By Susan Kweskin

It’s 1792 in Ridgefield, where a wedding will soon take place. The soon-to-be bride is

Eunice Chapman Hull, born in Fairfield in the spring of 1763. Eunice will take the hand

of the twice-married Eliphalet Brush in less than three weeks… unless someone in the

community objects to their union.

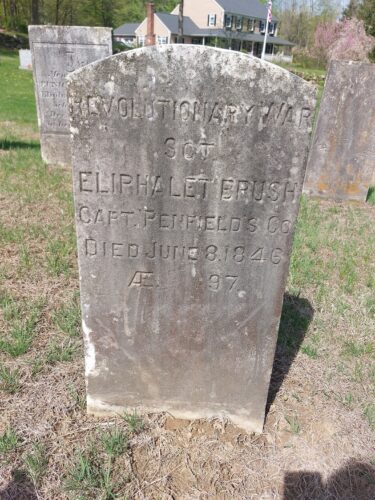

Eliphalet, born in 1749 in Ridgefield, is a desirable man. His 12 children (by the time he

stops acquiring and begetting offspring) attest to his virility. His service as a sergeant in

the Continental Army speaks to his patriotism and bravery. His role as Ridgefield’s

Assistant Assessor reflects the efficiency and economy with which he runs his

Ridgebury farm. In this official capacity, he assesses the value of his neighbors’ homes

and outbuildings, their lands, and their belongings — including their slaves. He will one

day serve Ridgefield as representative to the Connecticut state legislature.

Eliphalet’s first two wives have perished. His first bride, Hannah Hamilton, whom he wed

in 1773, died a year later at the tender age of 20. He married again in 1777 to Abigail

Dunning, who died in 1791. A year after Abigail’s passing, Eliphalet is again ready to

stand at the altar with Eunice – the widow of Seth Lee who has two children.

Where did the couple meet? And how did Eliphalet court her?

Courtship rituals in the New England of the mid-1700s weren’t what they are today.

Young couples considering marriage might “bundle” or “tarry.” (What? Walk all that

snowy way home at this hour of the night?!) Reverend Andrew Burnaby, a visitor from

England who spent a few months in New England described the practice this way:

“A very extraordinary method of courtship, which is sometimes practised amongst the

lower people of this province, and is called Tarrying, has given occasion to this

reflection. When a man is enamoured of a young woman, and wishes to marry her, he

proposes the affair to her parents, (without whose consent no marriage in this colony

can take place); if they have no objection, they allow him to tarry with her one night, in

order to make his court to her.”

At their usual time the old couple retire to bed, leaving the young ones to settle matters

as they can; who, after having sate up as long as they think proper, get into bed

together also, but without pulling off their undergarments, in order to prevent scandal. If

the parties agree, it is all very well; the banns are published, and they are married

without delay. If not, they part, and possibly never see each other again; unless, which is an accident that seldom happens, the forsaken fair-one prove pregnant, and then the

man is obliged to marry her, under pain of excommunication.”

The marriage banns Reverend Burnaby mentions are meant to ensure the orderly

celebration of marriage –- and to suss out and prevent “incestuous and other unlawful

marriages.” Betrothed couples are required to broadcast to the community their

intention to marry “in some public meeting or congregation on the Lord’s day, or on

some public fast, thanksgiving, or lecture-day, in the town, parish, or society where the

parties, or either of them do ordinarily reside” at least eight days before the ceremony

was to occur.

The twice widowed Eliphalet and Eunice probably won’t spend a night bundled up

together, but they must post their banns three times before they will be allowed to stand

before a justice of the peace. (Weddings don’t take place in churches.)

How are incestuous unions defined? The details are very specific. Note, though, that

cousins seem to be fair game.

Woe unto those who violate these rules! An unlawfully wedded couple face automatic

disinheritance of any child born to them, mandatory and prominent displaying of an

emblem on their clothing of a capital “I” for incest, even public whipping.

The rules for how the capital “I” is to be worn are clearly spelled out:

No one, apparently, has any objection to the marriage of Eunice and Eliphalet. They are

united in 1792. Was it love that led this couple to the altar? In 18 th century Connecticut,

love was not a primary consideration. Marriage was fundamental, the bedrock institution

on which social, economic, family, moral, and religious stability hinged. Adults were

expected to marry and (if necessary) remarry. Practicality and the need for a working

partnership might trump matters of the heart.

Did Eunice (or any other bride of her day) give thought to her legal rights when she

married? Married women did not then exist legally: husbands had complete legal

authority. A woman’s identity at birth came from her father; identity after marriage

became that of her husband. Everything a married woman owned became her

husband’s, including the clothes on her back. She could not own or work in a business,

and any wages she might have earned through her labor could be claimed by her

husband. There could be no contracts in her name. She had no rights to her children: if

she separated or divorced, she would have to leave her children behind. Husbands had

a legal right to sexual access – within a marriage, sexual consent was implied.

In contrast, unmarried women were legally entitled to live where they wanted and to

support themselves as long as their occupation did not require a license or college

degree. A single woman could sign contracts, own real estate, and acquire her own

personal effects.

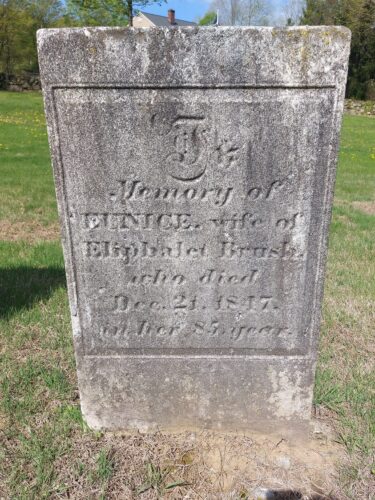

Whatever misgivings Eunice might (or might not) have had, her union with Eliphalet

proved long and fruitful, and she bore eight children, including a daughter also named

Eunice. She lived to see 1847 — a year after her husband passed at age 97. She and

Eliphalet lie near one another in Ridgebury cemetery.

*Ben Franklin had this to say about marriage: “Keep your eyes wide open before

marriage and half shut afterward.”

For more details about old-time marriage in New England, click here.