Download PDF

How to Help Future Historians

The Ridgefield Historical Society grew out of two preservation projects: the Ridgefield Preservation Trust’s Archives Committee and its Scott House committee, founded to save the 1714 David Scott House.

The Ridgefield Historical Society grew out of two preservation projects: the Ridgefield Preservation Trust’s Archives Committee and its Scott House committee, founded to save the 1714 David Scott House.

In the late 20th Century, a dedicated group had been collecting and/or copying documents and photographs that tell Ridgefield’s story. The goal was to protect as much as possible before items were lost – discarded or dispersed to collectors. Many of these preservation-minded people became the core of the Scott House committee and eventually of the new RIdgefield Historical Society.

When the rebuilt David Scott House opened, it became the repository for all the Archives Committee’s work, installed in the climate-controlled vault that formed the basement of the building. The collection has expanded greatly thanks to acquisitions and donations over the 20 years since the historical society took up residence at 4 Sunset Lane. The Warren Arthur Architectural Archives have added a dedicated space to preserve the work of architects who’ve made their mark on Ridgefield. All accessions are assessed, identified and entered into the Past Perfect digital cataloging system, making them accessible to online searches.

Worth saving?

Some may wonder if what they have is of sufficient value to be added to the collection.

We asked Jack Sanders, who has been a student of Ridgefield history since he joined the Ridgefield Press staff in 1967 and is a frequent donor of materials to the historical society: What should people think about saving for future historians? The author of eight published Ridgefield histories, he has four more in the works, in addition to the daily doses of Ridgefield’s past that he publishes for the Old Ridgefield Facebook group and the ridgefieldhistory.com website that he maintains (much of his work is also available at ridgefieldhistoricalsociety.org).

Sanders’ response:

“Many pieces of ephemera — mostly paper publications and hand-written records — provide clues about how people lived and thought at any given time. While much of the more important happenings in society are recorded in many publications, it is the close-to-home, everyday activities and conversations of individuals that are often less documented and that help provide a more accurate look at the past.”

One of his early forays into historical research was a series that ran in The Ridgefield Press in the 1970s, based on the 1865-1866 diary of a farmer who lived on Silver Spring Road. The simple, brief daily record, extensively annotated by Sanders, showed the daily patterns and interactions of a subsistence farmer and shoemaker in the mid-19th Century. (The Diary of Jared Nash is available on Sanders’ website, the Ridgefield Historical Society website and at the Scott House library.)

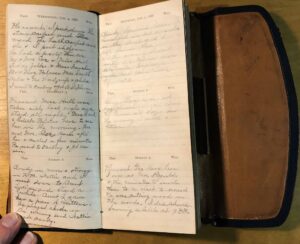

Recently Sanders has annotated another diary (image above), from 1888, by another Ridgefield farmer, Gilbert Birdsall Burr, born in 1866. A generation removed from Jared Nash, he lived on Ridgebury Road and was long active in town affairs. Gilbert Burr’s diary was posted during 2022 and is available on the Old Ridgefield Facebook group.

Finding a Ridgefielder’s diary is fairly rare, but what’s preserved now will be the detail that informs the work of later historians. The historical society’s archives include several diaries, among them the year recorded by Frederic Remington as he was building and moving into his home here.

Here are items that Sanders recommends saving:

- Photographs of people, places and events, with the date they were taken and the contents — as much as possible — identified, especially people.

- Birth, marriage, death certificates, cemetery records, bills of sale, deeds, surveys, and other legal documents, especially those that may not be found in a town hall or court.

- Letters and postcards that tell about events or experiences that may be of interest to future generations, especially reminiscences of the past.

- Maps, including community maps, property maps, neighborhood and business district maps.

- Business guides, such as community shopping guides, showing where the businesses were and what they specialized in.

- Programs from local events, such as high school theatrical productions, awards presentations, celebrations, benefits, fairs, local concerts, testimonial dinners — especially if they list the names of participants and/or biographical information.

- Newspaper/magazine clippings that tell about local people and places. Always make sure they are dated and note the source.

