Download PDF

Saving the Branchville Schoolhouse: First steps

The Ridgefield Historical Society was founded to preserve, interpret, and foster public knowledge of Ridgefield’s historical, cultural, and architectural heritage. The work began with the re-purposing of the 1714 Scott House as the society’s headquarters, which opened in 2001 with a vault designed to protect materials that tell the town’s history.

In 2011, the Ridgefield Historical Society became the caretaker and interpreter of the Peter Parley/West Lane District Schoolhouse, which had been restored as a small museum by the Ridgefield Garden Club, which leased the building from the town for 50 years.

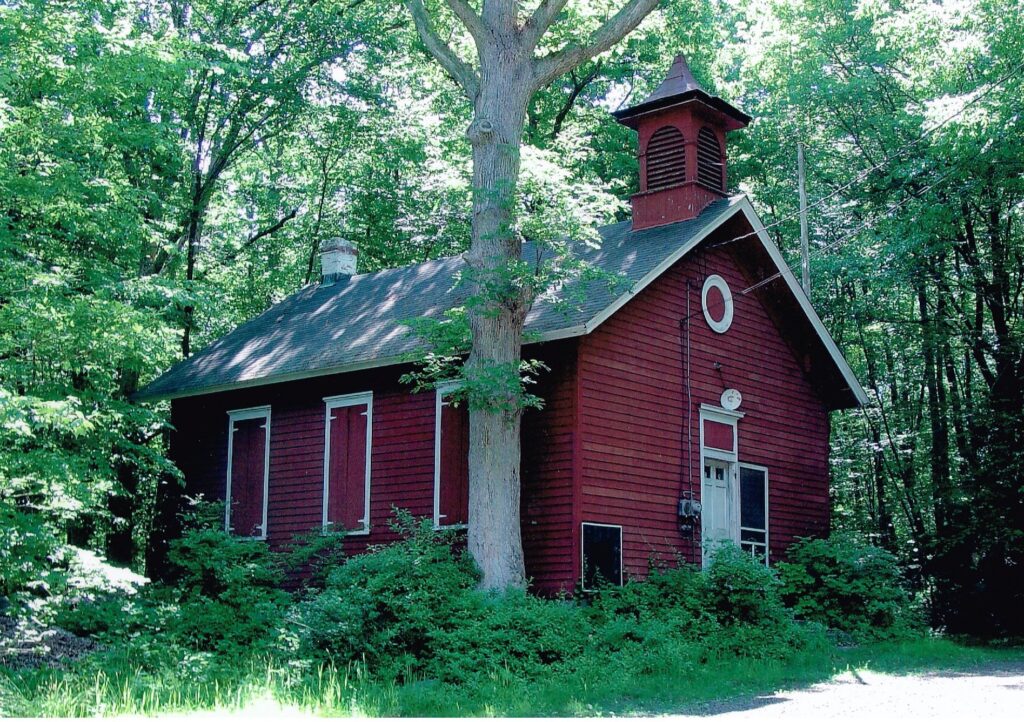

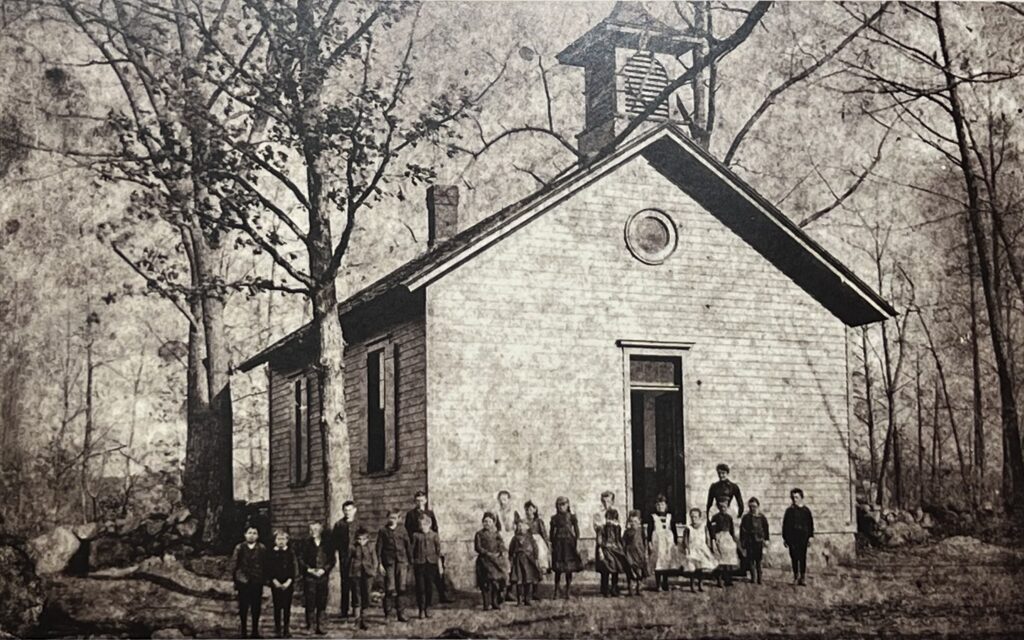

Now, the Ridgefield Historical Society and supporters want to give the circa-1872, one-room Branchville Schoolhouse, which served District 10 until 1939, a new and useful life.

The Ridgefield Historical Society board of directors has voted to pursue the school’s restoration and preservation, in partnership with the Town of Ridgefield. First steps to protect the building are underway, in the form of a study of the building to gain its listing on the Connecticut Register of Historic Places, which makes the schoolhouse work eligible for grants. The board’s vision includes a multi-year lease agreement with the Town of Ridgefield, during which the Historical Society will oversee the restoration of the building. The goal is to secure the schoolhouse’s place in the future, ensuring it benefits our community for generations to come.

The restoration and fundraising process is expected to span approximately five years. The Ridgefield Historical Society will lead fundraising efforts in collaboration with community groups and key individuals. Experienced contractors and architects with an understanding of historical preservation and adaptive reuse will carry out the restoration work, closely guided by the Ridgefield Historical Society to preserve the building’s historical integrity.

