African-Americans in 20th-Century Ridgefield suffered at the hands of local racists and those who were simply insensitive to their prejudiced practices. The pages of the Ridgefield Press contained stories of several outstanding examples: An African-American beaten up by a drunken white man outside the town hall, the burning of a cross on the front lawn of a racially mixed couple, and the problems faced by an African-American celebrity who moved to Ridgefield.

Press coverage also featured a man of peace, an African-American minister who spent much of his life fighting racial injustice.

The Beating of a Black Man

One of the most blatant cases of racism to appear in the pages of the Press occurred Sept. 30, 1922, and led to cries of injustice and to some embarrassing publicity for the local state police.

That evening, Robert Cooper had just finished eating at Coleman’s Lunch, a small diner behind the town hall, and was chatting with James “Gus” Venus, the counterman. Cooper was a black chauffeur for a woman who had homes in North Salem and in New York City, and was a frequent visitor to Ridgefield. “He bears an excellent reputation as a peaceful, inoffensive person,” the Press said. Thomas Kelly came into the restaurant, saw Cooper and immediately ordered him to leave, “saying he would not eat with n—-s,” the Press reported. Cooper apparently ignored the demand and Kelly “then struck the colored man a severe blow in the face and followed him out to Main Street, and struck and knocked him down and kicked him.” Bystanders rescued Cooper and brought him to Charles Riedinger’s electrical shop on Bailey Avenue. “Kelly followed and with difficulty was restrained from renewing the assault,” the newspaper said. Cooper “bled profusely” and was taken to Dr. B. A. Bryon’s office on Main Street (where the CVS shopping center is today). “He was severely injured and is very likely to lose the sight of one eye,” the Press account said.

One of the witnesses to the attack was seven-year-old Richard E. Venus (who was at Coleman’s Lunch getting a hamburger from his older brother, Gus, the counterman). Dick Venus grew up to become Ridgefield’s postmaster, a selectman, and its first town historian.

Venus also wrote 366 historical columns in the Press and in one in 1983 describing Coleman’s diner, he said: “The little lunch wagon was the scene of so many happy and pleasant memories that it is sad to report that it was here that I witnessed the only act of racial prejudice that I have ever encountered in Ridgefield. A white man, from a well-known Ridgefield family, had apparently imbibed too much alcohol and refused to sit at the counter with a black man who was passing through town.

“The white man was both verbally and physically abusive. The whole affair was quite sickening. Finally the State Police were called and he was placed under arrest. It made an impression that I will never forget.”

The “well-known Ridgefield family” included Sgt. John C. Kelly, commander of the local State Police barracks, brother of Thomas Kelly.

David W. Workman, the editor of the Press, was irate over the incident. The Press offices were in the Masonic Hall building, just south of town hall and spitting distance from Coleman’s Lunch; it’s possible someone on the staff witnessed at least some of the incident.

“AN INVESTIGATION NEEDED,” said the bold, front-page headline over an account of the assault that was as much an editorial as it was a news story. Workman’s article pointed out several disturbing facts.

“Roswell Dingee, a constable, was present at the time of the assault or immediately after, but made no attempt to arrest Kelly,” Workman wrote. This is the same constable that had been involved in other controversial incidents such as arresting a man for drunk driving when he himself was drunk.

Thomas Kelly had disappeared for a few days. When he returned, state police arrested him for assault and breach of the peace, and brought him before Justice Samuel Nicholas in the town court. “On the statement of the state policeman, a nominal fine was imposed on Kelly,” the Press said. That fine was a $15 fine plus court costs.

“Neither Michael Coleman nor the doctor nor any of the witnesses were subpoenaed or called to testify as to the nature of the assault or the severity of the injuries to the colored man,” Workman wrote. “The justice had only the statement of the State Police to guide him in imposing punishment.”

Editor Workman minced no words. “A brutal bully makes a most atrocious attack on an inoffensive peaceful man of good reputation, simply because he is a colored man, and he goes unpunished in this town,” he wrote. “The state police take charge of the arrest and punishment of the bully and do not call Mr. Coleman or the doctor or any of the witnesses to testify to the assault or the seriousness of the crime so that the justice may know what punishment to inflict.”

Workman then pointed out that “Thomas Kelly is a brother of John C. Kelly, head of the State Police in this town. Are relatives of the State Police exempt from punishment for crimes?

Apparently an investigation should be made by those who appoint and control the State Police.”

The fallout from the incident produced both positive and, apparently, negative results. On the negative side, the store of Charles Riedinger was broken into a few days later and, according to one account, “some goods taken, and other goods damaged so as to destroy their value.”

An anonymous Ridgefielder, who saw the burglary and vandalism as “vindictiveness” for Riedinger’s helping out the injured black man, sent the merchant a check for $100 (equal to around $1,400 today). “Every man and woman in Ridgefield must admit some responsibility for the town conditions,” the donor said. “I thus feel that we should bear some share of your loss.” The donor asked the Riedingers to accept the $100 “not as a gift, but as a share of your loss. I hope steps will be taken to bring those who are responsible for the Town Government, whether holding office or not, to some realization of the damage done to the standing, and therefore, the prosperity of the town.”