- Diaries that reflect the daily life of an individual.

- Scrapbooks that focus on people, places, and events.

- School yearbooks from any level.

- Instruction manuals for devices of the past such as land-line telephones, tape recorders, old automobiles, toys (Erector sets, science kits, trains, etc.)

- Job descriptions.

- Family recipe collections that reflect period tastes and food products.

- Audio and video recordings of memories of past events, including tapes and movies (which can be digitized).

- Unpublished historical papers, including family genealogies and histories.

The Ridgefield Historical Society actively collects such materials and invites prospective donors to contact us for more information: [email protected] or 203-438-5821.

Whose wood was it? A judgment rendered in 1925

Legal documents in the Ridgefield Historical Society archives are often records of commonplace events: property transfers, mortgage deeds, organizational documents. There’s a story in each of them, although it may not always be easy to flesh out the details of a particular transaction, or the people involved.

Legal documents in the Ridgefield Historical Society archives are often records of commonplace events: property transfers, mortgage deeds, organizational documents. There’s a story in each of them, although it may not always be easy to flesh out the details of a particular transaction, or the people involved.

A family collection of legal papers given to the historical society some years ago had, mixed in with a stack of deeds, a March 17, 1925 three-page memorandum of decision from the Fairfield County Court of Common Pleas that told an interesting story of justice, delayed but finally achieved. Judge Frederick Huxford, ruling for plaintiff Louie Remowaldo, ordered Mary Knapp to pay Mr. Remowaldo $230.61. That was a large sum in 1925, the equivalent of about $3700 today.

The payment to Mr. Remowaldo was to cover the costs he incurred when Ms. Knapp accused him of theft, telling authorities that he had cut wood from property she owned. In the judgment of the court, he hadn’t, and she had accused him falsely.

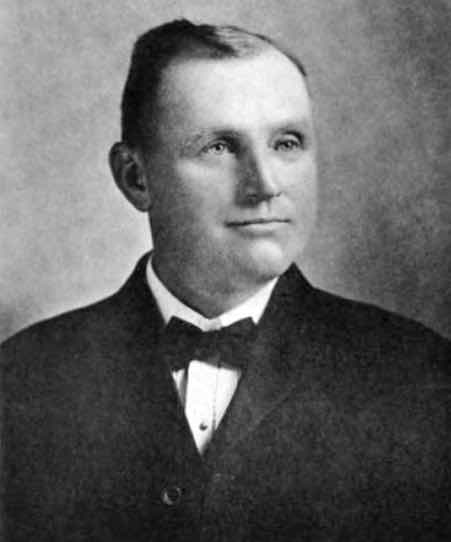

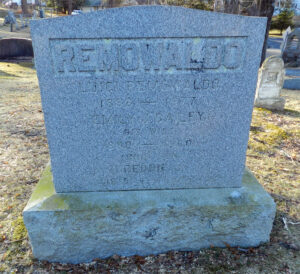

One of Ridgefield’s earliest Italian residents, Luigi Remowaldo arrived here in 1911 and soon was working at H.B. Anderson’s Port of Missing Men resort. As recorded in Aldo Biagiotti’s history, IMPACT: The Historical Account of the Italian Immigrants of Ridgefield, Connecticut, “Luigi Remowaldo was born on January 26, 1888, in Fiumana, Province of Forli, Italy.” Mr. Remowaldo’s grandson, Peter Green, told Mr. Biagiotti: “My grandfather’s last name has been spelled in different ways.” An Italian passport, dated September 30, 1910, reflects the last name as Romoaldi. An Italian penal certificate (required for emigration) dated February 18, 1911, has the name Romualdi. An Italian Republican Party membership booklet, dated January 29, 1913, has the last name as Rimuvaldi. The IAMAS (Italian American Mutual Aid Society) membership booklet, dated May 10, 1934, has the name as Rimuovaldi. The last word on his name is at Fairlawn Cemetery where his name is carved in granite as Luigi Remowaldo.

