Download PDF

‘Elm-embowered Ridgefield’ — a Gilded Age haven for the wealthy who built their ‘summer cottages’ here

We have our Redding neighbor, Mark Twain (Samuel Clemens) to thank for popularizing “The Gilded Age”: He and co-author Charles Dudley Warner used it to title their 1873 novel about rampant post-Civil War financial excess and corruption. Mark Twain was familiar with the boom and bust of business, having invested enthusiastically but with not much success. By the time he built his own “gilded age” mansion, Stormfield in Redding, in 1908, he had rebounded from bankruptcy but would live only two more years.

The era of explosive growth created the wealth that allowed the owners of railroads, steel companies, petroleum refineries, mines, etc., to establish palatial summer homes in places like Newport, R.I., Long Island, and Lenox, Mass., in the late 19th Century.

While historians put the end of the Gilded Age as the 1890s, when the Panic of 1893 led to the failure of many banks and businesses, the era of great fortunes and great spending continued into the 1920s.

Ridgefield’s “gilded age” began in the post-Civil War period and accelerated into the 20th Century, as wealthy city dwellers increasingly discovered its beauty and healthy air, convenient to New York by a new train line connection. Ridgefield, in turn, recognized the potential of the “summer people” to contribute to the town, both financially and culturally, and town leaders were welcoming to the newcomers.

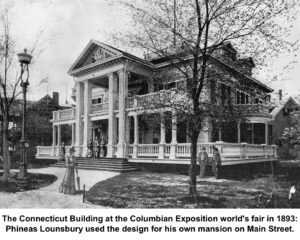

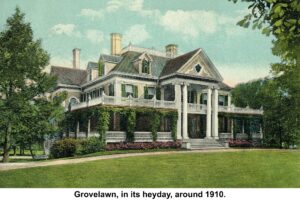

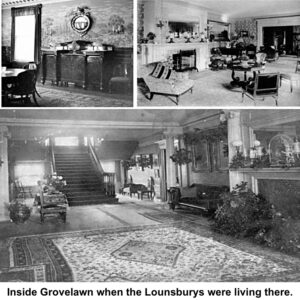

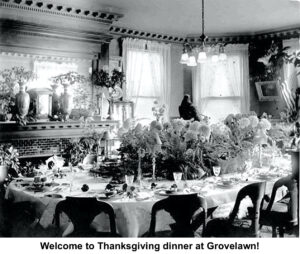

One spectacular house stood out on Main Street as a particular point of pride: Grovelawn, which was built by a native Ridgefielder who had made his fortune in business and banking and served a term as governor of Connecticut (a position his brother would also fill).

The 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, celebrating the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s arrival in the Americas, inspired Phineas C. Lounsbury to create one of the town’s most prominent mansions, modeled after the neoclassical Connecticut pavilion. Completed in 1896, Grovelawn remained in the Lounsbury family until 1945 when the Town of Ridgefield purchased the mansion and surrounding 17.2 acres bounded by Main, Governor and Market Streets and East Ridge Road. The property was dedicated to those who had fought in the just-ended World War II and was named Veterans Memorial Park; the mansion eventually became the Community Center. A beloved gathering place, the building that is now known as Lounsbury House is not only a Ridgefield landmark but a National Historic Site.

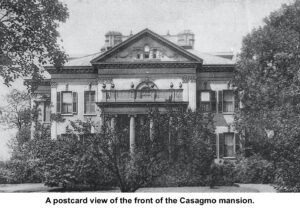

(Interestingly, Gov. Lounsbury’s brother George Lounsbury, also built a home that has status as a landmark in Ridgefield: The Victorian mansion at the southeast corner of Governor Street and East Ridge was for a time a girls school and later the State Police Troop A Barracks. It’s now the Ridgefield Police Department headquarters.)

Not all the grand summer homes have been so carefully preserved or creatively re-used, but in the heyday of Ridgefield as an escape from the city, there were dozens. Writing for the Diamond Jubilee of The Ridgefield Press (in 1950), Elizabeth G. Phillipson (later Nash) quoted New England Magazine’s article, “Ridgefield, the Connecticut Lenox” by H.E. Miller: “Ridgefield has a population of around 2,500, increased by more than 1,000 in the summer. Probably no village in America of equal population represents an equal amount of wealth. It has not the society nor the activity of Lenox, although the summer residence of many society people. It is their desire that the place shall not become too much of a society town; it is already too popular to please some of them.”

Miller went on, “No visitor can fail to be attracted by the homes in Ridgefield, which either from their historic associations or their beauty or taste, are among the important objects of the town. Upon passing the extensive grounds of the RIdgefield Cemetery and entering Main Street from the north, one sees the palatial residence of George M. Olcott, built at a cost of more than $125,000.”