The project will encompass both the exterior and interior, focusing on repairing and restoring the roof, cupola, siding, windows, and doors. The interior will be renovated to serve as a museum documenting Ridgefield’s history and the generations of Ridgefield families who attended school there, as well as a community meeting space.

‘Modern’ in its day, the Branchville Schoolhouse served generations of Ridgefielders

Dating from around 1872, the Branchville School- house was probably built from plans provided free of charge by the state. Featuring some of the latest 19th Century “improvements” in schoolhouse architecture being promoted by the education professionals in state governments and universities, the District 10 School replaced an earlier one on the same site and had a much taller, airier classroom, a better ventilation system, and bigger windows to let in more light. It’s unknown whether there were originally separate entrances for boys and girls — the building currently has a single front door.

There was a well on the property, unlike at some of the district schools where water had to be brought in from another property (usually a neighbor). Up until it closed in 1939, the school had only an outhouse; no running water. In his book, School Days, Schools and Schooling in Old Ridgefield, historian Jack Sanders wrote, “The pupils were evidently proud of their new school. A brief but fascinating news item appeared in The Ridgefield Press in July 1877 when the children at Branchville announced they would have an ‘Ice Cream Festival’ at the schoolhouse to raise money ‘to procure new books and a bell.’ The fact that a school bell was being sought suggests that the building was still being equipped.

“That same month, Episcopalians who, with Congregationalists, had been using the new school- house for special Sunday services, decided to take up collections to buy an organ for the schoolhouse. The announcement of this organ fund drive in The Press was a rare mention of a schoolhouse being used as a church long after the era when churches were used as schoolhouses.”

