Remembering Lidia and Quash:

Students memorialize two enslaved Ridgefielders

A solemn ceremony organized by Ridgefield’s eighth grade students will take place on the grounds of the Scott House at Sunset Lane on Tuesday, Nov. 15, at 9:30 a.m. It will be the culmination

The ceremony will be live-streamed and recorded on the RPS Curriculum YouTube channel.

With the assistance of the Ridgefield Historical Society, eighth grade students at East Ridge and Scotts Ridge Middle Schools have been studying records of early life here and learning about how many of the most prominent citizens were also enslavers. While the Town of Ridgefield’s history had been recorded by three prominent residents over the years (Teller, 1878; Rockwell, 1927; Bedini, 1958), it was not until the 21st Century that a book about Ridgefield would tell the story of its African-American residents, both free and enslaved (Uncle Ned’s Mountain, Sanders, 2021).

The Witness Stones Project, which describes itself as “a nonprofit organization whose mission is to restore the history and honor the humanity of the enslaved individuals who helped build our communities,” is collaborating with the Ridgefield Public Schools and the Ridgefield Historical Society to expand teaching of the history of slavery in colonial Connecticut.

The project provides local archival research, professional teacher development, a classroom curriculum, and public programming to help students discover and chronicle the local history of slavery through essays and art. The final component of the work in each community is the placement of Witness Stone Memorials™ that honor enslaved individuals where they lived, worked, or worshiped.

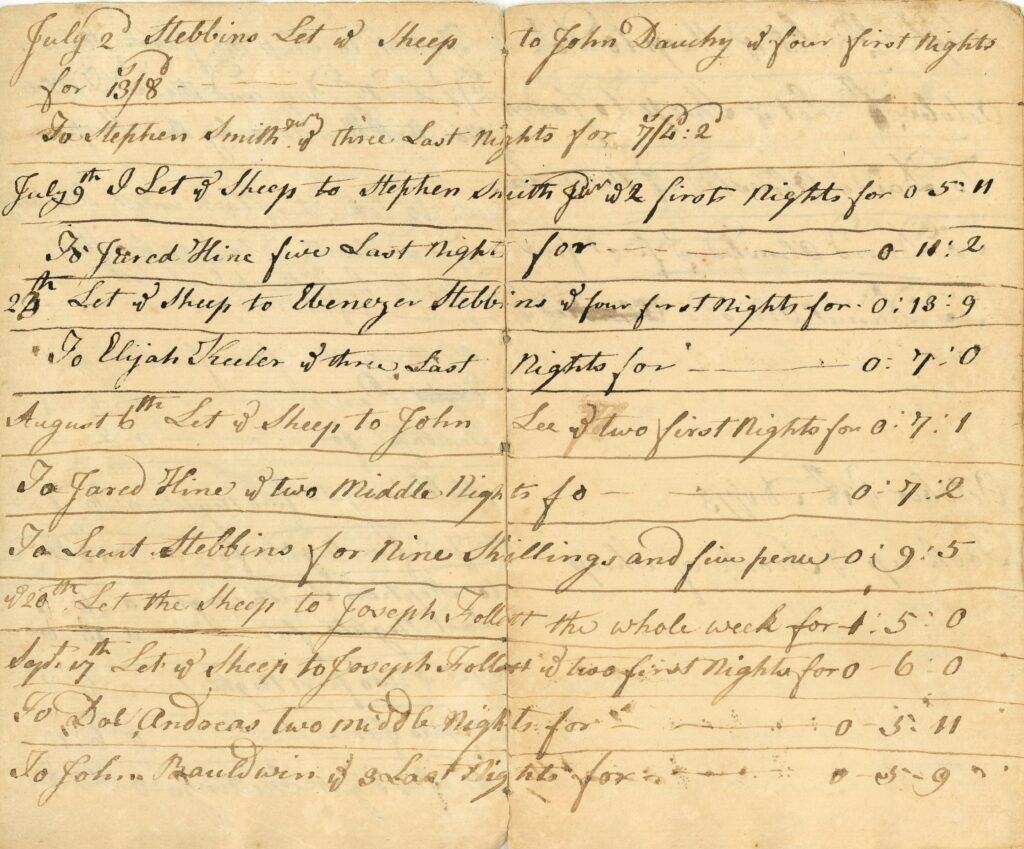

Because the David Scott House, now home to the Ridgefield Historical Society, once housed as many as five enslaved people, it was selected to be the site of the first two Witness Stone Memorials™ in Ridgefield. Although the building is no longer in its original location on Main Street (at the south corner of Catoonah Street), it retains much of its original character as well as what may be drawings created by its enslaved inhabitants. Ancient shingles, which once were the house’s siding, were retrieved by architect David W. Scott when the Scott House was disassembled in 1999 and are now a treasured part of the historical society’s collection. On the smooth interior side of these shingles, which came from the house’s upper floor, are drawings, designs created with what’s believed to have been soapstone. Some of these images are similar to symbols used in West Africa, suggesting a connection to the African Americans who may have been living in that space.