A New York Telegram correspondent, whose piece, “Elm-Embowered Ridgefield,” listed prominent residents, wrote, “Its artistic aspects are falling in the background since it became a retiring spot for millionaires. Mr. Newbold Morris here heads the list. Near his place, which crowns the West Ridge [now called High Ridge], are those of General King and J. Howard King, of Albany; Dr. W.B. Anderton, E.P. Dutton, John A. King (the Peter Parley House), and George Haven Jr. On the East Ridge are the large houses of George Lounsbury, Mrs. Cheesman and Mr. William S. Hawk.

“On the Main Street are the residences of ex-Governor Phineas C. Lounsbury, with grounds like a park, Henry Hawley, D.S. Egleston, Dr. Shaffer and George M. Olcott, of Brooklyn.

“Mr. Morris drives the finest trotters and Dr. Anderton the prettiest cobs. There are several boarding houses here, and if you are anybody, and have letters of introduction, you must join the Ridgefield Club.”

As in Newport, R.I., the Ridgefield summer places were called “cottages,” and none was so large as Downesbury Manor on Florida Hill Road, built in 1901 by Colonel Edward M. Knox, who patterned it after a famous English estate on the Isle of Wight. A 1941 Ridgefield Press article said it had 32 rooms plus 16 “baths” — 46 rooms overall.

The house began life as Bostwyck, apparently a smaller place, built around 1890 by Henry de Bevoise Schenck off the north side of Florida Hill Road. Schenck soon decided he wanted a water view, and built a new mansion, Nydeggen, at Lake Mamanasco (the twin to the old Manresa mansion, it still stands off the end of Christopher Road).

Col. Knox, head of the Knox Hat Company in New York, bought the place, redesigned and enlarged it. Knox had been a second lieutenant in Civil War and earned the Congressional Medal of Honor for heroism at the Battle of Gettysburg at which he was injured.

Knox’s friends included Mark Twain of Redding, who used to visit him at Downesbury Manor. At its peak, the estate was said to be some 300 acres.

Among the special features of the house were tiles surrounding the huge fireplace in the reception room. More than 800 years old, the titles came from the Alhambra, the famous palace/fortress in Spain.

Knox died in 1916 and in the years that followed, there were several owners or lessors of the estate, including a member of the Cartier jewelry family and the Paulist Fathers. In 1941 it was sold to a group that turned the estate, by then 152 acres, into a “dude ranch,” using the manor for accommodations. That lasted a couple of years, but the war probably helped in its demise. It was then proposed as a retirement home for aged physicians, but that odd idea never got off the ground.

