Download PDF

St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church:

Three Centuries in the Heart of Ridgefield

When Ridgefield was settled in 1708, the church, the citizens and their government were all one: It was a congregational society, where members of the local church made the decisions, unfettered by any higher ecclesiastical authority.

The town’s establishment came just a year after the first Church of England parish formed in Stratford. Church of England worshippers followed the episcopal tradition, where churches were governed by bishops, while the Congregationalists who settled Ridgefield organized their own churches and selected their own leaders.

For the early churches affiliated with the Church of England, this meant that decisions and

ordinations were in the control of the Bishop of London.

Not until 1725, when the Rev. Samuel Johnson, from Stratford, began to preach to Ridgefielders, did a Church of England parish begin to form here. It was known as the First Society in Ridgefield—Church of England until 1831 when the name St. Stephen’s was chosen.

Now, St. Stephen’s Church celebrates its 300th anniversary, a familiar and historic presence in the center of the Ridgefield village.

In the church’s early days, Ridgefield was a missionary outpost with ministers often traveling good distances (from Norwalk, from Newtown, from New York State). By 1735, the Rev. John Beach told associates that there were “nearly twenty families of very serious and religious people, who had a just esteem of the Church of England and desired to have the opportunity of worshipping God in that way.”’

All of the clergy who served in Ridgefield until the American Revolution were missionaries of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts (based in England) and were supported by the SPG as well as by the local property tax that was apportioned to the church beginning in 1738. The Ridgefield proprietors agreed in 1740 to provide land for a church, on property formerly belonging to John Sturtevant, who had died.

A building was erected about where the present church stands, according to church historian Robert Haight, but “like all other colonial churches, could not be consecrated since there was no colonial bishop.” The church was used from its completion in 1740 until the Revolutionary War when it was partially burned by the British in the Battle of Ridgefield (it had been requisitioned to house supplies for the Patriot forces).

Ridgefield had decided the question of its allegiance in favor of independence from England, but not without a struggle. The first Town Meeting vote repudiated the Continental Congress and acknowledged “his most sacred majesty King George ye 3rd to be our rightful Sovereign.” However, by the end of that fateful year, 1775, the Town Meeting was ready to “disannul the resolves enter’d into and passed, on the 30th of January, 1775, and adopt and approve of ye Continental Congress, and the measures directed to in their Association, for securing and defending the rights and liberties of ye United American Colonies.” There were no objectors.

From 1768, the Ridgefield parish had been served by the Rev. Epinetus Townsend, who had been ordained in England in 1762 and also ministered to parishes in Ridgebury and Salem (NY). He was an outspoken Loyalist, preaching sermons against the rebellion, “before and even after the Declaration of Independence,” according to Haight.

Eventually though, “he was subject to severe treatment at the hands of the patriots. Like many other Church of England missionaries, whose loyalties precluded the continuance of their ministries, Mr. Townsend fled to New York, a Tory stronghold,” Haight wrote.