At the same time, the Press continued its criticism of the state police, saying, “It is unfortunate that those guilty of the crime above mentioned have not been found and punished. We hear that the State Police neglected to take any fingerprints. This would seem gross neglect. We hope it is not true.”

Meanwhile, the Press’s Oct. 17 call for an investigation was having results. By December, 18 Ridgefield women, upset at the apparent mishandling of the Cooper case, petitioned Connecticut Governor Everett J. Lake, demanding an investigation. “We make no criticisms of the present head of the [State Police] Department situated in Ridgefield, but we feel that it is imperative that we should have in this position [the investigator], an outsider, a man with no local affiliations, and of an age to command respect from his authority. We respectfully request that some higher official be delegated to come here and make an investigation.” Governor Lake thanked “the good women of Ridgefield” and immediately passed the buck to Robert T. Hurley, the superintendent — equivalent of chief — of the Connecticut State Police. Hurley wrote the petitioners, saying, “The complaint will be fully investigated.” He asked to meet with them “and any other citizens who may be able to throw light on the matter.” The petitioners were not pleased with the response. They hired Attorney William Jerome.

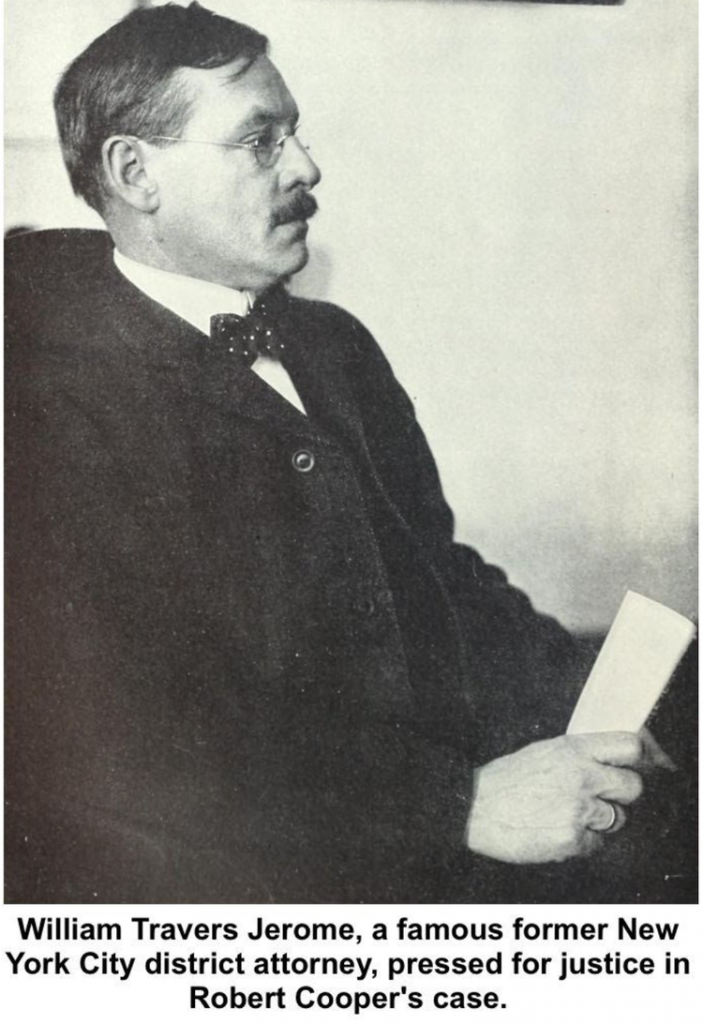

William Travers Jerome (1858-1934) was no ordinary lawyer. Based in New York City, he had been a prominent district attorney in the city and “a man of wide experience and of the highest reputation in his profession,” his clients said.

Indeed, DA Jerome was famous for heading campaigns against political corruption and mob bosses, even personally leading raids on the criminals. In his most famous case, he prosecuted millionaire Harry Kendall Thaw for the murder of the noted architect Stanford White, who had been having an affair with Thaw’s chorus-girl wife. (Thaw was found not guilty by reason of insanity and sent to an asylum.) Jerome’s first cousin was Jennie Jerome, who was the mother of Sir Winston Churchill, the British Prime Minister.

Jerome told Superintendent Hurley he was hired because of “an apparently gross miscarriage of justice and grave dereliction of public duty in connection with the brutal assault committed in Ridgefield, by one Thomas Kelly, upon an inoffensive colored man.” He objected to Hurley’s reply that he would meet with the women about the facts in the case, saying they clearly had no personal knowledge of the facts and that the reason they petitioned was to have someone in high authority determine those facts.

“It seems to them that your request for a conference at the town hall was merely camouflage,” he wrote. “They fancy that such a conference was designed only to humiliate them and to avoid making a real investigation which it seems to them it is your duty to make and for doing your duty the taxpayers pay you. Some are unkind enough to refer to an old saying that ‘you don’t hunt ducks with a brass band,’ and to intimate that the best way to collect evidence of criminal acts is not by meetings and discussions with the police authorities in the town hall.”