(The head of the American Decorative Arts department at Yale University assessed the drawings as having been done by several different people of varying ages and felt no conclusions could be drawn; a colleague in the department mentioned the connection to adinkra symbols, created by people in Ghana and also associated with African populations in this country. He added, “there is a growing body of scholarship linking similar marks to enslaved people, but the links are sometimes tenuous.”)

Might these shingle drawings have been done by Quash, one of the two Witness Stones subjects? His name connected him to West Africa; its meaning was “born on Sunday.”

The other 2022 Witness Stone will honor Lidia, who lived briefly at the Scott House: at the age of about one, this child was “given” by David Scott to his “son-in-law” Gamaliel Northrop and his wife Mary Dauchy Northrop.

Many questions remain unanswered in the official documents, which is the challenge the students have been dealing with as they create their own versions of the stories of Lidia and Quash.

The Witness Stones Project was inspired by the Stolpersteine project, which began in Germany. German artist Gunter Demnig created Stolpersteine or ‘Stumbling Stones’ to restore the memory of the Jews and others who were murdered by the Nazis The stones are placed in the sidewalk before homes and apartments where people lived in Germany and more than 20 other countries.

With the blessing of the Stolpersteine organization, the Witness Stones Project began in Guilford, Connecticut, in 2017, and became a 501(c)(3) in August 2019. In five years, the Project has partnered with 87 affiliated schools and civic institutions in 46 towns in 5 states. More than 6,600 middle and high school students and their communities have participated in the Project.

When the Ridgefield Witness Stones are unveiled on Nov. 15, it will be at a morning ceremony planned and presented by the students who have undertaken this project. Representatives of the East Ridge and Scotts Ridge eighth grades as well as school system and town officials and Ridgefield Historical Society board members will be present to mark these important additions to the understanding of Ridgefield’s history.

The Witness Stones Memorials™, made of brass, inscribed with what is known about Quash and Lidia, will be placed to be visible to people walking along the Sunset Lane sidewalk by the Scott House. Within Scott House, a special exhibit of the drawings on the ancient shingles, will open Nov. 15 and be on view to visitors through the fall. Andrew Daubar, who designs exhibits for Yale University and lives in Ridgefield, has organized this exhibit.

Mabel Cleves: A Pioneer in Ridgefield Education

Nearly everyone remembers their kindergarten teacher with affection. It takes a special person to guide and appreciate the youngest students.

Among the beloved teachers in Ridgefield’s history, Mabel E. Cleves stood out, and nearly 20 years after she retired from teaching kindergartners in 1938, it was no surprise that the auditorium at the then-new Veterans Park School, built in 1955, was named for her. Nearly 70 years later, some today may wonder who she was as they enter the auditorium at Ridgefield’s oldest elementary school, which has also been the site of some epic town meetings. (But that’s a story for another Journal.)

Born about 1867 in Georgia, Miss Cleves came here in 1898 to teach in Ridgefield’s kindergarten, one of the earlier kindergartens in the United States. Established by Mrs. Peter M. Bryson, the privately funded class was offered at the Center District School, later to become Alexander Hamilton High School, and still later, the Garden School, on Bailey Avenue. The kindergarten was open to all (families had to apply), although limited by space in the number of children who could be accommodated.

Educated at Columbia University, Miss Cleves had training in the Montessori approach, which emphasizes a child-directed learning process, but she also had apparently absorbed the teachings of German educator Friedrich Froebel, who developed the concept of kindergarten and was highly influential in education prior to his death in 1852.

The Ridgefield Historical Society archives include an undated speech given by Miss Cleves on “The Kindergarten,” which extols the work of Froebel. As Miss Cleves described it, “he advocated and earnestly worked for a developing process in education, this is, a process which endeavors to bring into realization and expression all the latent possibilities for good that are within the child.”

The Froebel method focused on three main areas of knowledge: forms of life, forms of mathematics, and forms of beauty, and teachers were integral to the work, guiding the children to explore their world.