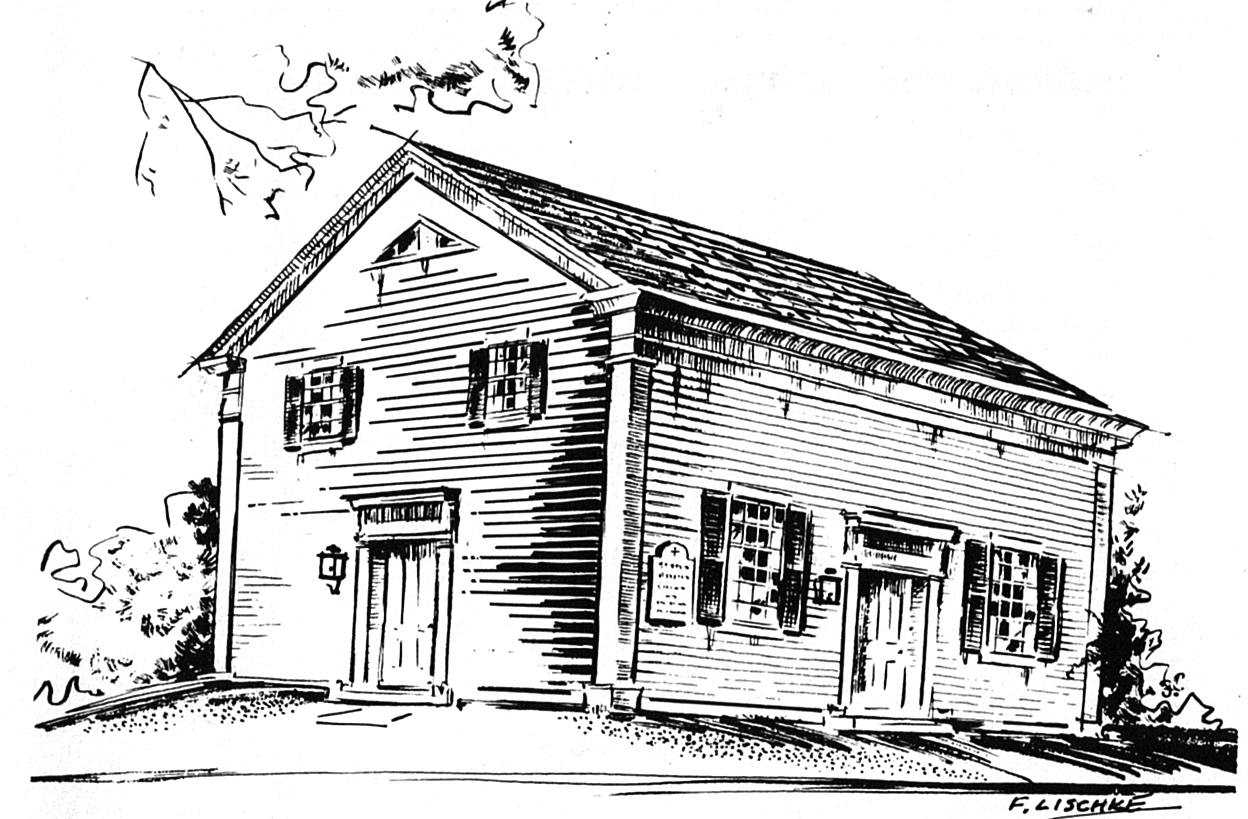

According to St. Stephen’s historian Robert Haight, “The church was completed in March 1791, about seven years after the inception of the project… It was a brown wooden structure, 44 feet in length and 32 feet in width. It had two entrances, one at the south end and one on the east side which was parallel to Main Street. The church had a gallery at the south end reached by a stairway near the rear on the west side. Of course, there was no heat or light in the building.”