Jerome added, “Let me submit, that however unfair my clients may seem to you in these thoughts, the charge is a grave one and involves a serious dereliction of duty unless it be exhaustively investigated.”

Hurley was not pleased, either. “My first impulse on reading the more unreasonable portions of your letter was to make a categorical denial of all the principal facts,” he wrote Jerome in late December. “The department, however, prides itself on its unquestioned reputation and welcomes all fair-minded criticism. I am ready to take for granted the good faith of your clients, whatever their feelings towards me in this connection may be, and I feel sure that once I have clearly before me just what it is that these good people take issue with, that I can remove the misunderstanding.”

“I personally have been satisfied as to the facts alluded to in the editorial,” he said, without comment on whether he found the “facts” correct.

Hurley told Jerome that he had met with “many Ridgefield citizens” interested in the case, but none were apparently petitioners. He again asked that the 18 identify themselves.

In March Jerome noted that he was aware the department has sent “special representatives” to Ridgefield and felt that by now they should have been able to “fully ascertain the facts in this case.”

He was now representing 16 of the women signers to the petition to the governor, as well as “two men who are large taxpayers of Ridgefield and who also as officers of the Ridgefield Protective Society.” The society, he said, consisted of “a large number of other owners of property at Ridgefield.” They’d even hired a detective agency to look into the case, “at considerable expense.”

He continued:

“As chief of a police organization, you are, or should be familiar with the criminal law of Connecticut and should know that a case of assault such as that which resulted in the petition which the governor referred to you, calls for a decision that would recognize the crime more nearly as a felony than as simply disorderly conduct. The trial at Ridgefield, however, resulted in only a fine of $15 and costs being imposed on the party charged with the crime. The lightness of this penalty as compared with the facts shown above in affidavits readily secured by a competent detective agency (and equally available to your men) suggests that in prosecuting this case, the local representatives of the state police at Ridgefield neglected to properly collect the evidence and adequately present it at trial. Whether this was due to incompetence, or intention in order to protect someone having political or other influence, it justifies anxiety on the part of Ridgefield residents as in whether they can count upon competent and impartial protection against crime.”

The April 3, 1923, Press contains the last mention of the case, and no other records of what finally happened have been found. Hurley clearly investigated the charges that the case was mishandled, and if he found any fault, he may have dealt with it internally. However, it appears that Sgt. John Kelly was not blamed, for he continued to lead the local barracks and eventually rose through the ranks to hold Hurley’s job — head of the entire state police force. It may well be that, because of his relation to Thomas Kelly, John Kelly had abstained from any involvement in the investigation and arrest, and that the unnamed state policeman who did handle the case got some blame for mishandling — possibly because he thought that a light prosecution of his boss’s brother would please Sgt. Kelly.

It’s interesting to note that immediately after the Press’s outraged call for an investigation, Press coverage of state police matters seemed to dry up. But within a couple months, stories of police actions began becoming commonplace again. What’s more, some of the stories seemed to go out of their way to praise Sgt. Kelly for his work.

A Burned Cross for Christmas

Another case of racism gained national attention and wound up with the rare prosecution of the racist in both state and federal courts.