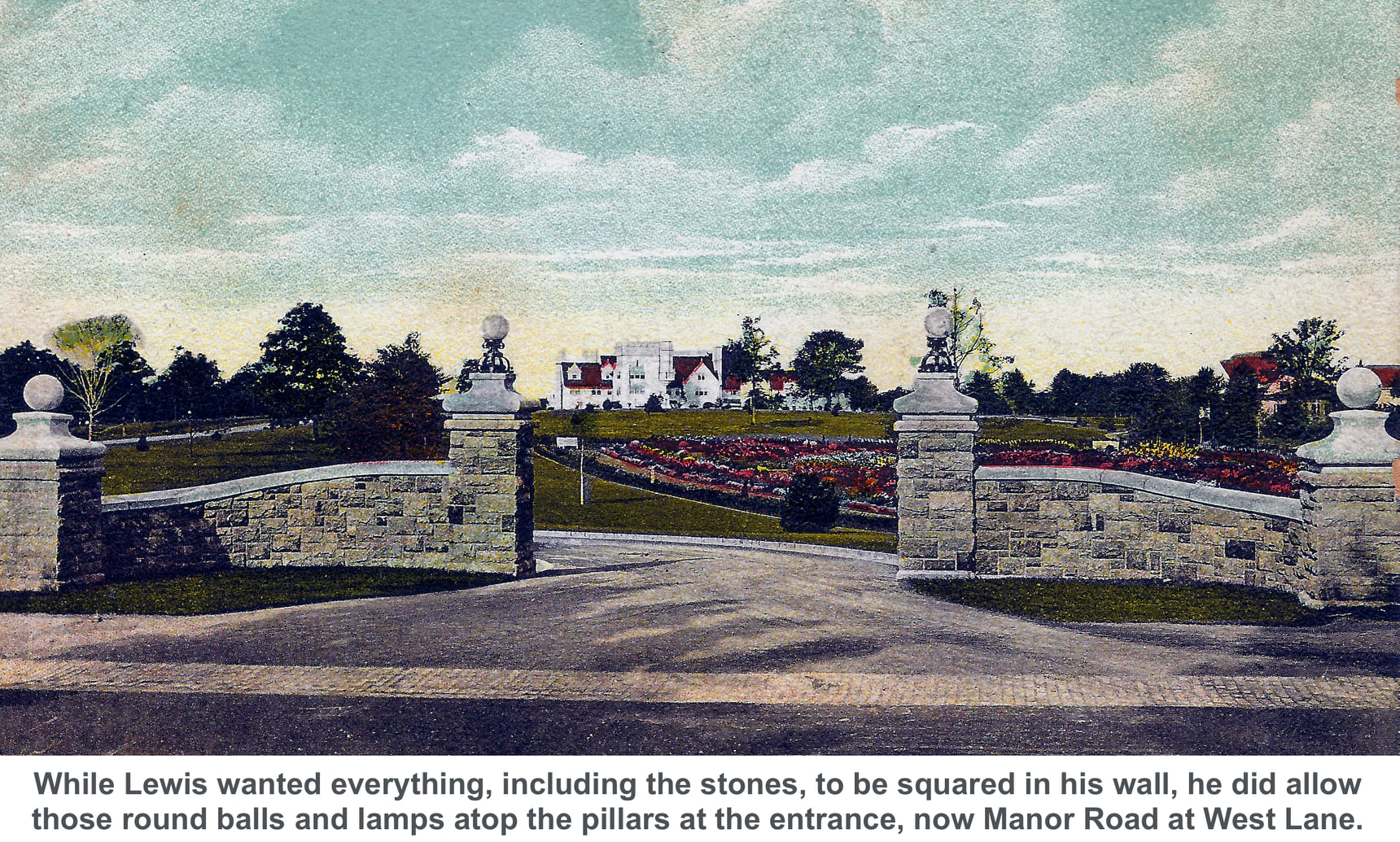

The inability to find anyone who wanted a 46-room house led to its demise in August 1953 when it was torn down. Much of the estate was subdivided, including what’s now the High Valley neighborhood. Many of the great houses in Ridgefield met similar fates during the mid-20th Century. In some cases, their names were preserved, as in Stonecrest, or their owners were recalled in road names as in Lewis Drive in The Ridgefield Manor, which was developed from the Frederic E. Lewis’s estate with its castle-like home, Upagenstit.

Frederic and Mary Lewis had lived in Manhattan and maintained a summer home in Tarrytown for many years, but in 1907, bought H.B. Anderson’s estate on West Lane, west of High Ridge. They replaced Anderson’s house with a new mansion and added more land and many more buildings to what was eventually a 100-acre spread. In 1934, The New York Times reported that the Lewises had spent nearly $2 million on the improvements at Upagenstit.

After it left Lewis family ownership in 1934, it went through a series of owners, at one point even being used as a college, but in 1955 the mansion was razed and the property was subdivided and few now know the name “Upagenstit.”

A name that is familiar to Ridgefielders and recalls a grand home of long standing on Main Street is Ballard: the park land in the village was once the site of the home of Elizabeth Biglow Ballard, whose family had owned it since 1888 and called it Graeloe. The building was once owned by Col. Phillip Burr Bradley, a pillar of the community, who during the Revolutionary War took command of the Fifth Connecticut Regiment — which included many Ridgefielders. He saw action at the Battles of Germantown, Monmouth, and Stony Point and was among the troops who wintered at Valley Forge. He also fought under General Benedict Arnold at the Battle of Ridgefield — virtually in front of his homestead on Main Street.

When she died in 1964 at the age of 87, Mrs. Ballard ordered that her house be torn down so that the property could be used as a park. She felt that Ridgefield already owned an old mansion on Main Street — the Governor Lounsbury House — and that a second mansion would be a burden. Her gardens were preserved and other outbuildings were put to use; housing for the elderly was built on the estate’s backlands and named Ballard Green.

There are many great houses from Ridgefield’s “gilded age” still in private ownership; some have been greatly altered, many look remarkably the same. All are part of the history and future of the town; their builders helped change the town and contributed greatly to the well-being of all its residents.

A girlhood recalled: Early days of the ‘summer people’

Late in life, Mary Clark Hubbell wrote a short reminiscence of her childhood in Ridgefield, which took place just as the Gilded Age was beginning.

She was the daughter of the Rev. Clinton Clark and Mary Merwin Clark; he led the First Congregational Church from 1850 to 1864 and the family lived in the parsonage on Main Street, a little south of the church. Mary, the middle of three girls, was born in 1857; Christina was born in 1855 and Sarah, in 1861.