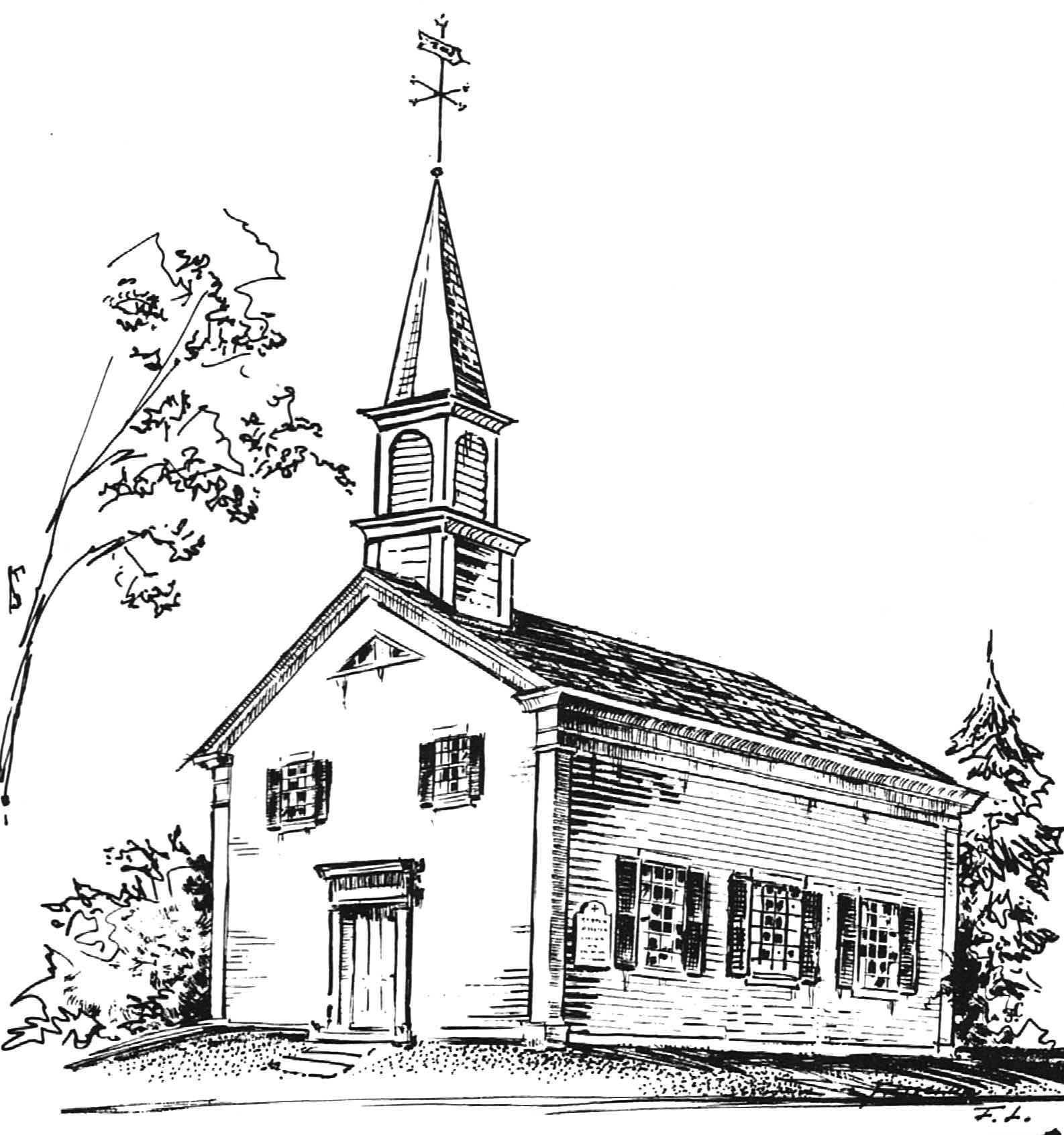

A steeple was added to the church building some years later and a bell was installed in 1828; in 1831, the church was consecrated by the Rev. Bishop Brownell, who confirmed 52 persons. At this time, the church was named St. Stephen’s. By 1841, it was decided to build a new church on land donated by Isaac Jones to augment the original property owned by the parish; the cornerstone was laid on Aug. 12, 1841. This church would be oriented as the current one is: with the entry in the east end of the building and the altar and pulpit to the west.

In his book, The History of Ridgefield, the Rev. Daniel W. Teller notes that in the new church, “Tablets were also placed in the walls of the church in commemoration of two venerable laymen of the parish, one to Samuel Stebbins, Esq., the other to Nathan Dauchy, both firm and zealous supporters of the Church in all its vicissitudes — the former a distinguished and useful citizen of the town, as well as of the parish; for forty years the town clerk and during a period of forty-six years the parish clerk, and for over forty years the senior warden of the church.”

With the construction of the third church building, the parish was able to begin Sunday School, an important element in the religious life of member families. Ridgefield’s population grew and changed with the arrival of the railroad in the mid-19th Century, making a trip from New York into the center of town much more convenient for wealthy New Yorkers who began to build their “summer cottages” around the village. Many of these new families worshipped at St. Stephen’s.