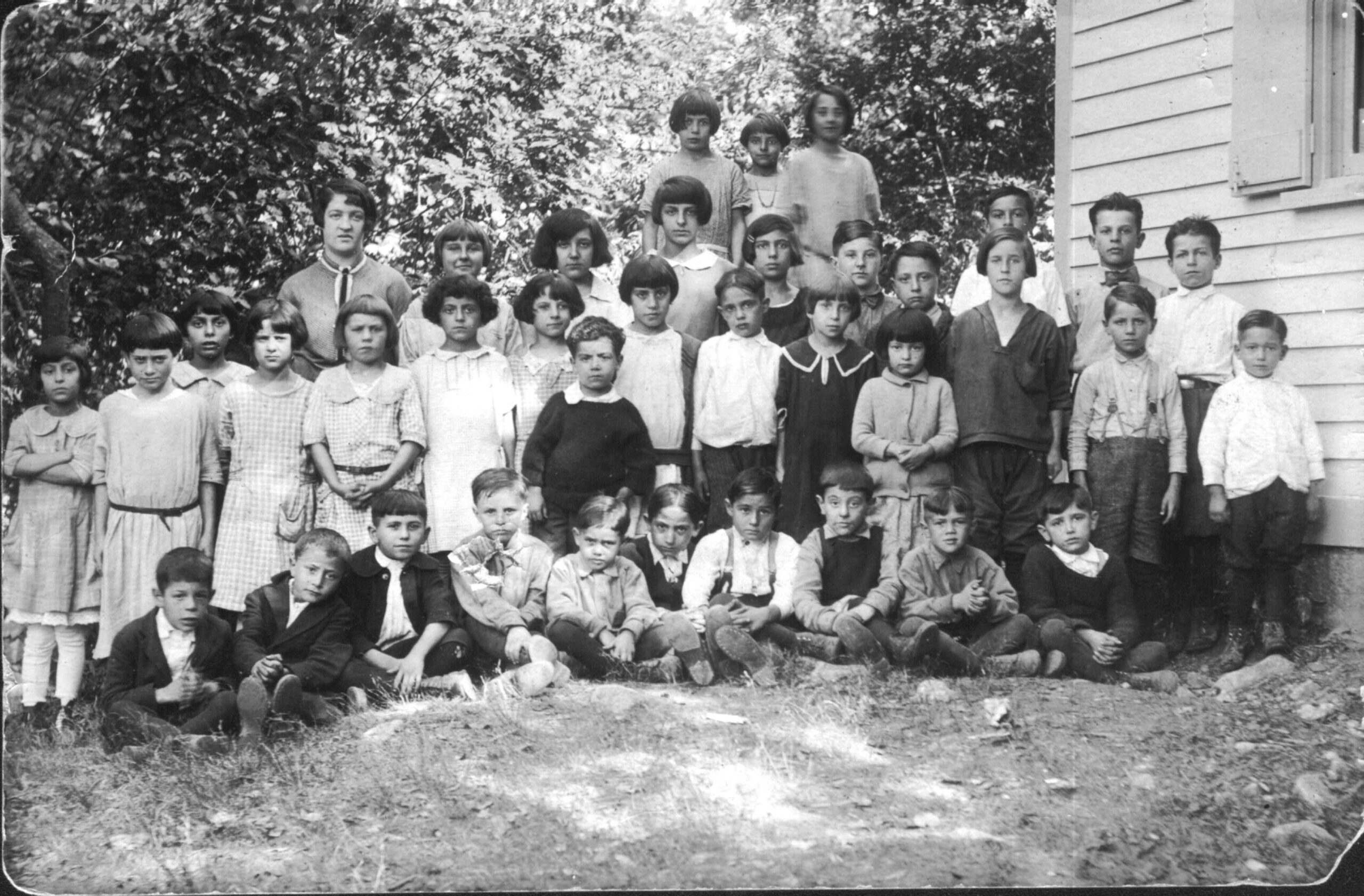

By 1926, of the 741 children enrolled in the Ridgefield schools including high school, 28 were at Branchville, a number that dropped to 24 by 1931. Finally, in June of 1939, the last of Ridgefield’s district schoolhouses would close: Titicus and Branchville. (Ridgebury closed in 1929 and Farmingville in 1937.)