After Froebel’s death, his work was carried on by the Baroness Bertha von Marenholtz Bulow Wenderhausen, who was instrumental in spreading the development of kindergartens throughout Europe and in the United States as well. In 1873, Miss Cleves said, there were 42 kindergartens in the United States; by 1898, that number was 4,363. In her speech, she quoted the Baroness, “The most extraordinary progress of the Kindergarten is found in America. The Froebel system is there accepted not only as the foundation of education but also the foundation of instruction. Kindergartens connected with the public school system occupy veritable school palaces. Mothers know and love them. No teachers meeting ever passes over in silence the Kindergarten and Froebel. His method is appreciated and accepted by all from the highest functioning to the humblest rural teacher.”

In describing Dr. Froebel’s kindergartens, Miss Cleves discussed previous observations of childhood learning. Many, she said, “believed in and advocated the early training of the child, but it was left for Froebel to make such early training through a system of purposeful play.” Among the leading thinkers of the time who supported Dr. Froebel’s kindergartens was Dr. William Rainsford, well known in the Ridgefield community for his home, Savin Hill, on the Ridgefield-Lewisboro line (later Le Chateau). Dr. Rainsford’s benefactor was financier J.P. Morgan, a vestryman at St. George’s Church in Manhattan, where Dr. Rainsford was rector.

Miss Cleves quoted Dr. Rainsford as saying “the kindergarten is admitted the best, indeed the only method of reaching children during those years [the years under six] which are now by all authorities admitted to be the most important in their lives.”

In a long passage of her speech, Miss Cleves cited educational experts on the value of kindergarten and made a particular point about the necessity of providing this education to the Black children of the south, quoting an article in Kindergarten Magazine by Mrs. Anna Murray: “The safest and surest way to elevate the people of the race is this, the children.”

The community of kindergarten supporters was apparently facing opposition from cost-cutting school committees, which Miss Cleves sought to counter, citing a survey in Boston. “The kindergarten child has clearer ideas of number form and color; greater knowledge of and interest in nature; improved singing; better expression in reading, improved articulation, more orderly and careful arrangement of material in busy work and greater manual skill, shown especially in writing and drawing. …Kindergarten children are neater, cleaner, more orderly, more industrious and more persevering. They are also more self-reliant, more painstaking, and more self-helpful. They are less self-conscious and more polite. They obey more quickly and are more gentle to each other. They have a more developed spirit of helpfulness, they are more eager, alert and responsive. They are interested in a wider range of subjects. They have finer sensibilities.”

Her goal was to push back against the critics who said kindergarten was just a place for play. “Would thousands of the most intelligent young women of our country — many of them college graduates, devote from two to three years to the kindergarten system — and then go forth to spend years of work in its interest — if the kindergarten was simply a place for the amusement of children?” she asked.

In her conclusion, Miss Cleves told her audience, “Friends — underlying this play of the kindergarten is a deep earnest purpose, which permeates every phase of the work — games, plays, stories and occupations: a purpose which has as its aim the training of your children, body, mind and soul; a purpose for the carrying out of which serves to the interests of this country thousands of little children every year.”