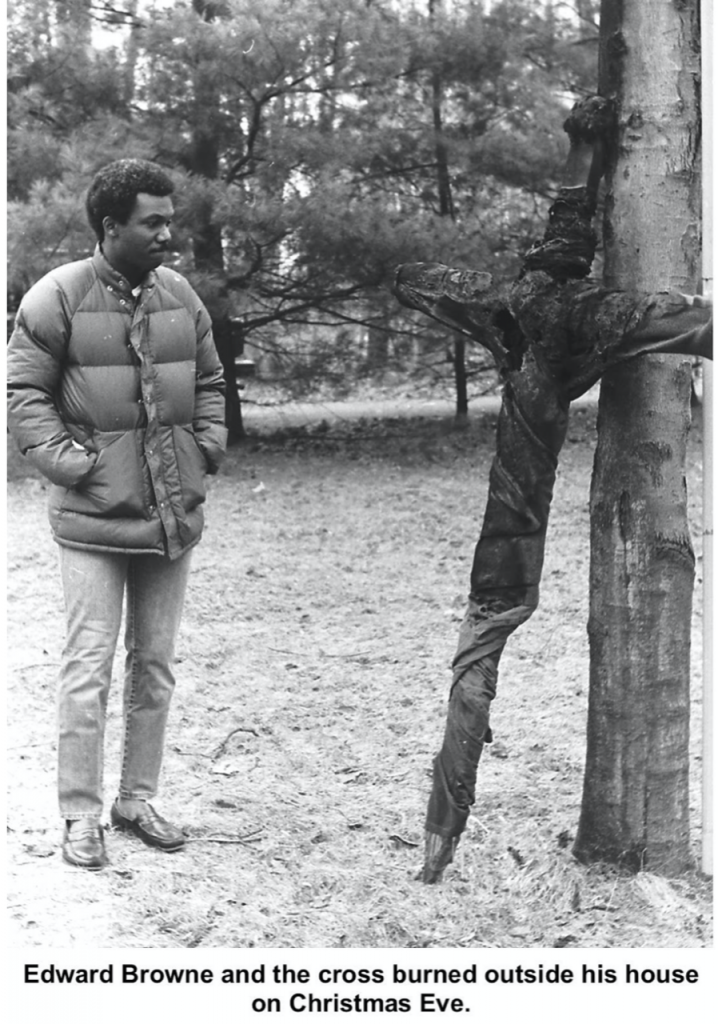

Two nights before Christmas in 1978, Edward Browne, his wife, and their two children were baking Christmas cookies and singing carols as they prepared for the holiday. At around midnight, Mrs. Browne noticed a glow coming through a front window of their Old Sib Road home. She looked out and saw a six-foot-high cross burning on their front lawn. For Mr.

Browne, who is black, and his wife, who is white, it was a frightening experience. For Ridgefield, the cross-burning shocked a community where only about 50 of its 20,000 residents were black. It led to years of litigation, including the involvement of a man who is now one of Connecticut’s U.S. senators.

“We’re afraid to go out at night and we’re all practically sleeping in the same room,” Edward Browne told a reporter two days after the cross-burning. He was barricading the doors at night, and leaving many lights lit.

Browne, who was 35 at the time, was an executive recruiter who had moved to town six months earlier. He said the family found Ridgefield charming and the people they met were friendly. And in interviews after the event, he never expressed anger at the community, only at those who had burned the cross. At the outset, he was not even sure of the motive.

“It’s easy to say that it is racial because I’m black living in a white neighborhood,” he told the News-Times in Danbury. “But it could have been a prank. It was a sick person, no matter whether he is black or white. He has a lot of hatred. Not only that, he is a coward.”

Ridgefield police began an investigation immediately. But by mid-January 1979, no suspects had been arrested, and the Brownes were becoming anxious.

“Time is running out for the police,” Browne said, adding that if the local police didn’t act, he might seek state or federal assistance. The cross-burning was having “a terrible psychological effect” on his family, he said.

By then, he suspected that an adult was responsible. “I think this is somebody with some hatred, and some really ugly motive was behind this,” he told the Hartford Courant Jan. 13.

He was right about the hatred and the motive.

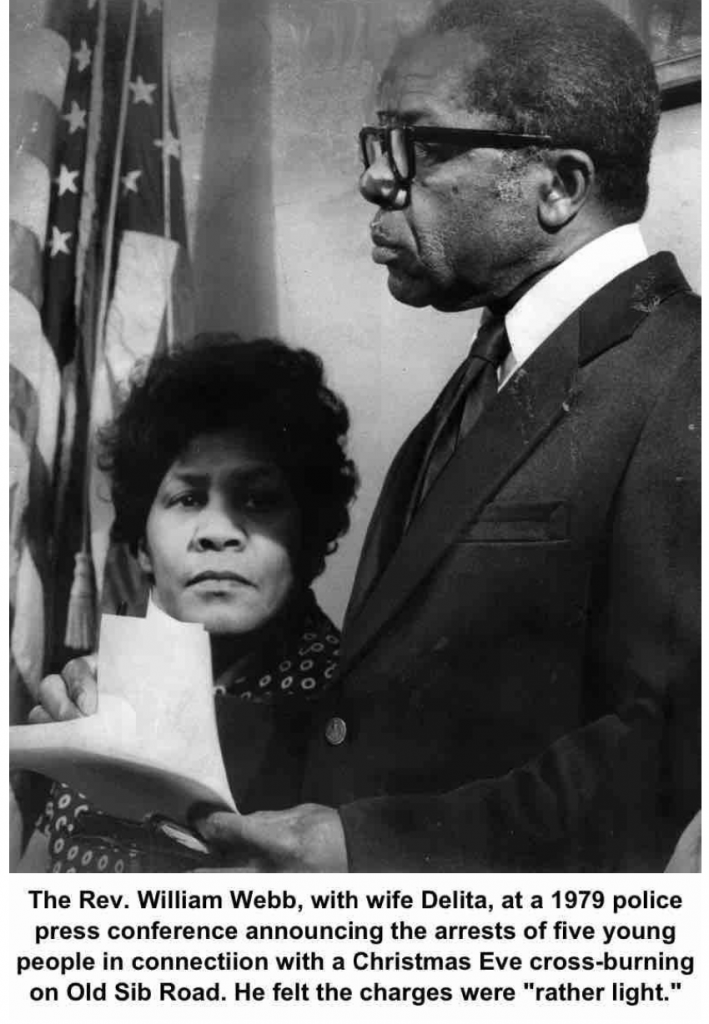

On Jan. 24, Police Chief Thomas Rotunda called a press conference to announce the arrest of five young men, aged 15 to 20, who were charged with criminal mischief in the third degree and disorderly conduct, both misdemeanors. The five came from Ridgefield, Bethel, Danbury and New Fairfield.