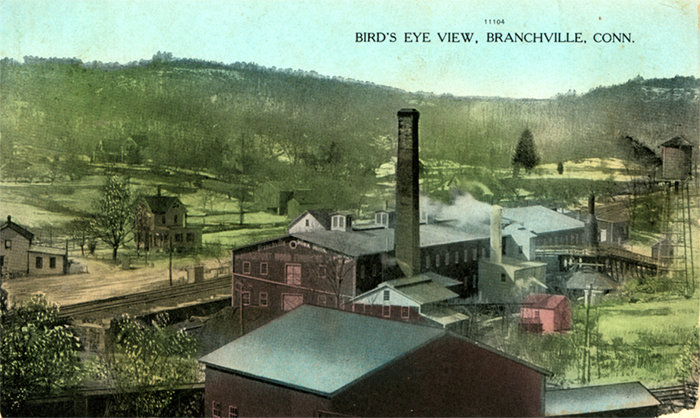

The Ridgefield Historical Society’s archives include several oral histories recorded with former students at the Branchville School, which served the community that grew up around Ridgefield Station with the construction of the Danbury and Norwalk Rail Road in 1852. Following the opening of the railroad’s branch line to the center of Ridgefield in 1870, the area became known as Branchville.

Bertha Antognetti Muccini, born in 1913, was interviewed in 2005 by Betsy Reid for the Ridgefield Historical Society oral history collection; she grew up in Branchville. Her father was born in Castelvecchio, Italy, and her mother came from Ripalta, Italy; Ms. Muccini was born in Bridgeport where her father worked for Remington Arms during the first World War. “Somehow, I don’t know why he wanted to move here to Branchville, but I think it was because he had a lot of relatives in Ridgefield. [His mother’s maiden name was Bedini.] When he came up here, he found work in the Georgetown wire mill, and from there he worked on the railroad, and then he became… a mason, a stone mason, and he did masonry work. He got his own business eventually, after many years.” Mr. Antognetti built the stone building known as the Antognetti Tool Company on Peaceable Street next to the train tracks and also did stonework at Moongate, the home at the bottom of Florida Hill Road.

Bertha married and moved to Westchester but later returned to the family home after she was widowed and continued to live there with her sister Nan; she died in 2009.