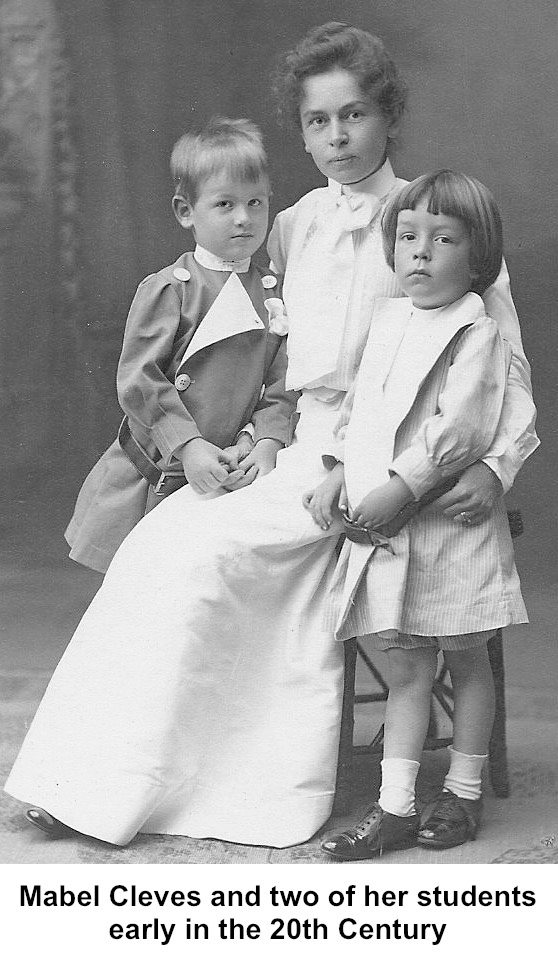

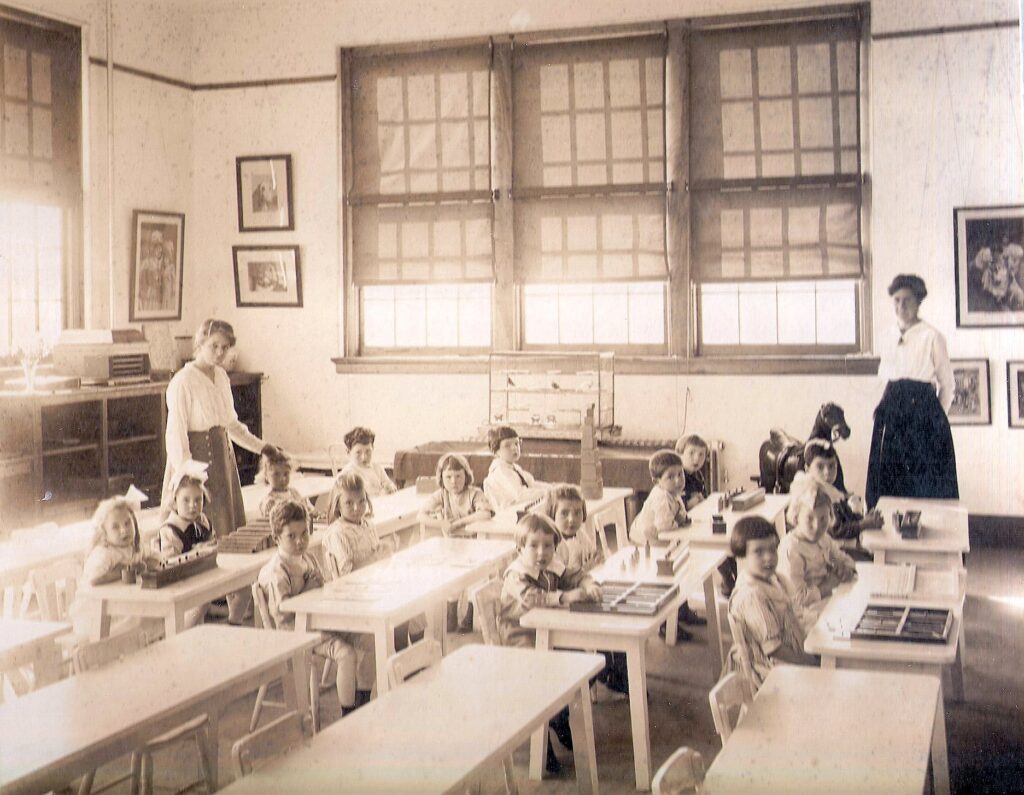

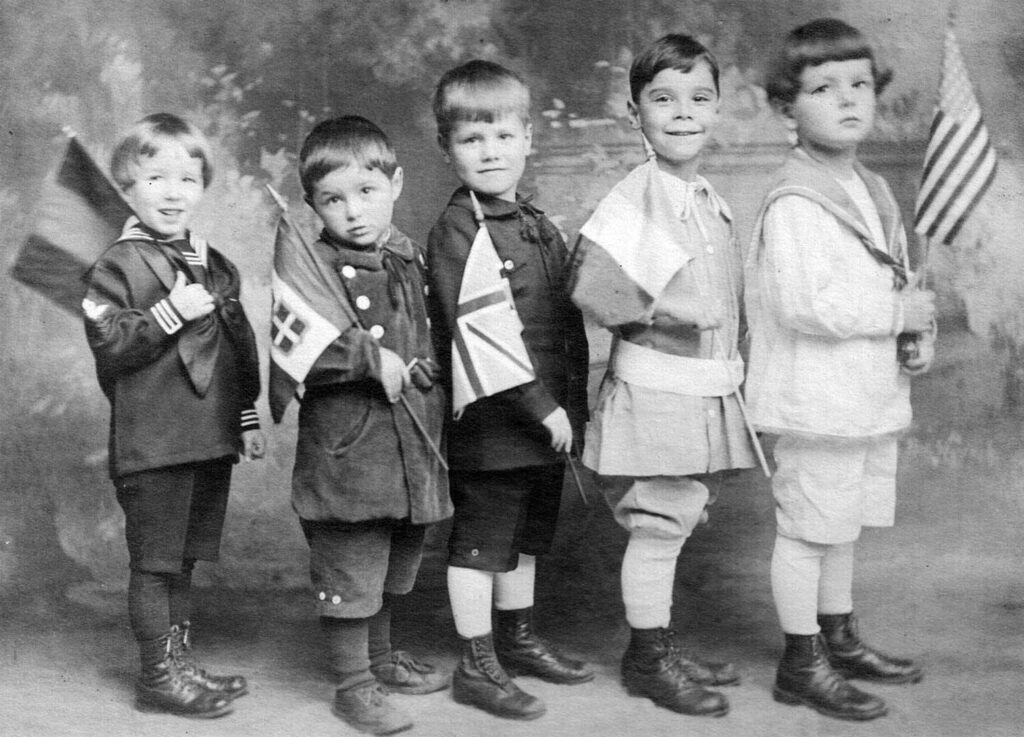

Miss Cleves’ affection for her students is obvious in the photos of her with them; in the Ridgefield Historical Society collection are several, including images from her early days of teaching to one taken a few years before she retired in 1938. Miss Cleves’ work with her young pupils was not her only contribution to education in Ridgefield: She was also a leader in the effort to build a modern school in Ridgefield, which was then served by district schools (generally one-room, multi-grade, single teacher). As part of the dedication book published on the 1914 cornerstone laying of the Benjamin Franklin Grammar School, an imposing brick edifice on East Ridge that later (with additions) became the Ridgefield High School, Miss Cleves wrote an account of the work that preceded the new school.

Quoting from a 1903 Ridgefield Press, Miss Cleves wrote: “Parents who love their children want them educated. When they come to Ridgefield to investigate the town as a place for a home, they ask first for our schools. They are pleased with our healthful situation, our beautiful homes and well kept grounds; our handsome streets; our water supply; our fire department, etc., but these cannot outweigh the disadvantages of the lack of a better class of schools.”

The campaign to build a modern school and raise educational standards in Ridgefield was on its way with the involvement of the Woman’s Club, which was organized in 1903 under the aegis of Mrs. A.H. Storer. It took until the annual town meeting of 1912 to achieve the reformers’ goal, thanks to the private donations that helped acquire the East Ridge land. With 108 women recently made voters, the town meeting accepted the site and bonded the town for $40,000 to “erect a school building that would be a lasting honor to the town of Ridgefield.”

In the interval, the Center School was so overcrowded that the kindergarten had to be moved to St. Stephen’s Parish House and later Center School pupils were educated in temporary space in the Town Hall.