Written around 1930, Some Children of the Sixties begins, “About seventy years ago three sisters began their lives in a beautiful Connecticut village town. The house where they were born is still standing and has been but little changed in its appearance. It was then the parsonage, for the father of these children was a Congregational minister. His church was near the parsonage. It stood in the middle of the street between the road and the sidewalk, parallel with both.”

The Rev. Clinton Clark was dismissed from his post in April 1864, delivering his final sermon on April 10, but the Clarks’ feelings for the town apparently remained positive. The family remained in Ridgefield for some time, till he had secured a new position. He served as acting minister for the Middlebury Congregational Church until his death in 1871. His body was returned to Ridgefield for burial in what’s now Scott’s Cemetery. A tall monument marks the graves of Clinton Clark and his wife Mary Merwin Clark and two of their daughters, Christina, who died in 1872, and Sarah, who died in 1937.

Mary, who had married James Thaddeus Hubbell in 1888, saw the Gilded Age up close in Norwalk, where her husband served a term as mayor of Norwalk in 1894-95 and was also a state representative for Wilton and judge in the town court.

Norwalk was where financier and railroad tycoon LeGrand Lockwood built his grand Second Empire Style summer home in 1864-68; it’s now the Lockwood-Mathews Mansion Museum. Financial difficulties led to the Lockwoods’ loss of the property in a foreclosure; it was then sold to New York businessman Charles Mathews, whose family lived there until 1938.

Mary Clark Hubbell’s memories of her Ridgefield days were of simple and happy times during a period when Ridgefield (which she called “Ledgefield”) was beginning to attract the summer visitors who would have a great influence on the town’s development.

The Clark girls’ friends included Mary Seymour, whose family lived in the Peter Parley House on High Ridge. Mary Seymour’s father was later appointed Connecticut Railroad Commissioner by Gov. Phineas Lounsbury of Ridgefield, but at the time of Mary Clark Hubbell’s story, he was operating a private school for boys.

“Among our warmest friends,” wrote Mrs. Hubbell, “were the Inn-keeper and his lovely daughter [Abijah Resseguie and Anna Marie Resseguie] … and Phillis their colored cook who was noted for the good food she served and for her pleasant gentle ways.” [To read more about the Clarks and their friendship with Anna Marie Resseguie, read A View from The Inn, The Journal of Anna Marie Resseguie 1851-1867, published by The Keeler Tavern Preservation Society Inc. 1993.]

The “summer residents” had a year-round effect on the Clark sisters’ lives: “As children of the minister, we received many kind attentions. Christmas brought us beautiful gifts, fine dolls dressed in exquisite handmade clothing, toys, tiny bottles of perfumery, and choice candies, which we saw at no other time. I remember especially a dancing-doll worked by the running of sand like an hour-glass. Many of these things came from New York and Philadelphia, where the summer residents had their winter homes.”

The Clark girls and their friends were well aware of the Civil War. Ms. Hubbell described how Ridgefield reacted:

“First to attract our attention to the situation was the local military company marching through the street and stopping near our house to drill. The music of fife and drum, the flags and firearms held conspicuously, impressed us. We heard our elders talk of the war, the victories and defeats….

“Christie and I attended a private school and when Emily and Carrie [friends who summered in Ridgefield] were in the country in term time, they went too. One morning while school was in session, a boy appeared at the door with a yellow envelope for Miss Pickett. After opening it she turned very white, then leaning against her desk, her handkerchief at her eyes, she told us to file out and go home. We ran home as fast as we could, a sense of tragedy upon us. I did not understand it and said to Emily, ‘Why did Miss Pickett cry?’ “Well,’ Emily answered, ‘I guess you would cry if your brother had been killed in the war.’ “ [Sgt. Edwin D. Pickett died July 1, 1863 in the Battle of Gettysburg.]

Among the enduring memories of Ridgefield, Ms. Hubbell recalled an event that occurred shortly before the family moved from Ridgefield. On a morning in April, after her father had left, traveling to a preaching assignment, “…we children were playing in the yard, when a neighbor called across the street, ‘Go in and tell your mother that President Lincoln has been assassinated.’ We rushed in with the message. Mother sank into a chair and wept as though her best friend had died. The pulpit in the church had recently been decorated with flags and bunting on account of northern victories which had ended the cruel war. The next Sunday, our last in Ledgefield [RIdgefield], these decorations were draped with deepest black. A week later in our new home, we saw the same sight, a pulpit with flags in mourning.

“Our first childhood was over, and new experiences were before us, but the Ledgefield [Ridgefield] life held memories which have been enduring.”

Anna Ressiguie’s Sponge Cake

The Scott House Journal (SHJ) is a quarterly publication, sharing stories of Ridgefield past. It is written by Sally Sanders, Historical Society Board member and former arts editor