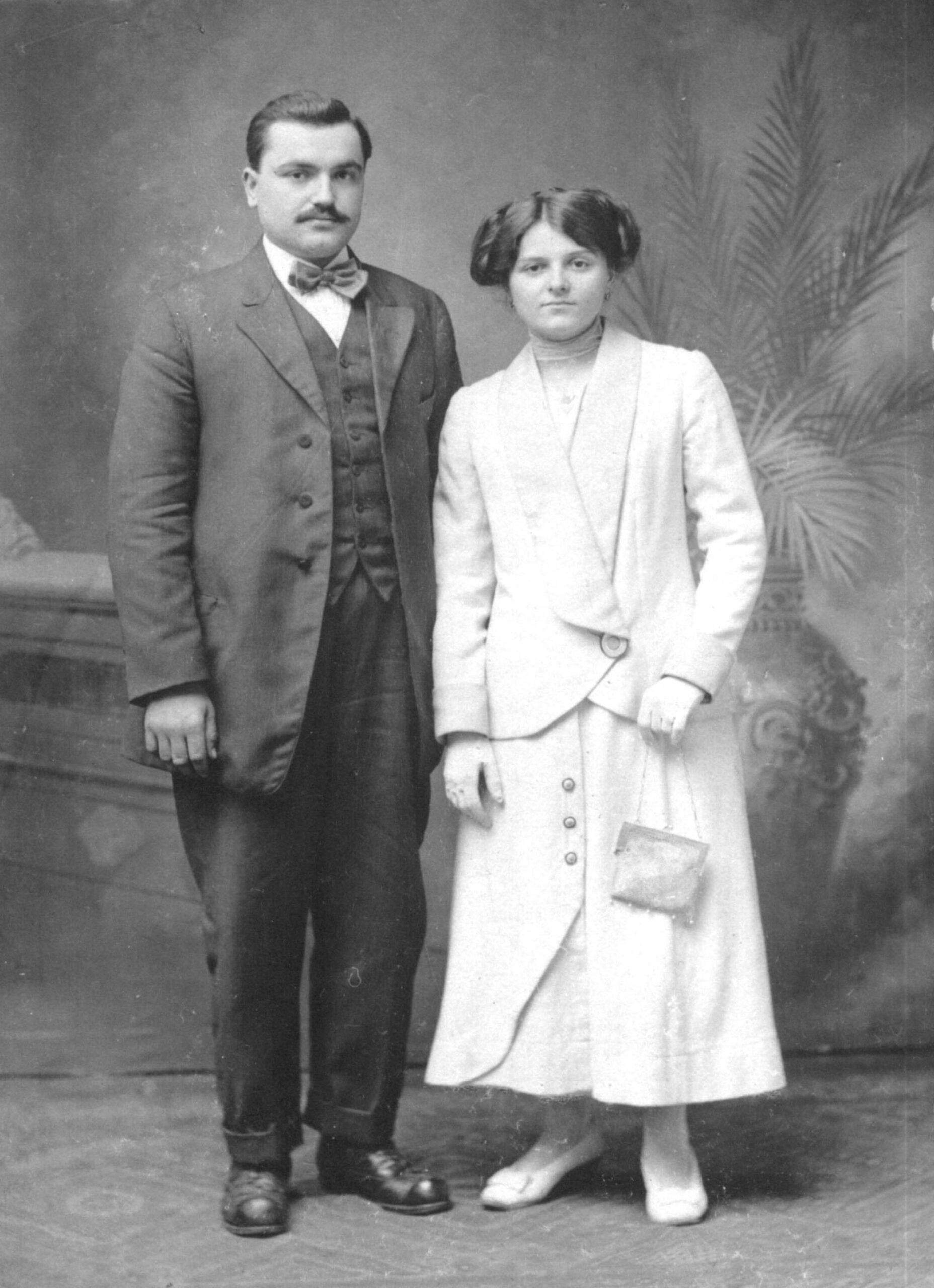

Like many young men in Italy, Nicola Antognetti had left home to find work; when he was 17, he came to work at the Port of Missing Men, building roads for H.B. Anderson’s project on the Ridgefield/North Salem border. Lavinia Serralegri and her family came to Bridgeport in the early 1900s and she later met Nicola Antognetti, a handsome young man who played the accordion; they married when she was about 17 and he about 21. Their family grew with the births of Bertha, Nan, Corrado and Augusto.

The memorable ‘Miss Archer’

When the family moved to Branchville, they had a house just up the Peaceable Street hill from the DeBenigno store, across what is now called West Branchville Road from the train station.

Bertha’s schooling had started in Bridgeport at the Madison Avenue School and like many immigrants, she was learning English in the classroom. That continued at Branchville, which she attended from first through fifth grades. Sixth grade, she told Ms. Reid, was at the Ridgefield firehouse and then it was on to junior and senior high school at the brick school on East Ridge.

The five years Ms. Muccini spent at Branchville School were all led by the school’s sole teacher, “Miss Archer.” [That was Muriel Archer, hired in 1925 to teach at Branchville; she commuted on the Danbury-Norwalk rail line from her home on Greenwood Avenue in Bethel.]

She was someone Ms. Muccini remembered well: “Oh, I can’t forget her.”

“Why?”

“I’ll tell you why! She used to love to talk to us. She would say… she would tell us… alright, first class, do this, second class, do that. And then all of a sudden when she would come to the fifth class she would tell us a story of what happened to her on the weekend. She had a Model T Ford and she had this big suitcase that she attached somehow to her car. She had all her gowns in there, her silver slippers in there. She had everything for the dance floor. She used to go to these dime-a-dance places, did you ever hear of that?”

“So when she came back on a Monday, she started to talk to us older children. She says, ‘I lost my suitcase going into New York.’ She says, ‘I don’t know how I lost it.’ …. Well, you know, as children… well, I was about 10 years old by that time, we snickered, you know, we thought that was funny.

“She didn’t think it was funny. No.”

At 92, Ms. Muccini still had sharp memories of the school. Recess, she recalled clearly. “We used to have a well there. I think it’s still on the grounds there. If we were thirsty, we went to the well with… they had a dipper and a pail of water. You put the pail down [into the well] with the rope and pull it up, and then have your dipper and drink. Very unsanitary, I must say!