When Miss Cleves brought her kindergarten class to the new school, she made sure that her pupils had the sunniest room, in the building’s southwest corner where the large windows provided natural light and fresh air. In the years that followed, the kindergarten would once again be back in the Center School, renamed the Garden School, until the town built Veterans Park School, which opened in 1955.

Although it had been nearly 20 years since she retired, and several years since her death at the age of 85, Miss Cleves was well remembered. “She had a remarkable gift for teaching very young children, and she truly can be called ‘a legend in her own time,’” her friend, John White, wrote in The Ridgefield Press 1990.

In addition to her teaching, Miss Cleves also founded the town’s first PTA in 1901, which for its first 15 years was called The Mothers Club. Her pupils, three generations of them during her 40-year career, knew her kindness outside the classroom as well.

“She had a permanent arrangement with Ryan’s Country Store [on Main Street] to buy shoes or clothing for needy children in her classes,” White said. “There were many poor students in her class. She always shared her meager salary in this way.”

And, John White recalled, Miss Cleves told them tales. “As a storyteller to children, Miss Cleves was long without a peer in Ridgefield,” The Ridgefield Press reported. “She told stories not only in her kindergarten classes but on Saturday mornings at the Ridgefield Library.”

For 40 years, Miss Cleves was the companion of May Rockwell, who owned the “House of Friends,” a boarding house for teachers, writers, musicians, and others of an intellectual or artistic bent, on Governor Street. (The building, formerly the home of Gov. Phineas Lounsbury, had been turned into offices years ago and was torn down in 2015 to make way for the RVNAhealth headquarters.) Miss Cleves lived there most of her years in Ridgefield, though later in retirement life, she enjoyed wintering in Florida.

Her pioneering work in Ridgefield education is honored, both at Veterans Park School and in the archives of the Ridgefield Historical Society.

The Scott House Journal (SHJ) is a quarterly publication, sharing stories of Ridgefield past. It is written by Sally Sanders, Historical Society Board member and former arts editor