One of Ridgefield’s earliest Italian residents, Luigi Remowaldo arrived here in 1911 and soon was working at H.B. Anderson’s Port of Missing Men resort. As recorded in Aldo Biagiotti’s history, IMPACT: The Historical Account of the Italian Immigrants of Ridgefield, Connecticut, “Luigi Remowaldo was born on January 26, 1888, in Fiumana, Province of Forli, Italy.” Mr. Remowaldo’s grandson, Peter Green, told Mr. Biagiotti: “My grandfather’s last name has been spelled in different ways.” An Italian passport, dated September 30, 1910, reflects the last name as Romoaldi. An Italian penal certificate (required for emigration) dated February 18, 1911, has the name Romualdi. An Italian Republican Party membership booklet, dated January 29, 1913, has the last name as Rimuvaldi. The IAMAS (Italian American Mutual Aid Society) membership booklet, dated May 10, 1934, has the name as Rimuovaldi. The last word on his name is at Fairlawn Cemetery where his name is carved in granite as Luigi Remowaldo.

After returning to Italy to serve in the Italian Army in 1913, Mr. Remowaldo came back to Ridgefield where he married Emily Bailey and worked on a private estate.

In 1925, when he was arrested on the charge of theft, Mr. Remowaldo was brought before the Justice Court in Ridgefield. However, the case was not prosecuted: “Case withdrawn by request of Grand Juror,” noted Judge Huxford.

In Judge Huxford’s March 17, 1925 decision ordering Mrs. Knapp to pay damages, the judge, a graduate of Yale University and Harvard Law School, laid out his legal (and lengthy) route to reach that conclusion. “The evidence… fairly supports the reasonable conclusion that there was want of probable cause, whereby the defendant was not legally justified in her action of reporting to the Grand Juror and thereby putting criminal processes of the law in motion against the plaintiff through him.

“If the defendant believed — and here assuming for our present purposes, only, that she did believe it to be true and that she actually entertained the belief — that she owned the cut wood because she held title to the land from which the trees grew from which the wood was had, such belief on her part was founded upon circumstances, the evidence discloses and establishes, which made the belief not a reasonable one, and so, too, what appeared to the defendant to be true in respect to her title to and ownership of the land, trees and wood — if it did so appear to her to be true — she was not justified in entertaining and believing it to be such since, though those appearances might have been prima facie sufficient to support a belief that she was possessed of title and ownership, yet, in the light of the knowledge or lack of knowledge she possessed upon those things, she knew, or, as a reasonably prudent and careful person, she should have known that the appearances might be different in reality from what they seemed to be upon their surface. [Editor’s Note: A 189-word sentence by the Judge!]

“Since probable cause did not exist for the charge against the plaintiff, upon which he was arrested and prosecuted in the Justice Court, at the defendant’s instigation and in which she personally participated, the law will imply maliciousness on the part of the defendant, even if express malice shall be wanting and was not shown on the defendant’s part.

“Want of probable cause and legal malice having been proven by the plaintiff, he is entitled to recover damages from the defendant.”

Judge Huxford totaled up the damages from the false arrest: $25 for counsel’s retainer, $15 for professional services of his attorney, $4 for taxi hire, three days’ lost wages at $3.87 per day, for $11.61; in all, $55.61. In addition, the judge added on costs for the current case, although no request for specific compensation had been made: “However, in this instance, under such circumstances, it is permissible for the trier to award a reasonable amount to the same. Judgment, therefore, is rendered for the plaintiff to recover $230.61 and his costs.”

It was a sad decade for both Mary Knapp, recently widowed, and for Luigi Remowaldo, whose six-year-old son Freddie, died in 1925. They both lived for many years on West Mountain: she died in 1973 at 94 and he died in 1977 at 89. They are buried not far from each other, she in Maple Shade Cemetery and he in Fairlawn Cemetery.

The Scott House Journal (SHJ) is a quarterly publication, sharing stories of Ridgefield past. It is written by Sally Sanders, Historical Society Board member and former arts editor