“And then, during recess, when the bell rang we went back. We had to hear the bell first, we couldn’t go in the little schoolhouse unless it was winter and spring. Spring she [Miss Archer] would let us stay out, like around May, because it was cold in those days, it’s not like now. It was very very cold.”

When it snowed, which Ms. Muccini said could happen as late as May, her father “used to have a shovel with him and escort us for a little ways, until he got tired, and then we would trudge in that snow with our boots.”

“I remember coming home from Branchville School one time, I was soaking wet. I went to school without boots, of course. It wasn’t snowing. But when I came home, there it was. There was over a foot of snow and my socks were soaking wet. And my Mom says, ‘Oh you poor kids. Come here. Come here.’ So she pulls a chair out in front of the oven door, she opens the oven door… and she says, ‘Now you sit here and I’ll take your socks off and we’ll dry them.’ So we sat there. Our feet were frozen, you know. You can imagine what a feeling that was. I would like to see children today do that.”

Ms. Muccini recalled that in good weather, children of her era “had fun. We thought it was fun, anyway. Marbles, I still have marbles from way back when. The hoop. We used to like the hoop. There was an iron hoop and I believe it was made with a stick and a nail in it, and you got it going and you ran with it. Sledding, we did a lot of sledding.”

Bertha Antognetti Muccini is just one of the many Branchville children who started their education at the Branchville Schoolhouse; some were learning English as they went along, while others were from longtime families, descendants of the early Ridgefield settlers.

The Branchville Schoolhouse is not just any building; it is one of two remaining intact one-room schoolhouses in original condition owned by the town. However, the ravages of time have taken their toll and urgent restoration is required to safeguard it and prevent further deterioration. Ridgefield at one time had as many as 17 school districts and at least 15 district schoolhouses (some of the districts were half-districts, shared with an adjacent town; Branchville was originally a half district with students attending a nearby Georgetown school). Several of Ridgefield’s one-room schools were sold and moved, repurposed as homes; one traveled all the way to North Salem to become an artist’s studio. The old Titicus School, the only three-room district school, now serves as headquarters for the American Legion.

On an old highway

Unlike the town-owned Peter Parley/West Lane District School, which sits at a prominent intersection, the Branchville Schoolhouse is set back from Old Branchville Road and is now surrounded by trees and shrubs that have grown up since it was used as a school. While it was once on the main road to town, its location is now off a less-traveled route.

According to Jack Sanders in his book, Ridgefield Names, “Old Branchville Road is another highway whose ‘old’ refers to its replacement as a main road by a newer road. In this case, the newer road is a section of modern-day Branchville Road, Route 102, that was built in 1851 to improve wagon transportation to and from the new train depot about to open at what we now call Branchville. …Old Branchville Road is a very old highway, part of a road laid out by the ‘Select Men’ on Dec. 26, 1744.”

While the West Lane District School was restored and turned into a small museum by the Ridgefield Garden Club and is now maintained by the Ridgefield Historical Society, the Branchville Schoolhouse has had no purpose other than storage for decades. For a period in the 1940s and 1950s, the Branchville Civic Association used the building for meetings and social events; the organization, led by Americo Ridolfi, had successfully lobbied the town not to sell the building after it closed as a school. The school was a community resource, a gathering place for its neighbors, some of whom still recall social events there.

The Ridgefield Jaycees, a now-defunct organization, used the school for meetings and events during the organization’s active years; founded in 1961, the group disbanded in 1987 as membership shrank due to changing demographics (members had to be 36 or younger). Both the Pony-Colt Baseball organization and the Ridgefield Little League later used the schoolhouse to store equipment, Little League until last year.

The next phase for the Branchville Schoolhouse will showcase Ridgefield’s support for historic preservation and appreciation for the past generations that make this town unique.

The Scott House Journal (SHJ) is a quarterly publication, sharing stories of Ridgefield past. It is written by Sally Sanders, Historical Society Board member and former arts editor