One of the five, a Ridgefield 18-year-old, was the self-admitted ringleader of the group. He later told The Ridgefield Press, “I hate blacks.”

In 1951, Ridgefield had become one of the few towns in Connecticut to have its own chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Over the years, the chapter had had as many as 200 members, most of them white. The chapter was formed to make the community more aware of the existence of a local black community and the problems it faced, including lack of affordable housing. The group had been active in the town, usually working behind the scenes to deal with any racial problems. Its members were vocal on many issues, and, oddly enough, the chapter was among the first organizations to publicly support a new Ridgefield police headquarters.

William Webb, the chapter’s first president, went on to become president of the Connecticut NAACP, and a minister.

When the arrests were made, NAACP officials were relieved that an action had been taken, but weren’t pleased with the charges, which seemed extraordinarily mild for a deed so vile. Bernard Fisher, then president of the Connecticut NAACP, and Webb, still head of the Ridgefield branch, also appeared at the police news conference. While they thanked the police for their work, they criticized the charges.

“All this is, is a slap on the wrist,” Fisher said.

The charges, it turned out, were not selected by the police, but by the man who would prosecute them in the Superior Court in Danbury, State’s Attorney Walter Flanagan. “They were the charges we felt appropriate to the offense,” Flanagan said later.

While police reported the five defendants claimed the cross-burning was “just a prank,” Browne told The New York Times, “I don’t consider this to be a prank. I think of it this way: If somebody burns a cross in front of my house, it has a lot of definite meanings. It means ‘get out’ or something else.”

By late February, Browne was reporting harassing phone calls and notes. He estimated the callers were 22 to 30 years old, and usually threatened to burn down the Brownes’ house, told them to get out of town, and offered “a lot of profanity, racial jargon, and rhetoric.”

“I’m not scared, but it’s just a pain, a distraction, and an inconvenience,” he told Burt Kearns, a reporter for the Press. “It could have been a handful of people out there who are out-and-out racists who decided that they were going to do something about this,” he theorized. “The fact that I’m in an interracial marriage is bound to annoy people, and they have the right to think the way they want. But when they take that thinking and start to invade on my privacy, they ought to be dealt with seriously.”

“I’m the wrong person to do this to,” he added. “I’ll find them, and I’ll deal with them. They’ll be facing federal charges. I’ve got two-by-fours across the doors, a security system and more lights outside. I’m basically prepared to defend myself.” Was he carrying a gun? Kearns asked.

“I’m prepared for any intruders,” Browne replied.

In April Browne complained to the office of U.S. Attorney Richard Blumenthal, now a U.S. senator from Connecticut, that the cross-burning had violated his civil rights under federal law. Blumenthal asked the Federal Bureau of Investigation to look into the case to see if federal charges should be lodged against the five. There had been allegations that the Ku Klux Klan or some similar organization may have been involved, which also prompted a representative of the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to visit Ridgefield to find out if racial discrimination was being practiced in town.

In May, the ringleader pleaded “no contest” to a charge of disorderly conduct in Superior Court, and was sentenced to 30 days in jail on that charge. (He was also sentenced to an additional eight months for reckless endangerment in an unrelated case in which a van he was driving hit a 13-year-old pedestrian.) The third-degree criminal mischief charge was dropped.

The 20-year-old was also sentenced to 30 days. Two 17-year-olds were handled as youthful offenders, which meant actions in their cases would not be made public. The 15-year-old was turned over to Juvenile Court authorities.

Then in late September, U.S. Attorney Blumenthal announced that a federal grand jury had indicted the ringleader, by then 19 years old, on charges of “intimidating and interfering with a family” by burning a cross in front of their house “because of their race and color, and because they were occupying and enjoying that dwelling.” The charges were a violation of U.S. Code 42, The Fair Housing Act, under a subsection that makes it a misdemeanor for anyone who “by force or threat of force willfully injures, intimidates or interferes with, or attempts to injure, intimidate or interfere with any person because of his race, color, religion, sex, handicap…, familial status …, or national origin and because he is or has been selling, purchasing, renting, financing, occupying, or contracting or negotiating for the sale, purchase, rental, financing or occupation of any dwelling…” It was the first time such an action had ever been pressed in Connecticut.

Blumenthal said the federal charge was warranted because of “all the circumstances of the alleged offense, …the impact on the Browne family, and the possible deterrent effect of prosecution.” He would not comment on why the other four involved in the cross-burning were not being prosecuted.

Ben Andrews, executive director of the state NAACP, welcomed the charges. “It’s hard to speak in terms of satisfaction with something of this nature, but I think it is appropriate,” he said, adding that he was concerned about the increase in racial incidents in the area, and noting that Ku Klux Klan literature had recently been distributed in Danbury.