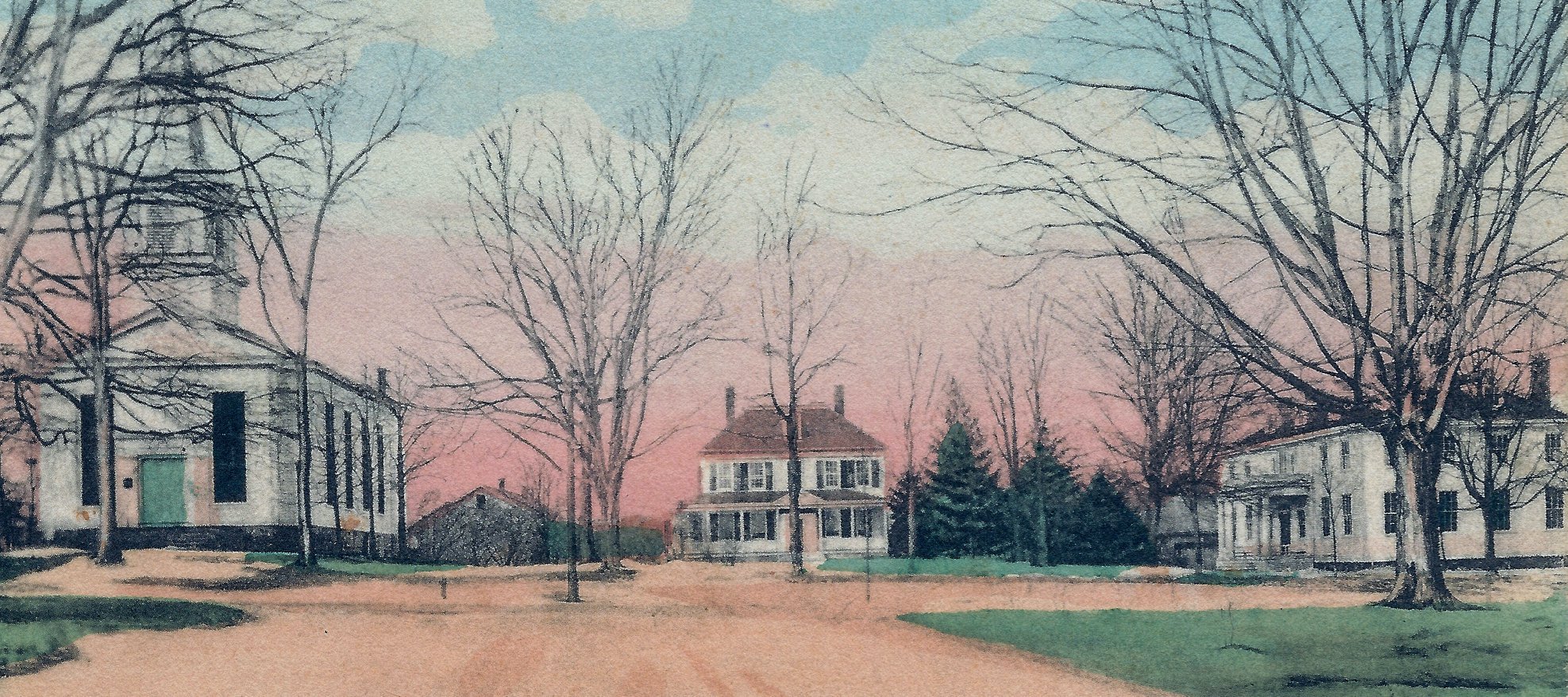

In 1909, a new church house, now called North Hall, was added, providing needed meeting space for church organizations as well as for other town groups. The rectory, which sat in between the church and the new hall, was moved westward about 50 feet, according to historian Haight, to form “a quadrangle of attractive proportions.”

By 1913, discussions focused on renovations to the 70-year-old church building, which had a number of structural problems. Eventually it was decided that a new church would be built. Its site was a matter of some controversy, according to Haight, who wrote that the vestry favored placing the new church on the site of the rectory, while the building committee favored rebuilding on the site of the third church. The building committee, which prevailed, included many prominent residents: Mrs. D. Smith Sholes, Mrs. F.E. Lewis (who resigned within a few weeks of joining and was replaced by Albert E. Storer), Miss Mary Olcott, E. P. Dutton, Jonathan Pulley, and William Bunker.

After considering three architects’ proposals for the new church, two of them Gothic designs, the building committee selected the Colonial-style church proposed by W. Kerr Rainsford of Allen & Collins of Boston. (Mr. Rainsford’s father, Dr. William S. Rainsford, a retired Episcopal minister, lived at Savin Hill, now known as Le Chateau, just over the state line in South Salem, N.Y.)

In the building committee’s report, written by Mr. Bunker, he explained the choice: “At first the plans for the new Saint Stephen’s took shape about a Gothic building but the old Colonial traditions of the civil and religious life proved too strongly grounded in the hearts of the people. It seemed best to us (the Committee), therefore that a Colonial church should again rise upon the old site.” The plans for the Georgian structure were unanimously accepted; Mr. Rainsford also designed the interior, including the pews, pulpit, altar, and chancel furnishings.

The low bidder for the project was Ernest Scott of Ridgefield; demolition of the old church began in May 1914 and the cornerstone from the old church was laid for the new one on June 28, 1914. In less than a year, the new church was completed and the first service in it took place on May 2, 1915. The church was consecrated on May 30, 1916, following a month of turmoil, as the financial records for the building project and other church funds were found to be in a state of disarray, with a deficit of about $13,000. Cyrus A. Cornen, Jr., resigned as treasurer on May 28 and was replaced by Seth Low Pierrepont; an urgent fund-raising effort had cleared the debt in just four weeks, allowing the church to be consecrated.

It turned out that Oatland, the 351 Main Street former home of the Rev. James Tuttle-Smith, would be given to St. Stephen’s Church in 1958; it had been the offices of Electro Mechanical Research, headed by Henri Doll of Spectacle Lane. As South Hall of St. Stephen’s Church, it briefly contained the offices of the Ridgefield Board of Education and later had an apartment used by the associate rector. Since May 2021, it has been restored and returned to its original use as a private residence. With the sale of 351 Main Street, St. Stephen’s reconfigured and rebuilt its parking area behind the church, rectory and North Hall.

One of the church’s great community traditions had been the Nutmeg Festival (so named by the Rev. Aaron Manderbach in the mid-20th Century), which filled the church grounds visitors and fund-raising booths. What began as an Apron and Cake Sale on the porch of the rectory 1892, grew into an event that drew thousands to Ridgefield; it made its final appearance in August 2018.

A church that was founded in Ridgefield’s early days, that endured the upheaval and aftermath of the American Revolution, and that has grown and changed with the town, now embarks on its fourth century as an integral part of the community and a historic presence in the center of town.

Special events throughout 2025 will mark the tricentennial of St. Stephen’s Church, including Homecoming Weekend on Sept. 27-28. For more information, click here.

The Scott House Journal (SHJ) is a quarterly publication, sharing stories of Ridgefield past. It is written by Sally Sanders, Historical Society Board member and former arts editor