for the C.S.A. the rest for U.S.A. I am very well and enjoy myself as well as I can away from my own dear ones. If I could only come and stay with you I would willingly march all the way.

….I have in my hand the last letter I rec’d from you. Bless you darling for such dear letters they do me so much good. I suppose you get all the news from the papers we don’t get any papers now and don’t know what is going on in the world. I hope it is time that Vicksburgh is surrendered. It seems as if it could not hold out much longer at any rate. I would give a great deal to see and hear our boy perform as I think he must be very funny sometimes.

….I heard a church bell ring this morning for the first time in over 8 months. It did sound good I tell you and I wanted to go to church again. I don’t know what Hooker is doing but it is the general oppinion that the Rebs are in a bad scrape and can’t get out again for we are after them sure now. You say I don’t know how you want to see me. I can imagine by my own feelings some I can tell you for my heart and thoughts are with you all the time and many times a day do I ask for blessings to rest upon you.

This a most beautiful country and a great deal of grain is almost ripe. The inhabitants are rejoiced to see us for they heard the Rebs was comming to destroy their grain and they did not know of our comming until we marched into town. Many had hid their horses and after we come they got them out again. I wish I could see you and tell you all for I can talk faster than I can write, if anything I can talk faster than I used too when I was home. It is hard writing sitting flat on the ground and I can’t write very good. I wrote a short note to Stan yesterday as I thought he might like to hear what had become of me. Our 1st Lt has gone to the Hospital in Georgetown and I guess he will resign as he said he meant to as soon as he could get to Washington. He is not here and sent in his papers and they would not accept of his ressignation but I guess he will go now at any rate. If he does I shall expect a chance. If so it will be by my own exertions and no thanks to any one. I have much to write and could fill another sheet but I will try to write again in a few days and let you keep track of me. Kiss my dear boy for me and tell him Pa Pa loves him. Write as often as you can. I am in hopes we will not have to go into Virginia again for if we are successful in this I think we will come home. Give my love to all, tell Wm to write to me, are they raising any new troops in Mass. Good my Darling a lot of good hearty kisses and all the love of my heart I am as ever your true and loving husband.

Among the 3,155 Union soldiers who died at the Battle of Gettysburg was Sgt. Edwin D. Pickett, who succumbed to his wounds on July 1 after a fierce fight at a place later known as Barlow’s Knoll. It was so called for Brig. General Francis Barlow, who ordered the 11th Corps to take the raised ground, then saw his troops overrun by Confederate forces and pushed back into Gettysburg.

According to Charles Pankenier in his book, “Ridgefield Fights the Civil War,” Eddie Pickett was now a first sergeant. “As ‘orderly,’ he was entrusted with running the company in the absence of its captain, and in preference to the lieutenants who were his nominal superiors.” As Company G advanced to the fighting on Barlow’s Knoll, Pankenier wrote, “They were led by the flags that were the symbol of regimental honor — and a high-profile target,” Pankenier said. “Years later a comrade would recall: ‘Here Orderly Edwin D. Pickett was shot down while grasping the regimental colors, being the third bearer, who had carried them to the death.’ ”

Word of Sgt. Pickett’s death was received in Ridgefield on July 6. His brother, Rufus Starr Pickett, known as Starr, went to Pennsylvania to retrieve his brother’s body and, according to Anna Resseguie’s diary on July 12, “searched some time among the dead at Gettysburg before he was found; his blanket was wrapped about him, his watch and pencil given by Starr, were in his coat sleeve.” Miss Resseguie, daughter of the innkeeper at what is now called the Keeler Tavern, also reported that at the July 12 funeral, “a long procession of pedestrians, as well as carriages, followed his remains to the grave.” “Sergeant Edwin D. Pickett … was a favorite with the men, and much esteemed in Ridgefield, where he lived. On the Sunday of his funeral, the churches suspended other services, and united in the tribute to his high personal character and his manly virtues. To his children he left the legacy of an unspotted name and a record of noble deeds.” (The Military and Civil History of Connecticut During The War of 1861-65)

The Ridgefield Historical Society archives also contains a letter from Aaron W. Lee to his father in Ridgefield, describing the battle and its aftermath. A member of Company G, he was wounded at Barlow’s Knoll and made his way to a makeshift hospital in Gettysburg, where Sgt. Pickett lay nearby.

I had just drawn a good sight on a strapping big Reb and fired and got hit myself at the same time. I looked around and seeing a barn close by I took my rifle for a crutch and drew myself for it. Here I saw Col. Harris of the 75th.§ He said they had taken the Alms house for a Hospital and I stopped there and in a few minutes the Rebs came in and took us prisoners. Edwin D. Pickett must have been wounded about the same time as I was. I did not think he would die that night. I lay down within six feet of him. The next morning I woke up and spoke to him but got no answer. I went to him and found him dead.

Sgt. Lee was freed by Union forces and eventually transferred to a military hospital in Philadelphia, where he wrote the letter describing the battle. He returned to Ridgefield after the war and lived until 1890.

It was Sgt. Lee who suggested the new GAR (Grand Army of the Republic, an organization for Civil War veterans) post be named for his fallen comrade, and for many years the Edwin D. Pickett Post of the GAR was a major organization in Ridgefield. In 1884, it played host to the Connecticut GAR reunion that included a parade of 400 Civil War veterans down Main Street, watched by some 2,000 people.

Co. G 17th Regiment Conn. Volunteers

1830-1890

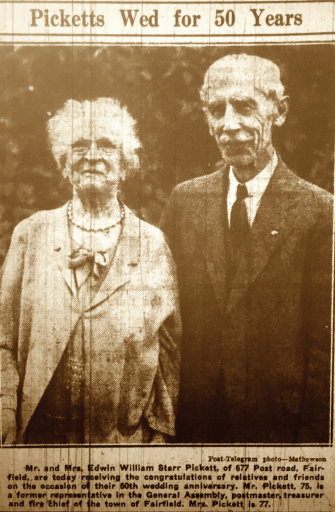

Sgt. Pickett’s son, Willie (Edwin William Starr Pickett, 1861- 1937), grew up and later made his home in Fairfield, where he dealt in real estate and insurance. Sgt. Pickett’s widow, Sarah Chickering Harrington Pickett, married Jacob Hall Fuller in 1874; she died in 1901 and is buried in Hampton, Windham County, Conn.

The grave of Sgt. Edwin Darling Pickett is in the Hurlbutt Cemetery in the Ridgefield cemetery complex; the weathered stone, once-broken and repaired, features a bas relief medallion of a hand holding aloft the flag of the United States.

Sadly, the Ridgefield Historical Society has no image of Sgt. Pickett, but his letters create a vivid picture of a young man who loved his family deeply and had great plans for their future.

The Scott House Journal (SHJ) is a quarterly publication, sharing stories of Ridgefield past. It is written by Sally Sanders, Historical Society Board member and former arts editor