With respect to the cross-burning, there was no question about the ringleader’s feelings. He described his participation in a June interview with Kearns (who later became a news producer for WNBC-TV, and managing editor of the TV shows Hard Copy and A Current Affair), and fellow Press reporter Larry Fossi (later a prominent attorney in New York City).

The 19-year-old confessed that he had planned the cross-burning because he didn’t like having Browne in his neighborhood. “I hate blacks,” he said. “I’m prejudiced. I didn’t even know that his wife was white until I read it in the paper. I had just seen him around.” He had already built the cross that he planned to burn that Halloween at the Brownes’ home, but dropped the plan because there’d be too many people out at night.

According to information Kearns uncovered, four of the five had spent an evening of hard drinking at the Scorpio Lounge in Danbury when the ringleader, complaining about his black neighbor, suggested burning the cross that he had already made. He stopped at his mother’s house, siphoned gas from her car, wrapped the wood in rags, drove to the Browne house, soaked the cross, and ignited it.

“Flames leapt up four to five feet higher than the top of the six-foot cross,” according to a federal court record. “It was a spectacular, frightening sight,” the transcript said, so frightening, in fact, that the driver in the group—described as a high school dropout—took off in the car, leaving the ringleader and another boy behind. However, he soon thought better of it, and returned to pick the two up.

The case was tried in Federal District Court in Bridgeport in May 1980. On May 19, the jury returned a verdict of guilty. Judge T.F. Gilroy Daly sentenced the ringleader to a year in prison, but suspended the imprisonment and placed him on probation for three years, with the condition “that he enter into a vocational training program and an alcohol treatment program under the supervision of the United States Probation Department.”

Despite the seeming leniency of the sentence, the ringleader appealed, using a public defender, who argued among other things that the government had failed to prove that the cross-burning intended to interfere with the Brownes’ federally protected right to occupy their home, and that the federal government had been “vindictive” in prosecuting the accused on another misdemeanor charge after the state had already successfully done so.

However, in December of that year, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit affirmed the District Court’s decision. Thus, the ringleader had a rare and unsavory claim to fame: He was the only Ridgefielder ever convicted in two separate courts, state and federal, for one illegal act.

Green and White

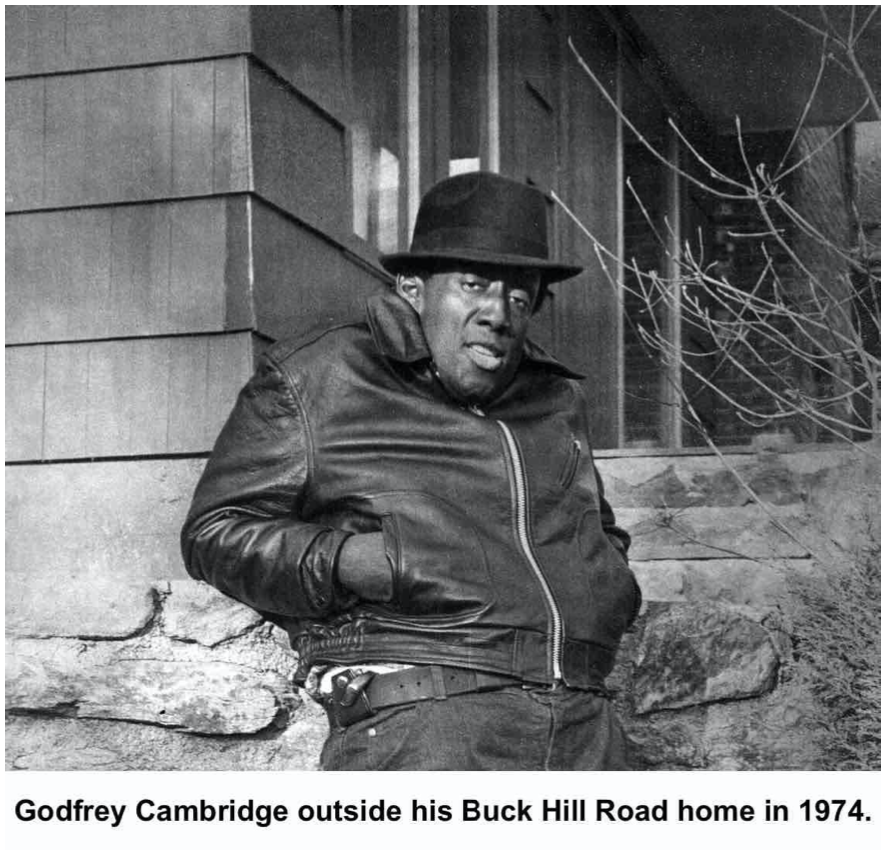

When actor-comedian Godfrey Cambridge moved to Buck Hill Road in 1974, he called his new 14-room home his “dream house.” Within weeks, it was his nightmare. The year that followed was full of charges and counter-charges that made national news.

Raised in Harlem, Cambridge graduated from Hofstra College on Long Island in 1955 and worked as an airplane wing cleaner, judo instructor, ambulance driver, and cabbie to earn money while trying to break into acting. His first paying role — at $15 a week — was in a 1956 off-Broadway show in which he played a bartender. By 1961 he had won an Obie for Best Performer for his role in “The Blacks,” Jean Genet’s drama about racial hatred.

He soon turned to films, often comedies but also dramas, and appeared in 15 of them. Once he had made a name for himself, he insisted that his roles depict him “as a man, rather than as a Negro.”

Godfrey Cambridge was drawn to Ridgefield for its schools and its “country” atmosphere.

But in March 1975, he took three local real estate agents before the State Real Estate Commission, charging they had misrepresented the condition of the house they sold him. His most oft-quoted example was the day his foot went through the living room floor. Promised repairs were not done before they moved in, he charged. He testified that he paid $125,000 for the house (about $650,000 in 2020 dollars) and then had to sink another $100,000 ($500,000) into bringing it up to standard.

Of 12 allegations brought by Cambridge and his wife, the commission dismissed 10. However, the commission did rule that the house was incorrectly described as having a full basement, and that the Cambridges were misled into thinking all the flooring was hardwood. The commission eventually suspended the agents’ licenses for 60 days, although the agents vehemently maintained the Cambridges had known part of the house had a half-basement, and some rooms had plywood flooring.

Many national news stories portrayed the real estate case as a rich white town against a black newcomer. Cambridge never charged that the complaint involved racial motives. In fact, he told the New York Times there were no racial overtones. “Money is where it’s at,” he said.

“Black and white? Forget that. It’s green and white.”

However, soon after the real estate clash, Cambridge was battling Ridgefield’s town government, which maintained that he had erected a chain-link fence too close to the road, creating problems for snow plows. Cambridge said the fence was needed to protect his family from harassment and his property from vandals, but he eventually moved it.

Indeed, all the publicity over the real estate case may have stirred up area racists. Cambridge charged that, because of racial prejudice, his property had been vandalized, his wife was nearly run off the road in her car, and his teenage daughter had been threatened not to attend a school dance. The police investigated, but were never able to arrest anyone.

By late 1976, relations between the actor and the town had quieted down. Then, suddenly, on Nov. 29, Cambridge suffered a heart attack and died. He was on the Burbank, California, movie set where he was playing Ugandan dictator Idi Amin for an ABC TV film, “Victory at Entebbe.” He was only 43.

Newspapers reported Cambridge was often overweight and it was speculated that his habit of “yo-yo dieting” might have been a factor in his early death. He had weighed some 300 pounds in the early 70s, but had lost 170 pounds by the time he bought the Ridgefield house.

Amin himself later declared that Cambridge’s death “is a good example of punishment by God” since he was involved in a “fictitious film on the invasion of Uganda by Israel because God knows the invasion was wrong.” Amin, who called himself dictator for life, was later overthrown, fled Uganda and died in exile.

Cambridge’s family eventually abandoned the Ridgefield house, which was foreclosed by The Money Store in 1979. Even that caused a bit of a stir because the high bid on the place was only $120,000 — $5,000 in cash and assumption of the $115,000 mortgage. That was less than half of what the Cambridges had invested in the place, and far less than the 1979 appraisal of $160,000.

Fighting Racists and Racism

The Rev. William Webb’s first realization that American society had different things in store for white men than it did for black men came when he was in high school in New York, where he was born in 1916.

“My cousin and I were sitting around the kitchen table talking about what we wanted to be when we got out of high school,” Webb told The Ridgefield Press in 1972. “My cousin said that he wanted to be a rural postman. I said I wanted to be an accountant.

“My father, who had heard us talking, said, ‘Where have you ever seen a black accountant?’”

That incident led Webb to become more aware of the condition of African Americans around him. Frustrated at the inequities in society, he decided to end his education after graduating from high school, and look for a job.

It was 1934, the height of the Depression, and jobs weren’t easy to find. Webb wound up working on a poultry farm in Ridgefield, a black man in a community that has always been almost solely white.

“Most of the blacks then either worked in the service field or for the town,” Webb said. “There was no real middle class here. Nobody then would think of renting to black people. All were quartered in private homes.”

In the 1940s, one family — the Louis Browns, who had rented a house on southern Main Street for years — managed to buy that house from S.S. Denton; he believed that they were the first black homeowners in 20th Century Ridgefield (African Americans had owned farms here in the 18th and 19th Centuries). Webb and his wife, Delita, were said to be the third black, home-owning family when they bought their home on Knollwood Drive in 1966.

Webb said Denton also owned Bailey Avenue properties that he rented to black families, giving them a chance to live here. “It was independence in a sense; the rents were within reach of the people.”

However, racism was evident in many other cases. “One light-skinned Negro woman moved into a vacant apartment on Main Street,” Webb recalled. “Several days later, the landlord found out she wasn’t white and asked her to move out, which she did.”

There were cases of blacks’ answering ads for rents, showing up and being told the place was already rented when it wasn’t.

“It is these kinds of barriers and handicaps that can become crippling over a period of years, not to mention disheartening,” Webb said.

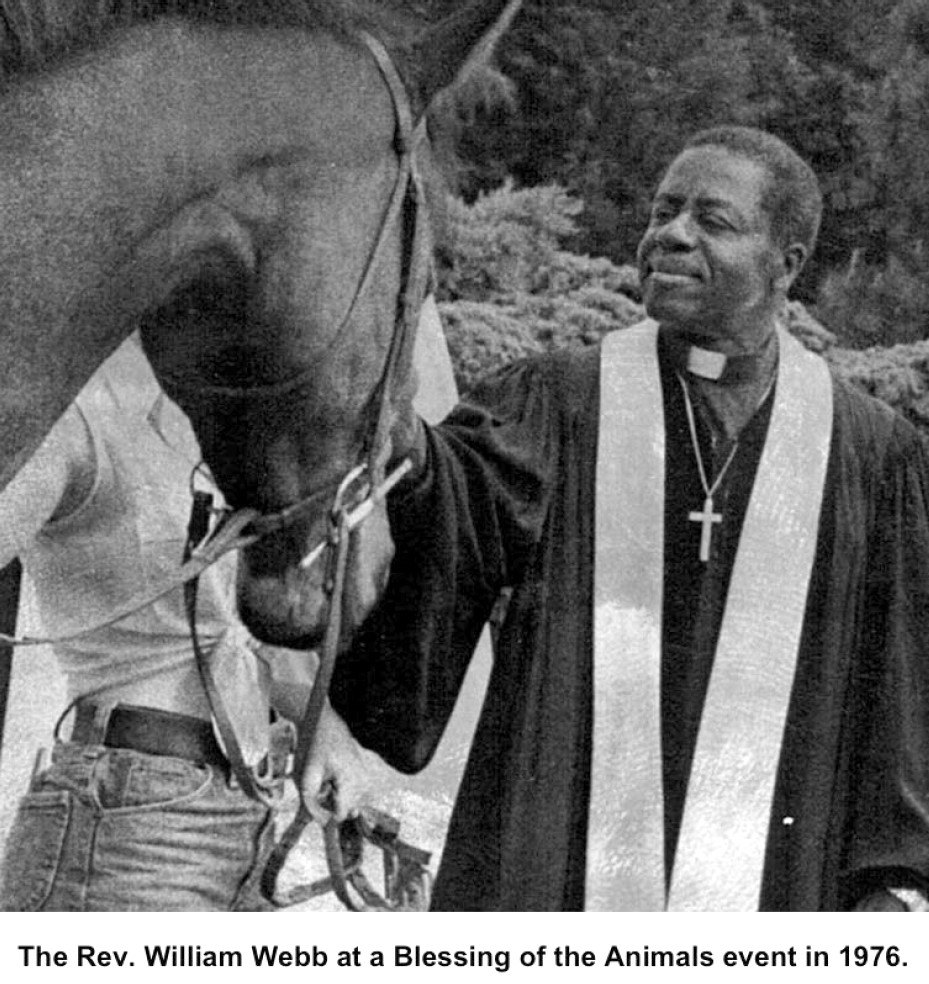

In 1951 those barriers and attitudes sparked Webb and a group of Ridgefielders, both black and white, to found the Ridgefield Branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), an organization that remained active for many years — with Webb often serving as president.

One of the NAACP’s first efforts was to seek an end to local minstrel shows in which whites comically portrayed blacks.

Advertising posters for the events, done by local school children, were very offensive to the black community.

“They depicted blacks with all the exaggerated and stereotypical black features,” Webb said. It was so bad that “black women would avoid the center of town during this time of year because of the embarrassment.”

Over the years the NAACP and Webb quietly handled cases of discrimination and abuse provoked by race. One of the saddest cases he cited involved a black man who was indirectly accused of making immoral advances to a white girl at a popular village store called Bongo’s. The charge was not made by the girl, but by a racist-minded employee of the store who saw the two laughing and conversing, Webb said. The employee filed a complaint with the police who arrested and fingerprinted the man.

Later the black man was subjected to cursing and intimidation as he’d walked to work — all for a fictitious crime, Webb said.

The case was thrown out of court.

Webb eventually became active in the state NAACP and served for a while as its president.

In 1969, he was ordained a minister, and over the years served African Methodist Episcopal congregations in Danbury, Waterbury, Bridgeport, Norwalk, and Branford, all while still living on Knollwood Road.

In Ridgefield he was also active in leading efforts to bring affordable housing to town; he often spoke at meetings to promote the need for lower-cost apartments. He served in the Ridgefield Clergy Association and on the board of directors of Danbury Hospital. A World War II veteran, he belonged to the American Legion and VFW posts.

He died in 1991 at the age of 75.

In all his handling of racial cases, William Webb said he tried to deal directly with people and not through other agents or agencies. “It’s my way of life,” he said. “I try to understand a person’s character. If I know someone’s character, then I know how to handle the matter.”

[Portions of this account appeared in Wicked Ridgefield (The History Press, 2018) and on Facebook’s “Old Ridgefield” group. They are ©2000 Jack Sanders.]